Long March Project – Chinatown

Yokohama Chinatown | Yokohama Triennial

Chinatown

Time: November 5 – May 8, 2005

Location: Yokohama

Participating Artists: Chen Xiaoyun, Yao Jui-Chung, Jiang Jie, Long March Collective (Guo Fengyi, Hu Xiancheng, Qiu Zhijie, Xu Zhen, Zhao Gang, and an anonymous artist)

San Francisco Chinatown | Curating Contemporary Art, California College of Art

Chinatown

Time: November, 2005

Location: San Francisco

Auckland (No) Chinatown | Auckland Triennial

Chinatown

Time: March 9 – June 3, 2007

Location: Auckland

Yokohama Chinatown | Yokohama Triennial

Chinatown

Time: November 5 – May 8, 2005

Location: Yokohama

Participating Artists: Chen Xiaoyun, Yao Jui-Chung, Jiang Jie, Long March Collective (Guo Fengyi, Hu Xiancheng, Qiu Zhijie, Xu Zhen, Zhao Gang, and an anonymous artist)

The Yokohama Chinatown was first established during the Chinese Ming Dynasty (1871). Over 100 years since its establishment, Chinatown has developed from relying on the businesses of the "three knives" (hair-clippers, chef’s knife, and tailor’s scissors), to today where there exists a well developed and independent economic culture and social system.

In this context, "nostalgia" has been converted into a reciprocal experience and strategy. Within this self-recognized world, how do we use the vision and method of culture to deconstruct and distinguish between those spiritual/psychological spaces that either exist, have been extinguished, or completely altered, and the space left between the individual cultural discrepancies and the collective subconscious memory? How is all of this being covered and symbolized in the "ordinary"?

Because of the relationship the history of Yokohama has with today’s social and political-economic conditions and Chinatown, the Yokohama Triennial presented an ideal context to realize "Long March – Chinatown". The Long March Collective included 6 Chinese artists, who each produced works in collaboration with Long March. Production of the works created a connection between the exhibition space and Chinatown. A portion of the works were carried out in Chinatown spaces, creating a relationship with the art audience and the people on the streets of Chinatown that lies somewhere between art and ordinary life. The Long March team also conducted a survey at numerous venues in both the triennial space and Chinatown.

