Long March – A Walking Visual Display

作品《难民共和国》展在原中华苏维埃中央临时政府前展出-2-400x300.jpg)

Site 1: Ruijin, Jiangxi Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Jun. 28 – Jul. 7, 2002

Site 2: Jinggangshan, Jiangxi Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Jul. 8 – Jul. 12, 2002

Site 3: Daozhong, Guangxi Autonomous Region

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Jul. 13 – Jul. 18, 2002

Site 4: Kunming, Yunnan Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Jul. 21 – Jul.22, Aug. 2 – Aug.5, 2002

Site 5: Lijiang, Yunnan Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Jul. 23 – Jul. 27, 2002

Jul. 31 –Aug.01,2002

Site 6: Lugu Lake, Yunnan/Sichuan Provinces

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Jul. 27 – Jul. 30, 2002

Site 7: On the Train between Kunming and Zunyi

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Aug. 6, 2002

Site 8: Zunyi, Guizhou Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Aug. 7 – Aug. 12, 2002

Site 9: Maotai, Guizhou Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Aug. 13 – Aug. 15, 2002

Site 10: Xichang Long March Satelite Station, Sichuan Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Aug. 16 – Aug. 21

Site 11: Moxi, Sichuan Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Aug. 22 – Aug. 27, 2002

Site 12: From Anshunchang to Luding Bridge

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Aug. 28 – Sep. 1, 2002

Works made along the Long March

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: 2002

Artists: Qu Guangci, Qiu Zhenzhong, Song Dong, Yin Xiuzhen, Wang Bo, Qin Ga, Qiu Zhijie, Ingo Günther, Jiang Jie, Wang Jingsong, Yao Ruizhong, Shao Yinong, Mu Chen, Xiao Lu, Shen Meng, Xiao Xiong, Ding Jie

Site 3: Daozhong, Guangxi Autonomous Region

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Jul. 13 – Jul. 18, 2002

Curatorial Plan: Journey/Pilgrimage/Idol creation – Characters/Historical Fragments/Architectural thresholds

Route: Quanzhou – Longsheng – Sanjiang – Guiyang – Yangshuo

Time: July 13-July 17

July 13-July 14: Quanzhou

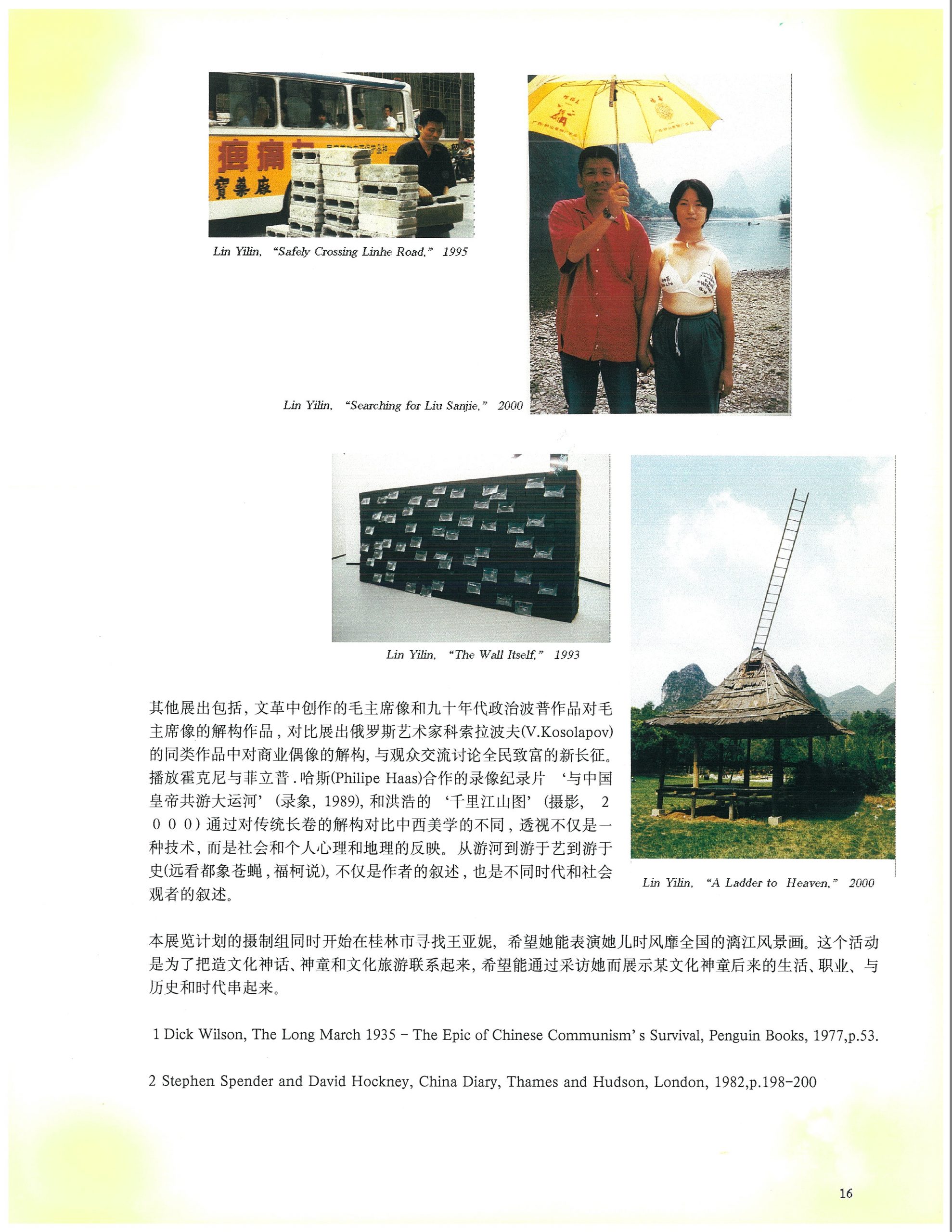

Long March team visited Jiang Jiwei's Stone Carvings at “Marxim Mountain” in Quanzhou

