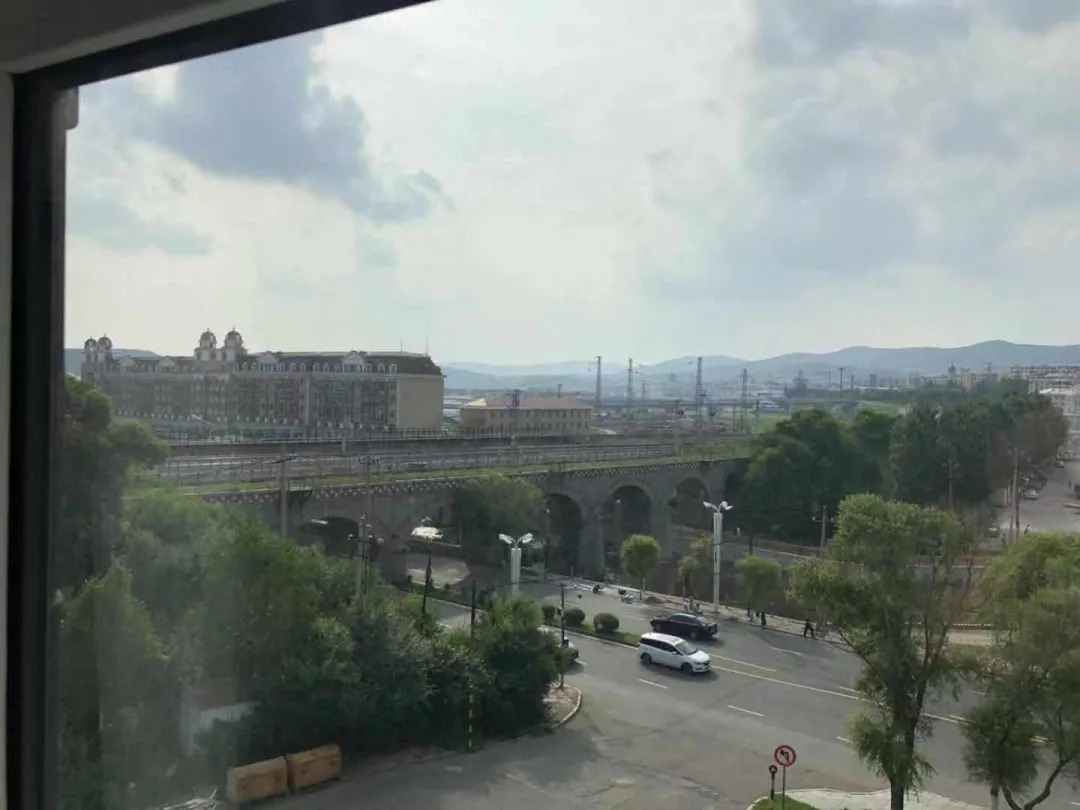

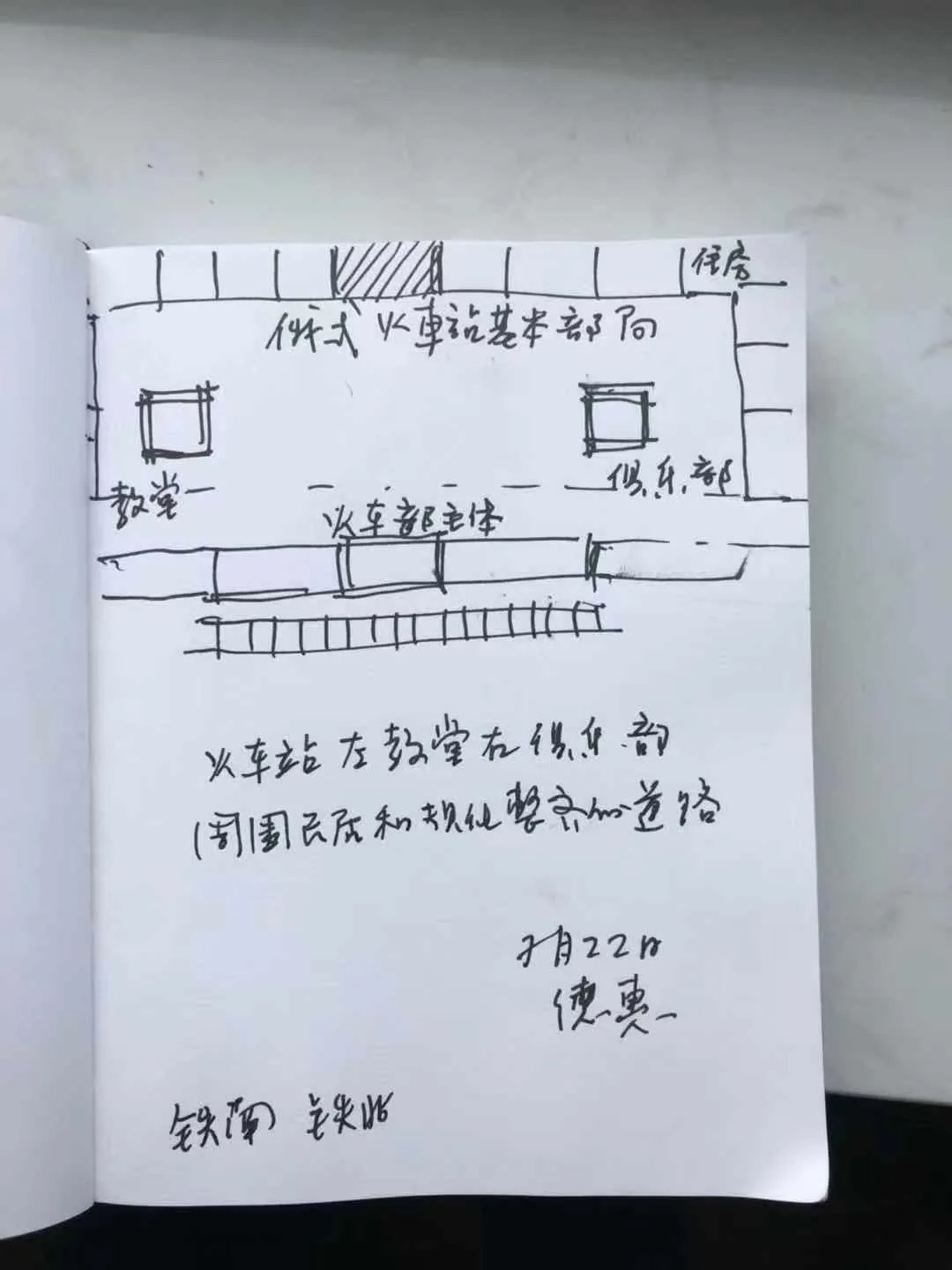

Born in Qiqihar, Zhang Hui grew up with the railways. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the railways would take on a very different significance than what they held at the beginning of the 20th century. The railways symbolised productivity and progress built by the hands of the proletariat. On his journey from Lvshun to Harbin, Zhang Hui passed through the stations at Dalian, Anshan, Haicheng, Shenyang, Sujiatun, Siping, Dehui and other stops and headed further east towards Hengdaohezi, Mudanjiang and Suifenhe. At all the stops along the way, the construction and history of the railways and the railways’ impact on socio-cultural constructs were to focus of his attention.

Faced with the architectural sites along the southern branch of the China Eastern Railway (the South Manchuria Railway), Zhang Hui noted that the railway expresses “a sort of strategy, built upon a variety of self-administered, nearly complete systems which in the arrival of reality and a yearning for the future flattened out all sorts of detailed differences; in standardising propriety