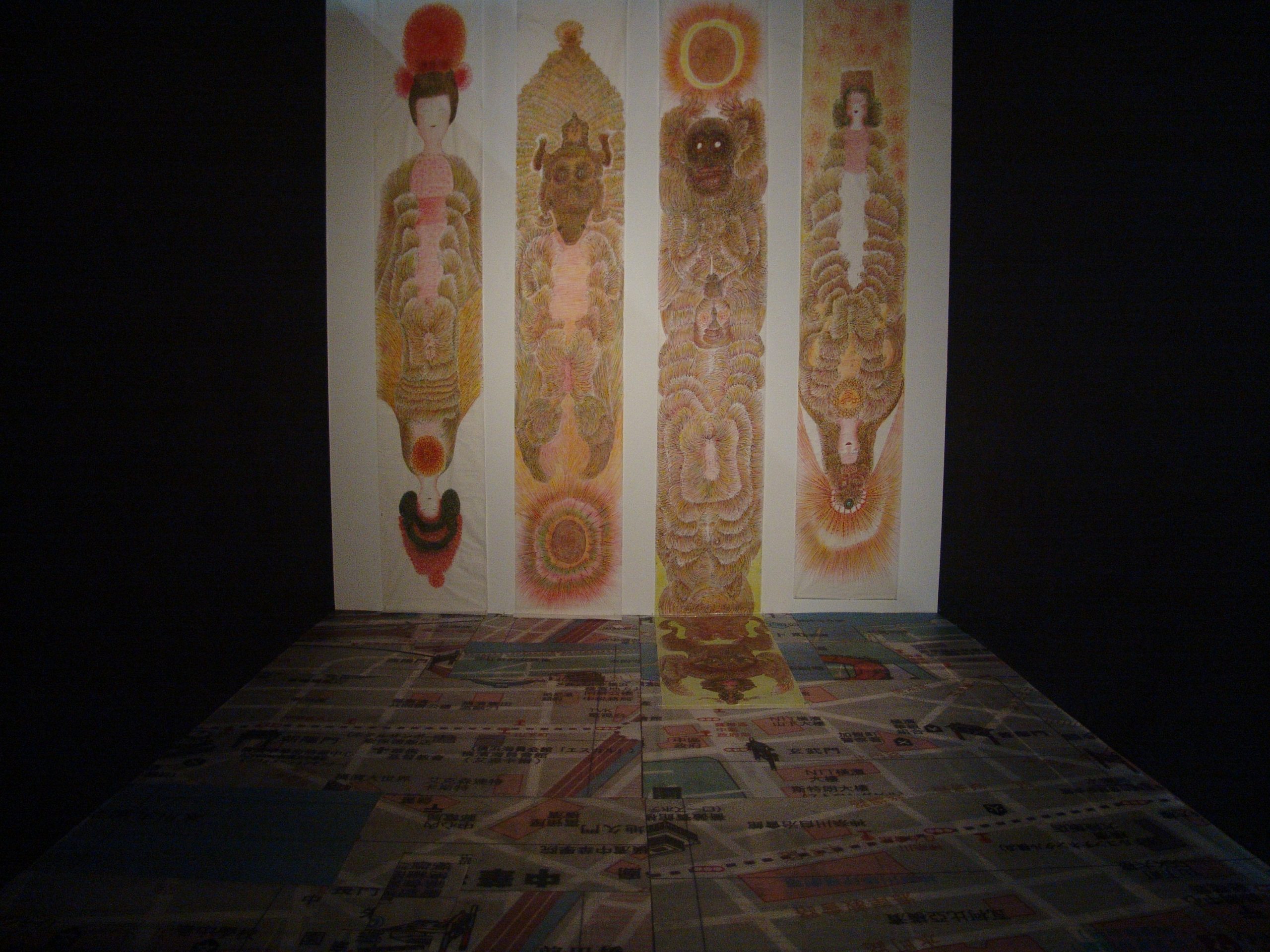

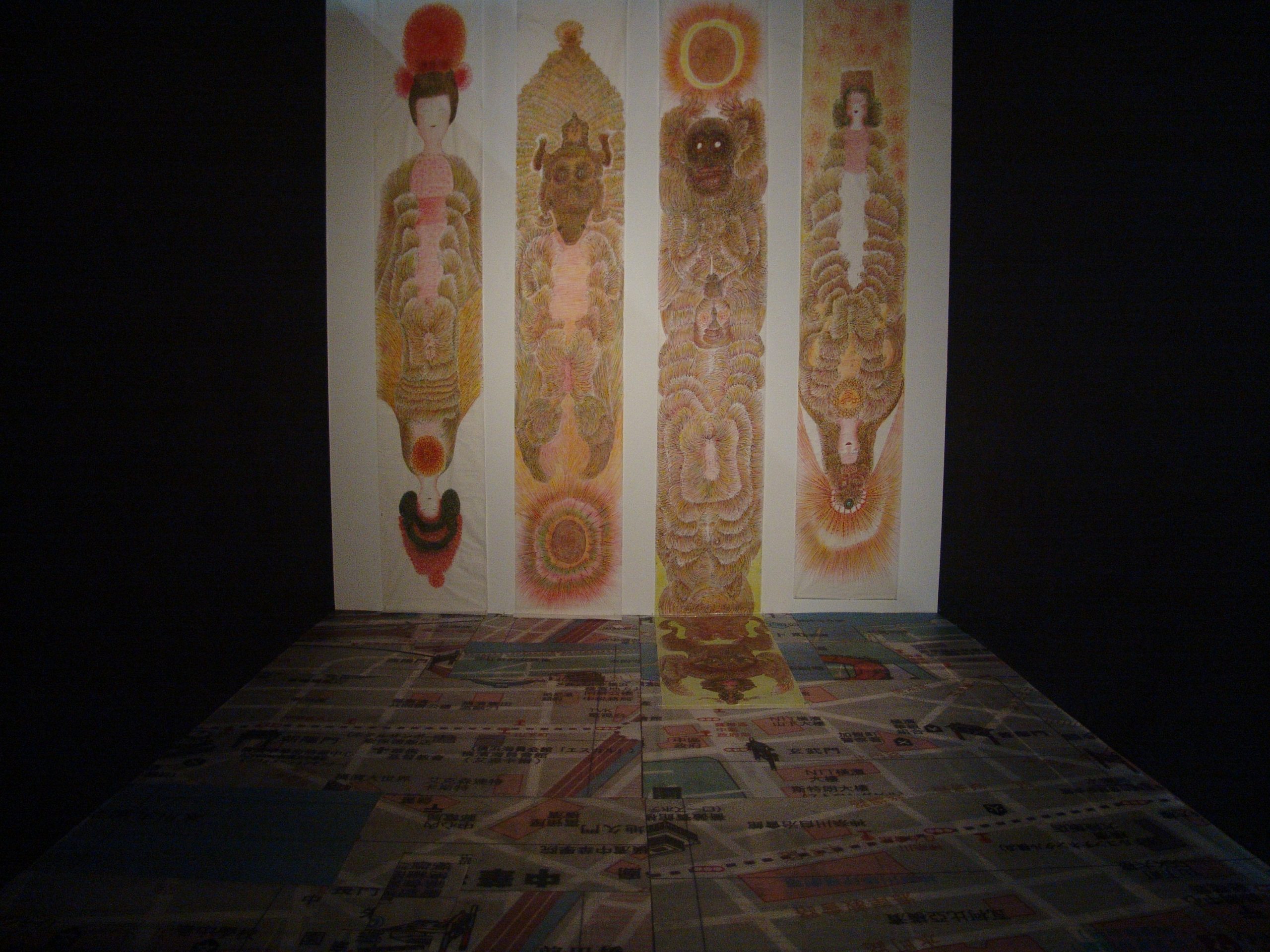

Guo Fengyi

Guo Fengyi, Chinatown, painting and performance, 2005

Guo Fengyi, a 63-year-old woman artist with psychic powers, is presenting a drawing performance. Her work is informed by the concept of the Tao (The Way), a worldview that originated in ancient China. Taoism, which appears in overseas Chinese societies throughout the world, has become a symbol of a universal philosophy of life as well as the religion of a particular ethnic group. This work is not just a Taoist experiment but an exploration of different places in China and Japan. Which are both under the influence of the same philosophy.

Hu Xiangcheng

Hu Xiangcheng, Building Code Violations, 2005

Building Code Violations questions the concept of violation and the reasonableness of what is considered correct or standard. What is correct? Who determines the standard? Many buildings that are in violation of building codes can be found in China because of changes made under policies of reform or liberation. The concept of violation includes such meanings as temporary, portable and evasive. It represents everyday resistance to the administrative and legal system. If Chinatowns are imaginary constructs in relation to the real China, we might see the superficial Western appearance of many large buildings being constructed in China today as the prototype of another kind of Chinatown.

Jiang Jie

Jiang Jie, Swimming Dragon, 2005