July 15: Longsheng

Set up stalls for art on the road in Guangxi

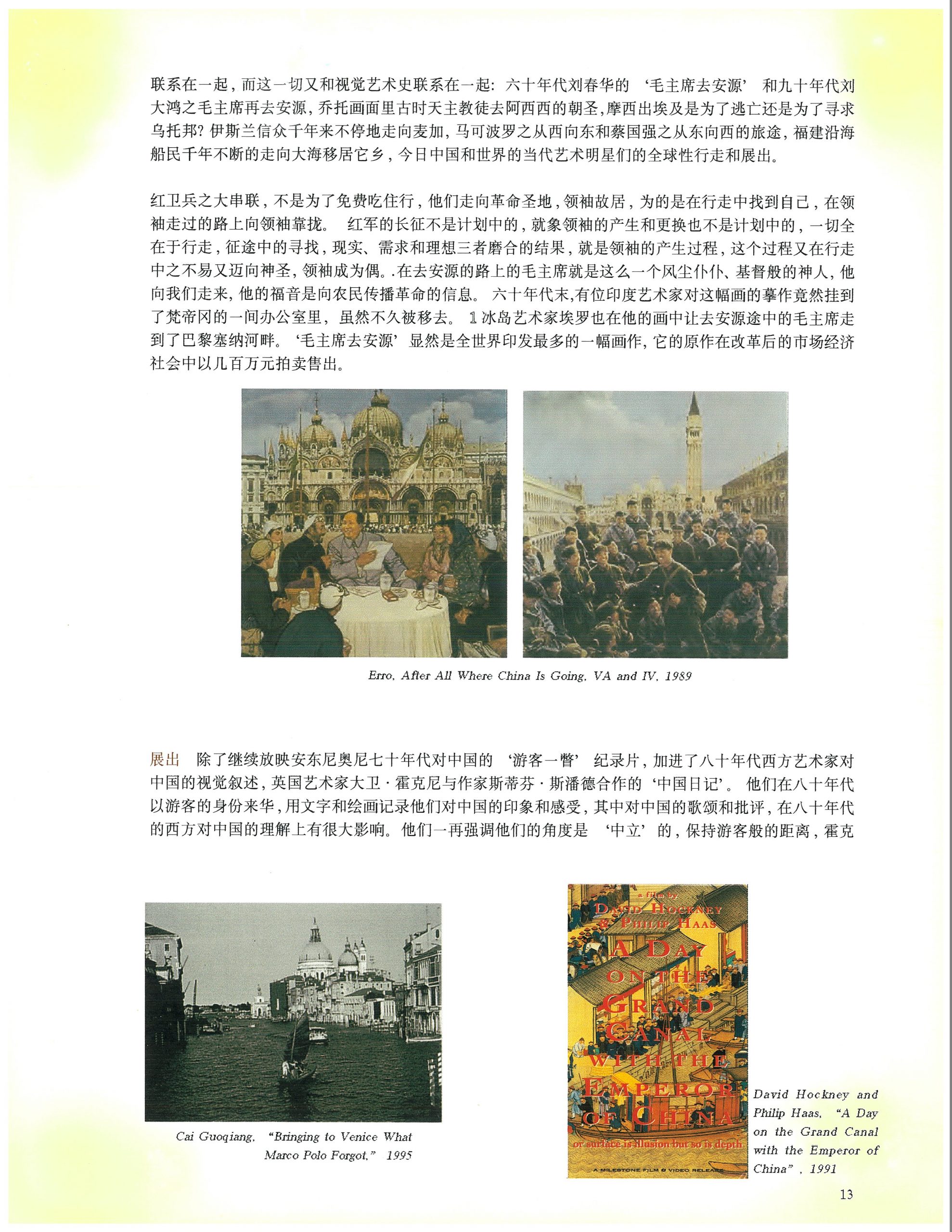

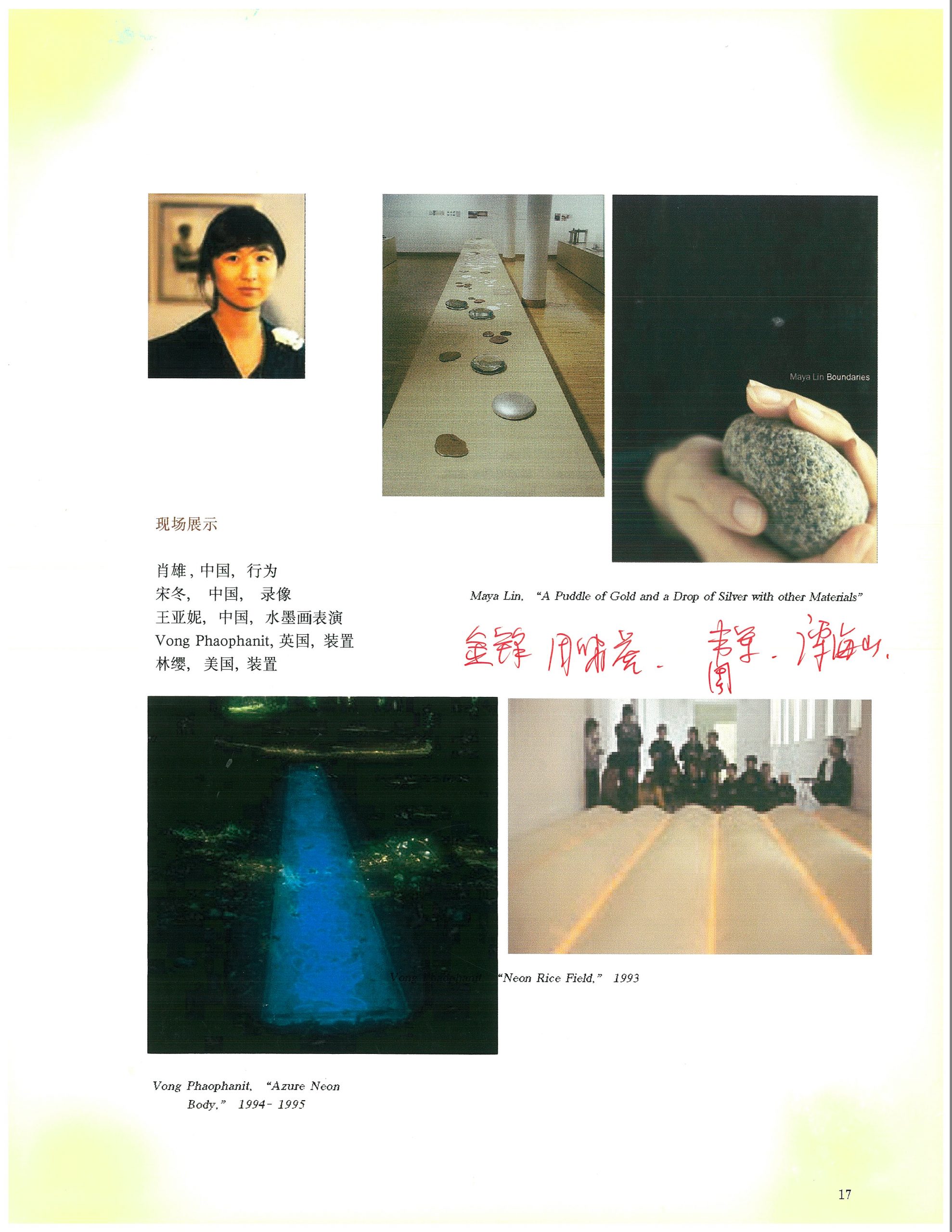

Songdong's work "Shaft-Scenery" exhibited at Red Army Pavilion

July 16: Sanjiang Dong Nationality Autonomous Prefecture

Evening Screening, Dong Village

July 17: Guilin

Screening on the Long-distance Bus to Guilin

Long March Event – Looking for A Xi, Guilin

July 17: Yangshuo

The Long March curatorial crew planned to depart from Jinggangshan at noon on July 12, but found the long-distance bus for Hengyang to be temporarily out of service. Lu Jie and Qiu Zhijie examined a map and reworked their plan of attack. They decided to take a long-distance bus to Zhuzhou instead. The second largest city in Hunan province, Zhuzhou is situated 300 km from Jinggangshan. It is a convenient entry into Guangxi province. Due to a traffic jam caused by rugged road conditions, it was already 9pm when the team arrived in Zhuzhou. Their luggage included works to be exhibited on the road and numbered twenty pieces, large and small. While the crew was unloading luggage, a local pickpocket stole RMB 1300 from Qu Guangci. Thus, the Long March Xiangjiang campaign began with an acute blow.

The curatorial team learned that a bus would depart for Quanzhou that night at 10pm. They promptly hired a Volkswagen Santana and traversed the bustling downtown of Zhuzhou, debarking at the ticket office of the train station. At midnight, the Long Marchers took a moment together to reflect upon the experiences and lessons of their first two weeks on the road. At 5:30 on July 13, the train arrived at the third site of the Long March project, Quanzhou, Guangxi province.