and scale and in the pursuit of a commonality that still retains difference, the architecture and private houses along the South Manchuria Railway retain a foreign flavour of the political strategies of worldbuilding.”

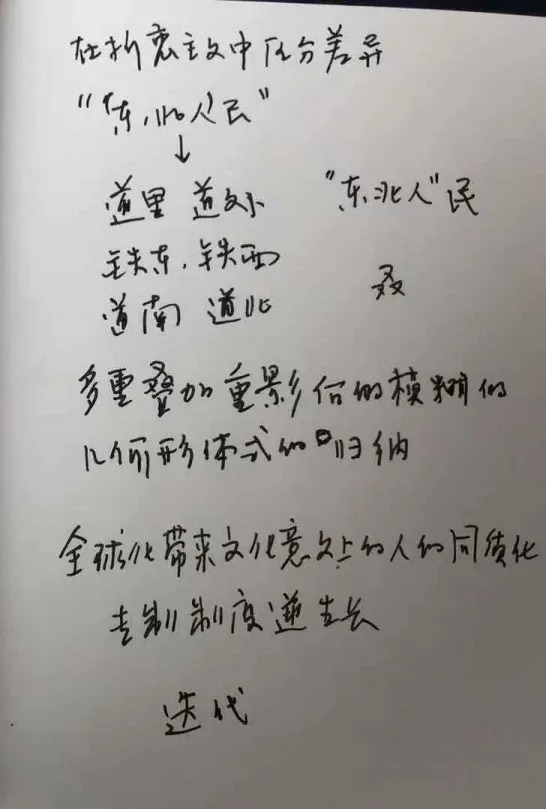

The eclecticism of South Manchuria during that time period created an amalgam of different architectural styles. Just as the region had to face the reality of ethnic complexity, Zhang Hui has a keen intuition for the kineticism behind such excavations of worldbuilding. After the founding of the People’s Republic, for those people who moved to Harbin and its surroundings from the rest of China to carry out construction work, their identity as people from “Dongbei” would always be placed above their previous identity that remained at their core and could never supplant it. The work they were involved with on the railways or in heavy industry likewise would take on a lofty, almost utopian colour of national idealism. As Zhang Hui remarked during the trip, “I particularly cherish Dongbei, because it is unadulterated by [China’s] five-thousand year history, representing a sort of ‘blank space’”.