Swimming Dragon looks like the roof of a Chinese-style building, floating in the exhibition space, but also has the appearance of a moving dragon. Visitors are allowed to take home pieces of tile from the roof, and it eventually disappears as the tiles are removed one by one. The artist chose the image of the dragon as a symbol of the Chinese people, suggesting the underlying reality of volatile cultural and political movements taking place beneath the façade of a traditional Chinese building. As this work is deconstructed by the audience, a new structure will be constructed and eventually materialize next to it. In a work that invites the participation of the viewer, Jiang looks at cultural history and human survival with a sense of humor. The simultaneous deconstruction and construction and shift from one place to another suggest the rejection of narrow ethnic nationalism and lead up to the context of the Chinatown Project.

Xu Zhen

Xu Zhen, 8848, 2005

Xu Zhen’s 8848 is an installation that contains a false documentary video showing the process of carving out the Himalayas as well as fake documents and equipment related to this non-existent project. Xu questions the concept of “the facts”, ironically suggesting that “everything is play-acting,” and the idea of a “universal perception” common to all human beings is false. This also applies to the “facts” that appear in discussions of “transplanted Chinatowns.” Xu’s work explores misreading of Chinese history and their relationship to places of transplanted history, that is, Chinatown. It is an ironic narrative that comments on ambition, personal desire, and the blind pursuit of betterment of the human race, all causes of political, economic, cultural and historical breakdown in today’s world.