July 13 – July 14

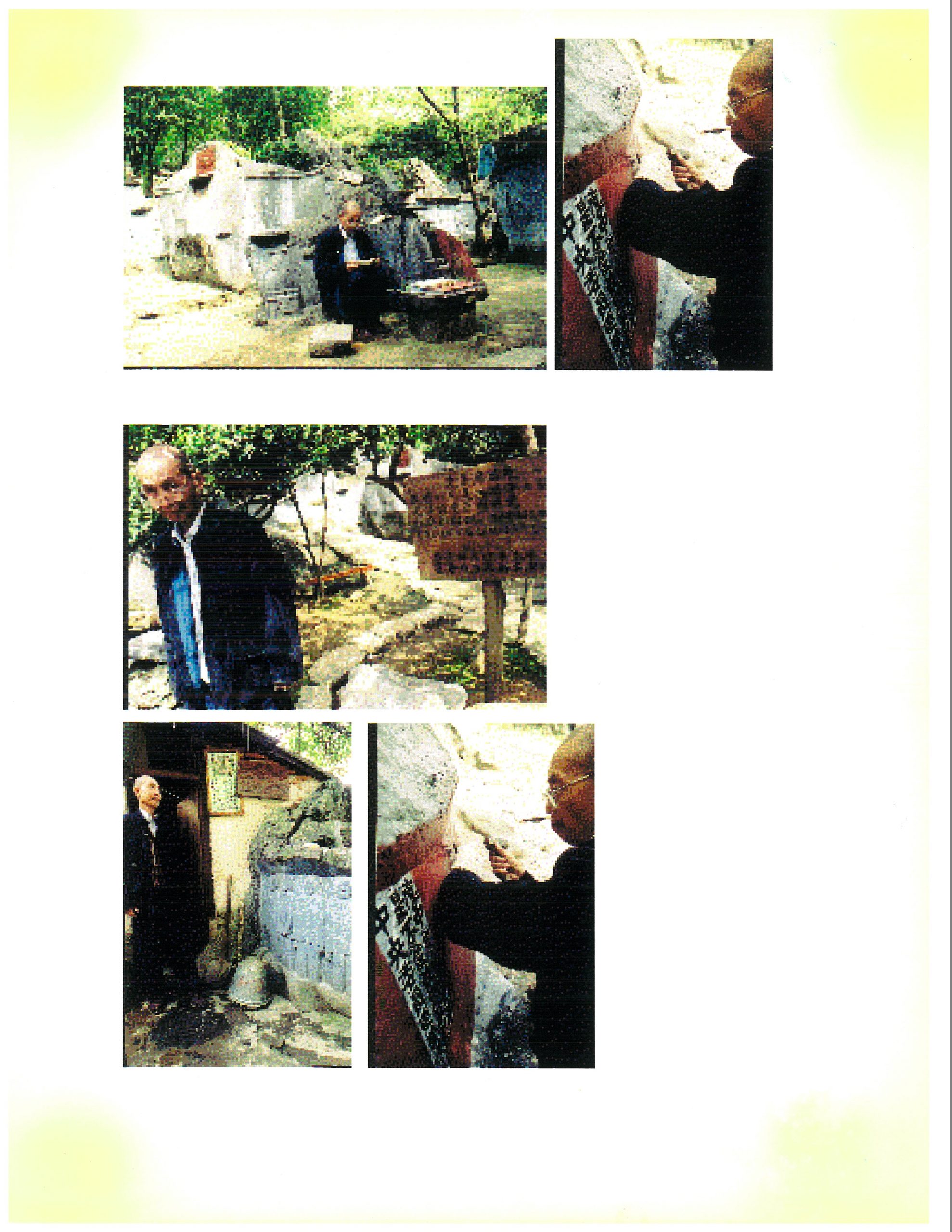

July 13. Quanzhou is situated in northeast Guangxi province. The local dialect sounds quite close to that of Hunan, the neighboring province. The curatorial team’s mission in Quanzhou was to meet a famed old man of wonder. Since the 1970s, this old man has been living among the stone mountains, sculpting bas-reliefs of Mao Zedong and other famous generals and heroes, and engraving quotations from their writings. Because of him, the area has become known as Quotation Mountain.

As they walked around one of the villagers’ houses, a stone forest appeared before them. So vast that it could almost count as a mountain in and of itself, it was filled with bas-reliefs of Lu Xun, Lei Feng, and various other national leaders and generals. Mao Zedong quotations covered the mountaintop. Every character had been carved into the stone with intricate care. The bizarre visual effect created by this sight astonished the curatorial team.

The curators’ first attempt to communicate with Jiang began with writing, which led them to discover some unexpected things. Old Jiang was a local villager. The events he experienced during the Cultural Revolution affected his personality so deeply that he had decided to live far from the rest of the villagers. How and when he took up the sculptor’s knife was not clear, even to Jiang himself. After repeated inquiry by the curatorial team as to what drove him so persistently to make his works, he answered by writing the inescapable slogan “To Serve the People” in big characters.

Looking at the mountain filled with sculptures and engravings, it was hard to imagine that they had been created by an old man without any artistic training. They are simply products of his perseverance and determination. The curatorial team was completely taken aback, and promptly decided to make ink rubbings of his works that can be exhibited and shared with more people on the road. Since Old Jiang’s Quotation Mountain had been under close watch by local officials, making these ink rubbings would require their permission. In order not to miss this opportunity, the curatorial crew decided to part with Old Jiang for now and head back to the city to prepare the materials needed to make ink rubbings.

That night, the Long March film crew also arrived in Quanzhou. They met up with the curatorial crew and discussed the plan.

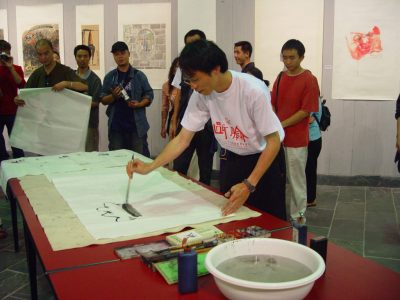

July 14. During the previous day’s visit to Old Jiang, Qiu Zhije busied himself with contacting the village government. Once back on the bus, Qiu Zhijie ripped a piece from his shirt to wrap the rice-paper and ink he had just purchased in town. The village government sent an official named Feng to accompany the Long Marchers. Including the film crew, more than ten people made this second visit to Quotation Mountain.