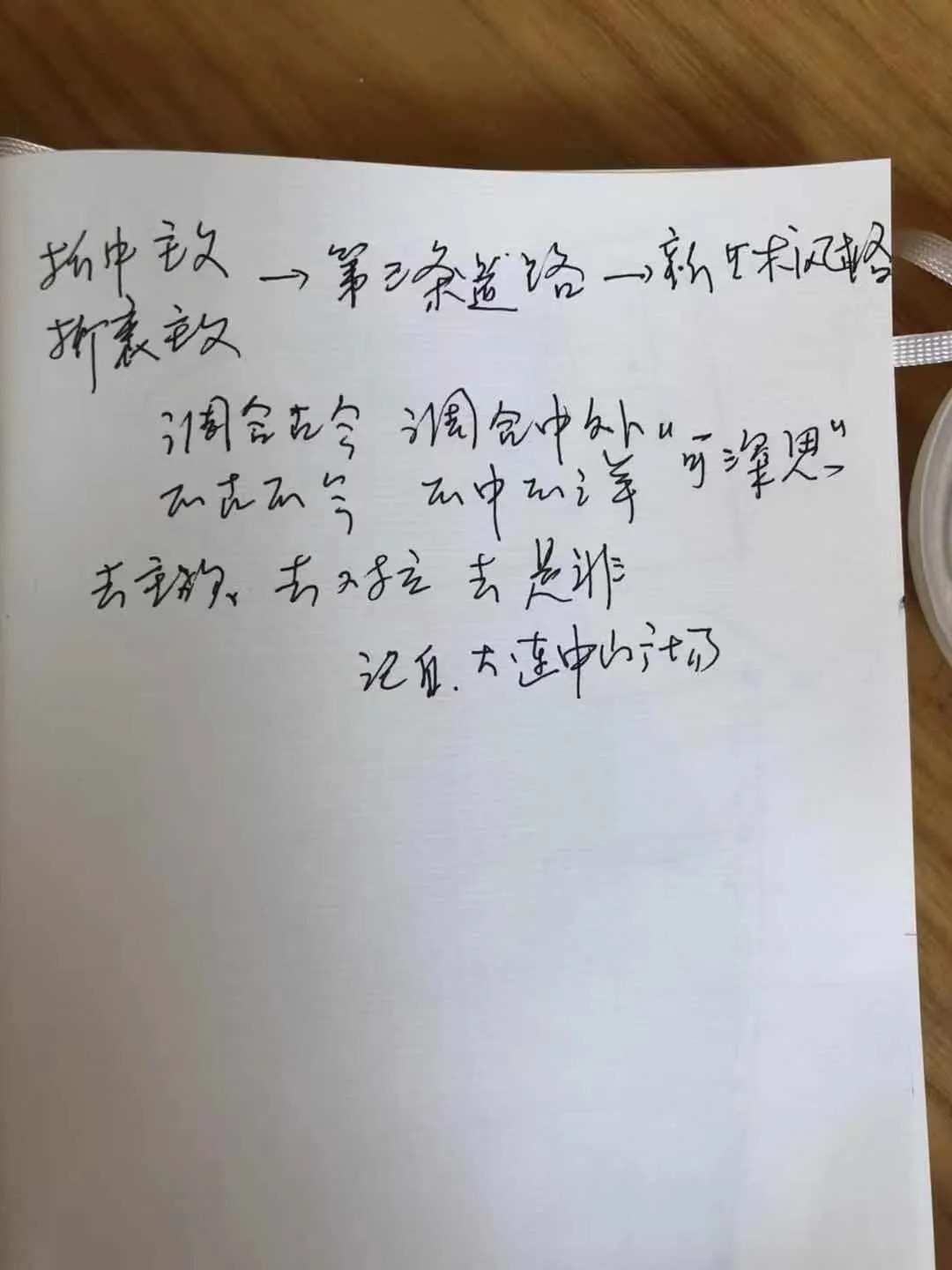

“I had a plan to complete ‘Space’, ‘Object in Space’ to ‘Person in Space’ by the year before last. For these three big pieces of work, I used painting to construct my own visual structure, the past decade or so of my work forming a sort of ‘rudimentary science’. What I now wish to narrate is how to combine space, object, and human figures in the space of one painting. Returning to the current questions brought up by the China Eastern Railway, I would call it an overlapping of imagery, a mutual construction and interaction giving birth to a sense of spatial disjointedness; complex information becoming an indistinct realm, which originally was nothing but blank space. How will a person transform when placed within such a seemingly chemically-prepared space, where is the subjectivity? I come to realise how my relationship to the China Eastern Railway, to my hometown in Dongbei, to my father’s career comes to be placed within such a plane. I come to wonder about how behind this sort of indistinct overlapping imagery and multiplicity of relationships, a person or an object can construct a sufficiently powerful space.”