Qiu Zhijie

Qiu Zhijie, Slowly Approaching, 2005

It’s a performance and installation based on the lion dance, a traditional performance based on myths from the Tang Dynasty, which is held on festival days to ward off evil. The artist thinks of the relationship between the elements of “hiding-camouflage”, “play-lion dance”, “performance-Chinatown”, and “display-main exhibition hall” as corresponding to actual problems of ethnic culture. The condition of motion in this work alludes to the “Long March of Chinese culture.” Through his actions, Qiu metaphorically expresses the gap between geopolitics and the migration of cultures as well as the conflicts within the same culture. The performance of the lion dance, carried out in Chinatown and the exhibition hall, is one of the most familiar aspects of Chinese celebrations in China. It will add a festive note to the triennial.

Xu Zhen, 8848, 2005

Xu Zhen’s 8848 is an installation that contains a false documentary video showing the process of carving out the Himalayas as well as fake documents and equipment related to this non-existent project. Xu questions the concept of “the facts”, ironically suggesting that “everything is play-acting,” and the idea of a “universal perception” common to all human beings is false. This also applies to the “facts” that appear in discussions of “transplanted Chinatowns.” Xu’s work explores misreading of Chinese history and their relationship to places of transplanted history, that is, Chinatown. It is an ironic narrative that comments on ambition, personal desire, and the blind pursuit of betterment of the human race, all causes of political, economic, cultural and historical breakdown in today’s world.

Yao Jui-chung

Yao Jui-Chung, The World is For All––China beyond China, 1997

“The World Is For All” is an installation that Yao Jui-Chung has been creating since 1997 featuring images of Chinatowns throughout the world. The artist believes that this phrase, the idealistic slogan of nation-building propounded by Sun Yat-sen, founder of Chinese republic, can be applied to today’s Chinatowns. Chinatowns are special sites, where the historical memories of immigrants are mixed with the cultural characteristics of each location. They are places where people of Chinese origin are at a distance from their native country but also create a boundary bewteen themselves and the place where they live their everyday lives. In this complex social situation, marked by mutual interaction, the inhabitants are engaged in an ambivalent struggle with the problems of their own identity and how to relate to global and local influences.

Chen Xiaoyun

Chen Xiaoyun, Several Moments Extending to a Night, video, 2004

Images here are just some temporary fragments, which are extending to the night or being extended by the night. Turning over the cellar of your memory; climbing up the attic of your unconsciousness; walking into the back garden of your dream; moving over the flagstone of the mouth of your daydream well. Suppose that there are many ways to enter into a night and the entrance to time can be extended by sensation, then time would be just a gift that images contribute to feelings. The scenes in a mass, the obscure tone, the kid show and the mechanical banters, all of them are folded together at the moment when the night is coming. It looks like that there is a horizon waiting for numberless moving scenes.

Zhao Gang

Zhao Gang, The Harlem School of Socialist Realism Study, 2002

The project was initiated by Chinese-American artist Zhao Gang, as a casual discussion around his dinner table in Harlem. Key local African American and Chinese artists and thinkers took part – Satch Hoyt, Franklin Sirmans, Deborah Grant, Lilly Wei, Brett Cook-Dizney and Jeff Sonhouse. They considered the possibility of a New Social Realism, debating the facts and philosophical similarities surrounding the genesis, influences and motivations of revolutionary acts in Chinese and African American society, and the broader global arena.