Qiu Zhijie immediately began to make ink-rubbings. Old Jiang himself was completely shocked at the result, holding the sheet of paper, unable to let go. According to the local official, though many people have visited Quotation Mountain, no one had ever thought of promoting Jiang’s work in such a way. The curatorial team’s undertaking seems to have given much inspiration to the local government. It looks as if ink-rubbing may continue well after the team has departed.

The Long March core crew, wishing not to waste even the night in moving on its next battlefield, wiped away its tears and advanced. The destination: Longsheng County, more than 300 kilometers away. Since the road to Pangsheng is rugged and mountainous, they decided to leave the film crew in Jiantang village to continue shooting Old Jiang. The film crew and the Long March core crew arranged to meet up the following day in the Sanjiang Dong Nationality Autonomous Prefecture.

The Long Marchers, carrying altogether twenty pieces of luggage, split into two cars. The marchers endured nearly seven hours of bumpy roads as the cars navigated the treacherous mountains of northern Guilin. At 11:00 that night, they finally arrived in Longsheng.

In the afternoon, the Long March team met up at the bus station with Feng Qingyu, a female artist from the Yang river area in Guangdong province and her husband. They packed a van full of the Long March’s seven key generals, and set off for the Red Army building in Pingdeng village, some 13 kilometers away. Before departure from the county seat, the team bought a boom box with brightly colored flashing lights, in the style of those carried by fashionable youth during the 1980’s, which would be used for artist Wang Jingsong’s artwork later.

After moving about thirty kilometers, the bus came upon a bustling Dong bazaar. Qiu quickly made a circle of the Dong bazaar stalls, and immediately came upon Lu, who was busy distributing Long March postcardsAs if manna had fallen from above, it became clear that the “streetside market” venue mentioned in the curatorial plan had presented itself within two minutes. The quickly reacting Red Army commanders had made their decision; Qiu quickly chose the perfect stall in which the Long March propaganda team could set up operations. A stall said to sell fake anti-paralysis medications became their sacrificial lamb.

Qiu, unable to refrain from explaining the campaign to the public, set down a strange looking inkbottle. He purchased two sheets of red paper from a neighboring stall and borrowed a brush and some ink, painting Long March – A Walking Visual Display. As the crowd around the stall grew ever larger, commanders Lu and Qiu began to distribute Long March postcards. The Dong villagers were attracted one by one to the stall by these beautiful printed objects, and the postcard bearing a picture of a map became a particularly hot commodity. At the same time, other long marchers displayed original work by Beijing artist Song Dong entitled Changing Directions-Scenery Series. This novel exhibition method attracted serious interest from the villagers, who surrounded Lu Jie and Qiu Zhijie, asking questions about the works they did not understand. They maintained order in the venue on their own, creating an extremely positive atmosphere.

At dusk, after asking several times for directions, the marchers finally arrived at their destination: the Red Army building in the Longping area of Pingdeng village.

At the Red Army building, the marchers used notebook computers to display Ingo Gunther’s “Map” series to the Dong villagers, and to play Lao Jiang’s FLASH animation piece Rock and Roll for the Long March. Of course, the villagers were more interested in the computers and digital cameras the marchers had brought along than in the substance of the broadcasts.

Song Dong’s Changing Directions – Scenery Series was displayed once again. The old people and children sitting in the Red Army building enjoying the cool air became a faithful audience for the exhibition.

The drum tower is often the center of activity in a Dong village, a place where old and young go to meet their peers. The lower floor of the drum tower often covers a main street in the village, turning the building into a resting place along the road, and a site for encountering local personalities. Longping’s two-story drum tower is like this, covering a street. When the Red Army arrived during the historical Long March, the Nationalist generals started a rumor that they were brigands come to rob the villagers with their guns. The Dong villagers fled deep into the mountains. When Mao Zedong and Zhu De quartered in this village, the Nationalists sent special agents to commit arson, and blamed their work on the Red Army. The Red Army struggled and was able to save the drum tower from destruction. This act caused many Dong people to learn of the Red Army, and to support its work. The drum tower was thus named the “Red Army building.”

The Long Marchers moved unceasingly once inside Guangxi province, considering their route, the cultural differences among places on this route, the obstacles they encountered along the way, and their understandings and misunderstandings. When the marchers entered a bazaar or a drum tower together, carrying objects for visual display, they were directly facing the viewers of such a display. They knew they could never prepare sufficiently, but that they must move bravely into each encounter. This was life midway along the Long March.

News arrived that the van had broken down. Finally, the Long Marchers were forced to walk down the mountain road taken by the Red Army all those years ago, experiencing firsthand the hardships and difficulties of marching by night. Qiu used the long-exposure setting on his camera to take a picture of the characters for “Long March,” which he wrote in the air with a flashlight. Even under such extreme conditions, the group was happy.

When the team returned to Pangsheng County, it was already after midnight. In order not to change the plan for the following day’s activities at the fengyu (wind and rain) bridge, at 3:00 that morning, the marchers pitched camp at the Chengyang Qiao Hotel.

Sanjiang Dong Nationality Autonomous Prefecture lies at the border of Hunan, Guangxi, and Guizhou provinces. Dong ethnic customs prevail. In the tiny county seat, one can often see foreign backpackers, come to get a glimpse of the world-famous fengyu bridges, Dong stockaded villages, and drum towers.

Feng Qianyu and her husband had woken up early to prepare for the day’s installation. In town, they bought nearly two hundred meters of metal wire. Using the Internet, they connected with a local travel agency and arranged for a beautiful tour guide, who came to help with the installation.