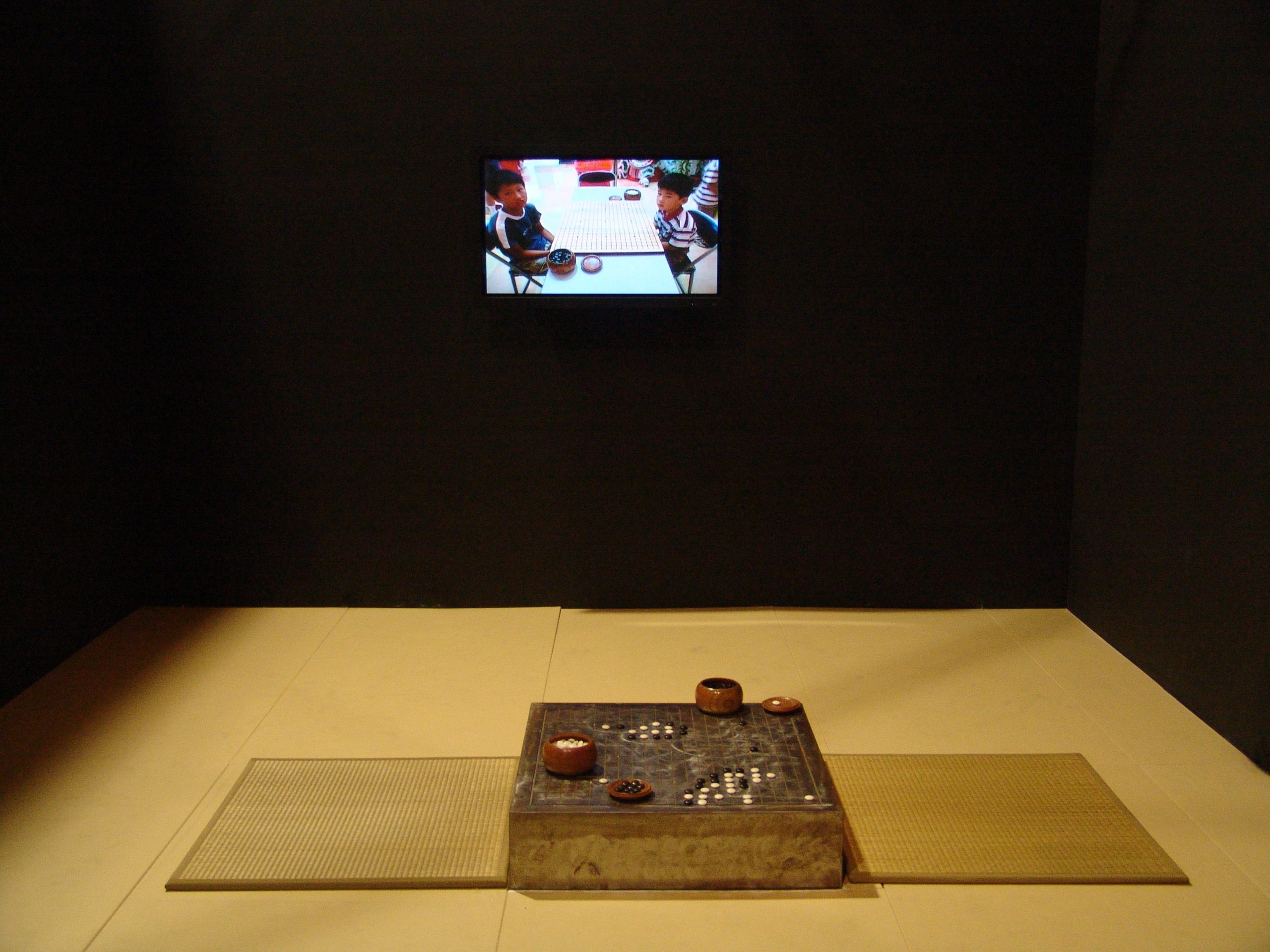

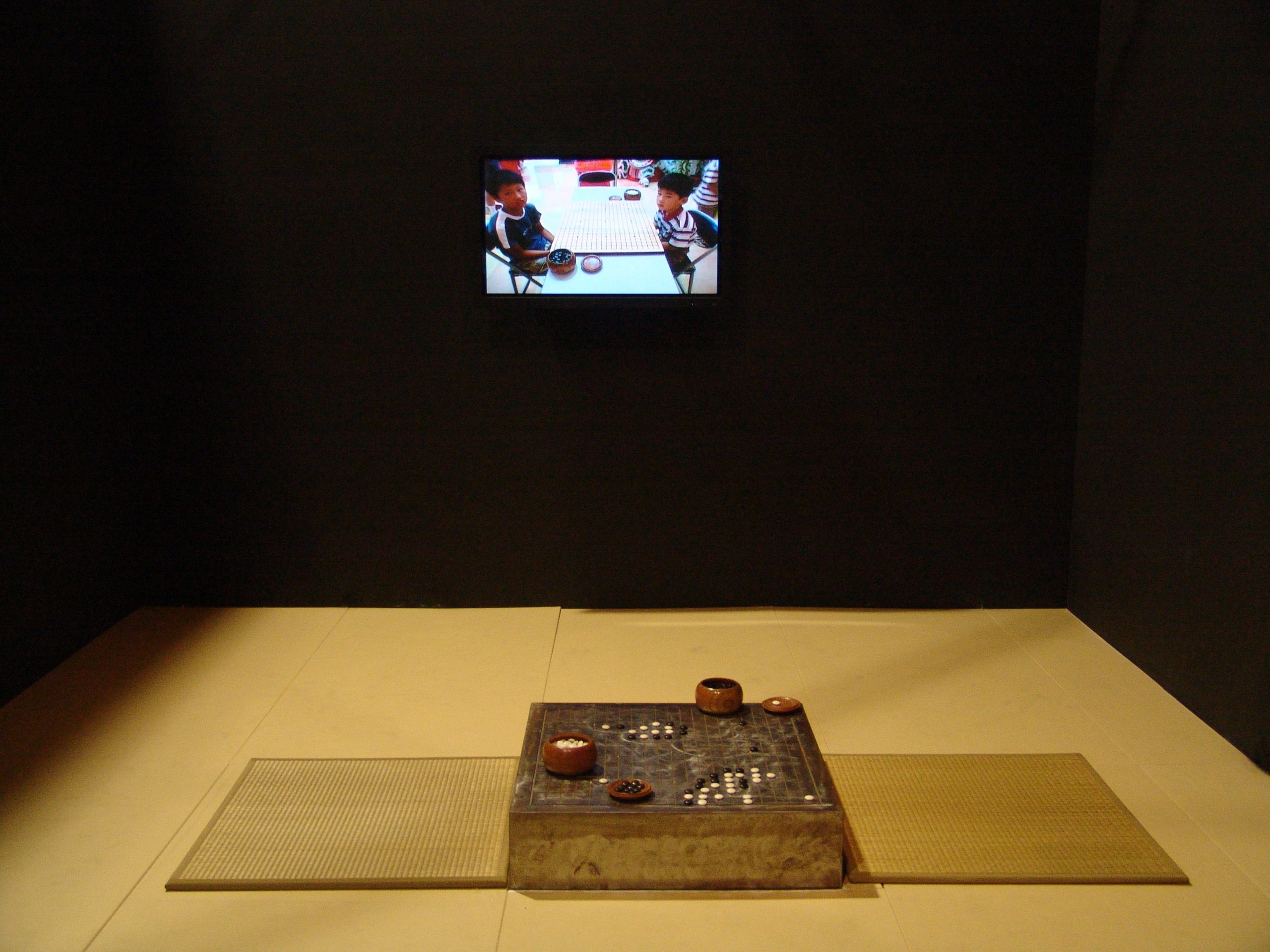

Anonymous Artist

Anonymous, 21 Go, 2005.

The artist is one who was considered very active in China in the late 1980s but moved to a life in seclusion in a southern Chinese city where they keep a low-key lifestyle and devote themselves to the study of the game of Go.

The game of Go was spread from China to Japan during the Northern and Southern Song period, with the exchange of game tactics and skills between the two countries taking place in the 13th century. The majority of the game’s current players are to be found in Mainland China, Japan, and Taiwan. A number of today’s Go masters are from Taiwan but were taught and/or brought up in Japan; Go is a cultural resource shared by the three regions and is a node of interaction and influence among their histories, cultures, and economies. 21 Go presents a solution of cultural significance to the tensions inherent in the current global geopolitical structure. The creativity of the piece resides in “making another way” (real Go boards are composed of a square grid of 19 lines), and in the utility of the political implications inherent in a “strategy” of “game theory” behaviour. The artist takes a seemingly light-hearted game and uses is to describe the sensitivities and frustrations in the current state of coexistence and contradiction that suffuses Asia’s current political and economic reality, and the potential collusion of interests between the three regions; a “game theory” of an unending break with tradition and conventional awareness.

The execution of this work is formed of two parts: The plan calls for one part (a game or broadcast) in the main exhibition space, the other part (a game or broadcast) will be carried out in Chinatown. Young Go players from Mainland China, Japan and Taiwan will play the game, and the process will be exhibited at the different sites by means of a live video feed.

The artist has decided to hide their name and identity in this work.