The fengyu bridge has local characteristics. Like a covered bridge, it is made entirely of wood. Pavilions aligned one after another ensure that the elements do not penetrate the bridge. Chengyang Bridge is famous because it was built without using a single nail. When the crew arrived at Chengyang Bridge, it was already midday. They parked the vans fifty meters away from the bridge. Verifying the suitability of the geographic conditions, Qiu called Feng Qianyu, who had been standing behind him. Throughout the entire assembly process, the group gathered to help Feng complete her work including He Zan, two local workers, Qiu, Long March film crew members, Shen Xiaomin and Old Xu, and others who all stood in the river for an entire afternoon, burning in the sun.

The evening’s screening was very successful. The villagers were moved to laughter by some scenes in the films, which they had never seen before. Aside from the Evans film Wind, Wei Jun’s video work Rules for the Long March, and Yang Fudong’s art films Stealing South and Hey! The Sky is Bright, the movie most adored by the village was without a doubt Lu Ding Ji II. Directed by Wang Jing and starring funnyman Zhou Xingchi, the Hong Kong martial arts film’s screening caused a phenomenon of “a thousand empty rooms” in the tiny village, as everyone came to the square to watch. Villagers said that it had been many years since a movie crew came to screen a film in their village, and that even then they had not shown movies as good as Lu Ding Ji II. Learning from this, Lu temporarily decided that Zhou Xingchi should supplement the artists chosen for the current Long March activities.

Weijun, the Forth Law of the Long March, video, 2002

The Long March activities on the road in Guangxi were well underway. At 11:00, the curatorial crew boarded an air-conditioned coach bound for Guilin from the Sanjiang long-distance bus station. They played the Hong Kong film The Tale of Shushan over the bus’s VCD player. After discussing with the bus driver, the Long March curatorial crew got permission to show Wei Jun’s Rules for the Long March after the first movie ended. Wei Jun’s video work features the artist wearing a Red Army uniform and walking backwards through the streets of Nanning. During post-production, the video was re-recorded in reverse, so it appears that Wei Jun is the only one walking in the right direction, with all other pedestrians walking backwards as if in a comedy.The video lasts around twenty minutes and the choice to view a piece concerning movement as the bus wound its way through mountain roads was no doubt an appropriate one.

Zhou Shaobo, Vietnam, video, 1998

Afterwards, they watched Zhou Shaobo’s documentary film Vietnam. Zhou, a combatant in China’s “war of self-defense” against Vietnam, went again to the country many years later as an ordinary tourist, shooting a documentary from this perspective. The viewers in the car had different reactions to the two works. Some people diligently watched the videos from beginning to end, while others watched only a few minutes and fell asleep, thinking the films were boring. This didn’t matter at all to the creators of the films: after all, the chance to screen works in such a novel venue was a new experience for everyone involved. Just after 15:00, the automobile reached the Guilin long-distance bus station.