The Yokohama Chinatown was first established during the Chinese Ming Dynasty (1871). Over 100 years since its establishment, Chinatown has developed from relying on the businesses of the "three knives" (hair-clippers, chef’s knife, and tailor’s scissors), to today where there exists a well developed and independent economic culture and social system.

In this context, "nostalgia" has been converted into a reciprocal experience and strategy. Within this self-recognized world, how do we use the vision and method of culture to deconstruct and distinguish between those spiritual/psychological spaces that either exist, have been extinguished, or completely altered, and the space left between the individual cultural discrepancies and the collective subconscious memory? How is all of this being covered and symbolized in the "ordinary"?

Because of the relationship the history of Yokohama has with today’s social and political-economic conditions and Chinatown, the Yokohama Triennial presented an ideal context to realize "Long March – Chinatown". The Long March Collective included 6 Chinese artists, who each produced works in collaboration with Long March. Production of the works created a connection between the exhibition space and Chinatown. A portion of the works were carried out in Chinatown spaces, creating a relationship with the art audience and the people on the streets of Chinatown that lies somewhere between art and ordinary life. The Long March team also conducted a survey at numerous venues in both the triennial space and Chinatown.

Guo Fengyi

Guo Fengyi, Chinatown, painting and performance, 2005

Guo Fengyi, a 63-year-old woman artist with psychic powers, is presenting a drawing performance. Her work is informed by the concept of the Tao (The Way), a worldview that originated in ancient China. Taoism, which appears in overseas Chinese societies throughout the world, has become a symbol of a universal philosophy of life as well as the religion of a particular ethnic group. This work is not just a Taoist experiment but an exploration of different places in China and Japan. Which are both under the influence of the same philosophy.

Hu Xiangcheng

Hu Xiangcheng, Building Code Violations, 2005

Building Code Violations questions the concept of violation and the reasonableness of what is considered correct or standard. What is correct? Who determines the standard? Many buildings that are in violation of building codes can be found in China because of changes made under policies of reform or liberation. The concept of violation includes such meanings as temporary, portable and evasive. It represents everyday resistance to the administrative and legal system. If Chinatowns are imaginary constructs in relation to the real China, we might see the superficial Western appearance of many large buildings being constructed in China today as the prototype of another kind of Chinatown.

Jiang Jie

Jiang Jie, Swimming Dragon, 2005

Swimming Dragon looks like the roof of a Chinese-style building, floating in the exhibition space, but also has the appearance of a moving dragon. Visitors are allowed to take home pieces of tile from the roof, and it eventually disappears as the tiles are removed one by one. The artist chose the image of the dragon as a symbol of the Chinese people, suggesting the underlying reality of volatile cultural and political movements taking place beneath the façade of a traditional Chinese building. As this work is deconstructed by the audience, a new structure will be constructed and eventually materialize next to it. In a work that invites the participation of the viewer, Jiang looks at cultural history and human survival with a sense of humor. The simultaneous deconstruction and construction and shift from one place to another suggest the rejection of narrow ethnic nationalism and lead up to the context of the Chinatown Project.

Xu Zhen

Xu Zhen, 8848, 2005

Xu Zhen’s 8848 is an installation that contains a false documentary video showing the process of carving out the Himalayas as well as fake documents and equipment related to this non-existent project. Xu questions the concept of “the facts”, ironically suggesting that “everything is play-acting,” and the idea of a “universal perception” common to all human beings is false. This also applies to the “facts” that appear in discussions of “transplanted Chinatowns.” Xu’s work explores misreading of Chinese history and their relationship to places of transplanted history, that is, Chinatown. It is an ironic narrative that comments on ambition, personal desire, and the blind pursuit of betterment of the human race, all causes of political, economic, cultural and historical breakdown in today’s world.

Qiu Zhijie

Qiu Zhijie, Slowly Approaching, 2005

It’s a performance and installation based on the lion dance, a traditional performance based on myths from the Tang Dynasty, which is held on festival days to ward off evil. The artist thinks of the relationship between the elements of “hiding-camouflage”, “play-lion dance”, “performance-Chinatown”, and “display-main exhibition hall” as corresponding to actual problems of ethnic culture. The condition of motion in this work alludes to the “Long March of Chinese culture.” Through his actions, Qiu metaphorically expresses the gap between geopolitics and the migration of cultures as well as the conflicts within the same culture. The performance of the lion dance, carried out in Chinatown and the exhibition hall, is one of the most familiar aspects of Chinese celebrations in China. It will add a festive note to the triennial.