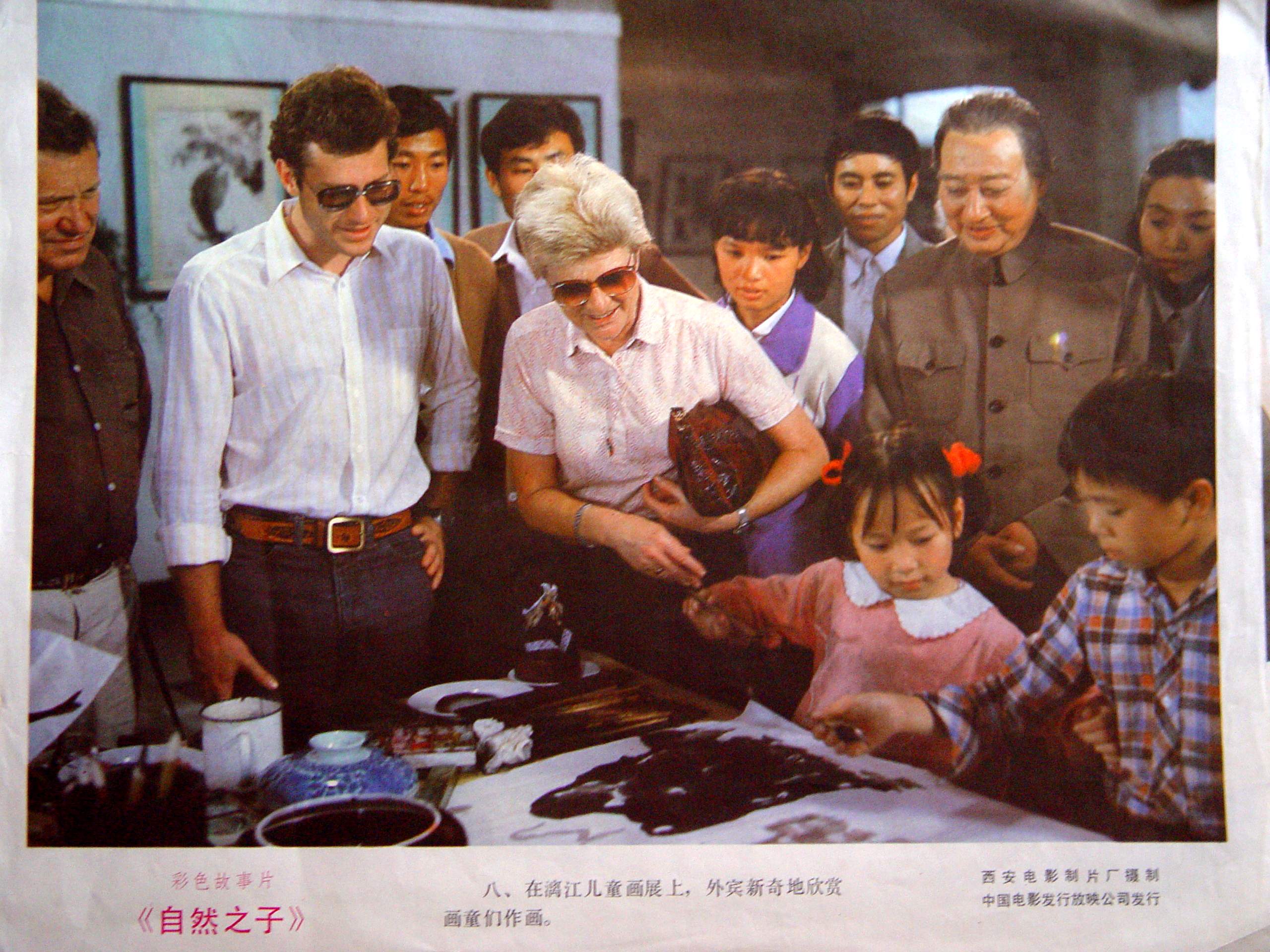

The next activity was to find “whiz kid A Xi,” so named by the Chinese art world of the 1980’s. Wei Jun is the assistant manager of the Guangxi Artists’ Association. Through the association’s connections, he found A Xi’s father. After a few more twists and turns, he found A Xi himself, who now goes by the name of Tan Wenxi. Tan Wenxi warmly received the Long Marchers and film crew, and introduced his present situation to them. The young A Xi’s landscape painting Cat and the Li River won him fame throughout China, and his story was eventually turned into the movie Son of Nature. In this movie, A Xi’s beloved cat is poisoned to death by a child whose paintings are criticized, and A Xi sadly buries the cat. A Xi’s happy image on the cover of People’s Pictorial in 1979 served as an important signal that China’s economy would begin to reform, and that its culture would regain importance. As a teenager, A Xi changed the focus of his studies to Western-style charcoal drawing, and changed his name to Tan Wenxi. He began his studies at the Central Academy of Art and Design, but was forced to stop after an automobile accident. Now, the handicapped Tan Wenxi remains in his home, where he teaches a preparatory course for students looking to test into art school. He also continues to paint in oil. In talking about his earlier experience of being made into a star as a child prodigy, he noted that it not only brought him no perks as a student, but also created a great deal of pressure. He hopes there will not be another “whiz kid” in the future. He says that for a long time he thought his childhood paintings were silly, and that only in recent years has he begun once again to like these works.

Leaving A Xi’s home, there was no time to think. The group threw together a quick meal and boarded the bus for Yangshuo, arriving as the sky was getting dark. Yangshuo is a classic tourist town, its “Westerners’ Street” a simultaneous incarnation of Beijing’s Sanlitun bar street and Panjiayuan antique market. Full of blonde-haired, blue-eyed foreigners indulging in worldly pleasures, this unique environment brought to the foreground the series of questions the Long March’s Guangxi activities had raised about movement, memory, encounter, misunderstanding, transmission, and remains.

That night, the marchers hung a screen in the middle of Yangshuo’s bar street, and played a series of video works for the Chinese and foreign tourists passing by. These included Wind, Yang Fudong’s work Stealing South, and Zhou Xiaohu’s works Nursery Rhymes and Journey of Desire among others. Meanwhile, “Qu Guangci” made a flamboyant entry, playing the role of a very strange interloper among the crowd.

The screening lasted past midnight, and a seemingly endless series of activities in Guangxi province came to a happy end. The next day, the Long Marchers returned to Guilin to rest and reorganize, preparing to depart on July 19 for their next stop: Kunming.

Curatorial Plan: Journey/Pilgrimage/Idol creation – Characters/Historical Fragments/Architectural thresholds

Route: Quanzhou – Longsheng – Sanjiang – Guiyang – Yangshuo

Time: July 13-July 17

July 13-July 14: Quanzhou

Long March team visited Jiang Jiwei's Stone Carvings at “Marxim Mountain” in Quanzhou

July 15: Longsheng

Set up stalls for art on the road in Guangxi

Songdong's work "Shaft-Scenery" exhibited at Red Army Pavilion

July 16: Sanjiang Dong Nationality Autonomous Prefecture

Evening Screening, Dong Village

July 17: Guilin

Screening on the Long-distance Bus to Guilin

Long March Event – Looking for A Xi, Guilin

July 17: Yangshuo

July 13. Quanzhou is situated in northeast Guangxi province. The local dialect sounds quite close to that of Hunan, the neighboring province. The curatorial team’s mission in Quanzhou was to meet a famed old man of wonder. Since the 1970s, this old man has been living among the stone mountains, sculpting bas-reliefs of Mao Zedong and other famous generals and heroes, and engraving quotations from their writings. Because of him, the area has become known as Quotation Mountain.

As they walked around one of the villagers’ houses, a stone forest appeared before them. So vast that it could almost count as a mountain in and of itself, it was filled with bas-reliefs of Lu Xun, Lei Feng, and various other national leaders and generals. Mao Zedong quotations covered the mountaintop. Every character had been carved into the stone with intricate care. The bizarre visual effect created by this sight astonished the curatorial team.