Xu Zhen, 8848, 2005

Xu Zhen’s 8848 is an installation that contains a false documentary video showing the process of carving out the Himalayas as well as fake documents and equipment related to this non-existent project. Xu questions the concept of “the facts”, ironically suggesting that “everything is play-acting,” and the idea of a “universal perception” common to all human beings is false. This also applies to the “facts” that appear in discussions of “transplanted Chinatowns.” Xu’s work explores misreading of Chinese history and their relationship to places of transplanted history, that is, Chinatown. It is an ironic narrative that comments on ambition, personal desire, and the blind pursuit of betterment of the human race, all causes of political, economic, cultural and historical breakdown in today’s world.

Yao Jui-chung

Yao Jui-Chung, The World is For All––China beyond China, 1997

“The World Is For All” is an installation that Yao Jui-Chung has been creating since 1997 featuring images of Chinatowns throughout the world. The artist believes that this phrase, the idealistic slogan of nation-building propounded by Sun Yat-sen, founder of Chinese republic, can be applied to today’s Chinatowns. Chinatowns are special sites, where the historical memories of immigrants are mixed with the cultural characteristics of each location. They are places where people of Chinese origin are at a distance from their native country but also create a boundary bewteen themselves and the place where they live their everyday lives. In this complex social situation, marked by mutual interaction, the inhabitants are engaged in an ambivalent struggle with the problems of their own identity and how to relate to global and local influences.

Chen Xiaoyun

Chen Xiaoyun, Several Moments Extending to a Night, video, 2004

Images here are just some temporary fragments, which are extending to the night or being extended by the night. Turning over the cellar of your memory; climbing up the attic of your unconsciousness; walking into the back garden of your dream; moving over the flagstone of the mouth of your daydream well. Suppose that there are many ways to enter into a night and the entrance to time can be extended by sensation, then time would be just a gift that images contribute to feelings. The scenes in a mass, the obscure tone, the kid show and the mechanical banters, all of them are folded together at the moment when the night is coming. It looks like that there is a horizon waiting for numberless moving scenes.

Zhao Gang

Zhao Gang, The Harlem School of Socialist Realism Study, 2002

The project was initiated by Chinese-American artist Zhao Gang, as a casual discussion around his dinner table in Harlem. Key local African American and Chinese artists and thinkers took part – Satch Hoyt, Franklin Sirmans, Deborah Grant, Lilly Wei, Brett Cook-Dizney and Jeff Sonhouse. They considered the possibility of a New Social Realism, debating the facts and philosophical similarities surrounding the genesis, influences and motivations of revolutionary acts in Chinese and African American society, and the broader global arena.

Anonymous Artist

Anonymous, 21 Go, 2005.

The artist is one who was considered very active in China in the late 1980s but moved to a life in seclusion in a southern Chinese city where they keep a low-key lifestyle and devote themselves to the study of the game of Go.

The game of Go was spread from China to Japan during the Northern and Southern Song period, with the exchange of game tactics and skills between the two countries taking place in the 13th century. The majority of the game’s current players are to be found in Mainland China, Japan, and Taiwan. A number of today’s Go masters are from Taiwan but were taught and/or brought up in Japan; Go is a cultural resource shared by the three regions and is a node of interaction and influence among their histories, cultures, and economies. 21 Go presents a solution of cultural significance to the tensions inherent in the current global geopolitical structure. The creativity of the piece resides in “making another way” (real Go boards are composed of a square grid of 19 lines), and in the utility of the political implications inherent in a “strategy” of “game theory” behaviour. The artist takes a seemingly light-hearted game and uses is to describe the sensitivities and frustrations in the current state of coexistence and contradiction that suffuses Asia’s current political and economic reality, and the potential collusion of interests between the three regions; a “game theory” of an unending break with tradition and conventional awareness.

The execution of this work is formed of two parts: The plan calls for one part (a game or broadcast) in the main exhibition space, the other part (a game or broadcast) will be carried out in Chinatown. Young Go players from Mainland China, Japan and Taiwan will play the game, and the process will be exhibited at the different sites by means of a live video feed.

The artist has decided to hide their name and identity in this work.