The curators’ first attempt to communicate with Jiang began with writing, which led them to discover some unexpected things. Old Jiang was a local villager. The events he experienced during the Cultural Revolution affected his personality so deeply that he had decided to live far from the rest of the villagers. How and when he took up the sculptor’s knife was not clear, even to Jiang himself. After repeated inquiry by the curatorial team as to what drove him so persistently to make his works, he answered by writing the inescapable slogan “To Serve the People” in big characters.

Looking at the mountain filled with sculptures and engravings, it was hard to imagine that they had been created by an old man without any artistic training. They are simply products of his perseverance and determination. The curatorial team was completely taken aback, and promptly decided to make ink rubbings of his works that can be exhibited and shared with more people on the road. Since Old Jiang’s Quotation Mountain had been under close watch by local officials, making these ink rubbings would require their permission. In order not to miss this opportunity, the curatorial crew decided to part with Old Jiang for now and head back to the city to prepare the materials needed to make ink rubbings.

That night, the Long March film crew also arrived in Quanzhou. They met up with the curatorial crew and discussed the plan.

July 14. During the previous day’s visit to Old Jiang, Qiu Zhije busied himself with contacting the village government. Once back on the bus, Qiu Zhijie ripped a piece from his shirt to wrap the rice-paper and ink he had just purchased in town. The village government sent an official named Feng to accompany the Long Marchers. Including the film crew, more than ten people made this second visit to Quotation Mountain.

Qiu Zhijie immediately began to make ink-rubbings. Old Jiang himself was completely shocked at the result, holding the sheet of paper, unable to let go. According to the local official, though many people have visited Quotation Mountain, no one had ever thought of promoting Jiang’s work in such a way. The curatorial team’s undertaking seems to have given much inspiration to the local government. It looks as if ink-rubbing may continue well after the team has departed.

The Long March core crew, wishing not to waste even the night in moving on its next battlefield, wiped away its tears and advanced. The destination: Longsheng County, more than 300 kilometers away. Since the road to Pangsheng is rugged and mountainous, they decided to leave the film crew in Jiantang village to continue shooting Old Jiang. The film crew and the Long March core crew arranged to meet up the following day in the Sanjiang Dong Nationality Autonomous Prefecture.

The Long Marchers, carrying altogether twenty pieces of luggage, split into two cars. The marchers endured nearly seven hours of bumpy roads as the cars navigated the treacherous mountains of northern Guilin. At 11:00 that night, they finally arrived in Longsheng.

In the afternoon, the Long March team met up at the bus station with Feng Qingyu, a female artist from the Yang river area in Guangdong province and her husband. They packed a van full of the Long March’s seven key generals, and set off for the Red Army building in Pingdeng village, some 13 kilometers away. Before departure from the county seat, the team bought a boom box with brightly colored flashing lights, in the style of those carried by fashionable youth during the 1980’s, which would be used for artist Wang Jingsong’s artwork later.

After moving about thirty kilometers, the bus came upon a bustling Dong bazaar. Qiu quickly made a circle of the Dong bazaar stalls, and immediately came upon Lu, who was busy distributing Long March postcardsAs if manna had fallen from above, it became clear that the “streetside market” venue mentioned in the curatorial plan had presented itself within two minutes. The quickly reacting Red Army commanders had made their decision; Qiu quickly chose the perfect stall in which the Long March propaganda team could set up operations. A stall said to sell fake anti-paralysis medications became their sacrificial lamb.

Qiu, unable to refrain from explaining the campaign to the public, set down a strange looking inkbottle. He purchased two sheets of red paper from a neighboring stall and borrowed a brush and some ink, painting Long March – A Walking Visual Display. As the crowd around the stall grew ever larger, commanders Lu and Qiu began to distribute Long March postcards. The Dong villagers were attracted one by one to the stall by these beautiful printed objects, and the postcard bearing a picture of a map became a particularly hot commodity. At the same time, other long marchers displayed original work by Beijing artist Song Dong entitled Changing Directions-Scenery Series. This novel exhibition method attracted serious interest from the villagers, who surrounded Lu Jie and Qiu Zhijie, asking questions about the works they did not understand. They maintained order in the venue on their own, creating an extremely positive atmosphere.

At dusk, after asking several times for directions, the marchers finally arrived at their destination: the Red Army building in the Longping area of Pingdeng village.

At the Red Army building, the marchers used notebook computers to display Ingo Gunther’s “Map” series to the Dong villagers, and to play Lao Jiang’s FLASH animation piece Rock and Roll for the Long March. Of course, the villagers were more interested in the computers and digital cameras the marchers had brought along than in the substance of the broadcasts.

Song Dong’s Changing Directions – Scenery Series was displayed once again. The old people and children sitting in the Red Army building enjoying the cool air became a faithful audience for the exhibition.

The drum tower is often the center of activity in a Dong village, a place where old and young go to meet their peers. The lower floor of the drum tower often covers a main street in the village, turning the building into a resting place along the road, and a site for encountering local personalities. Longping’s two-story drum tower is like this, covering a street. When the Red Army arrived during the historical Long March, the Nationalist generals started a rumor that they were brigands come to rob the villagers with their guns. The Dong villagers fled deep into the mountains. When Mao Zedong and Zhu De quartered in this village, the Nationalists sent special agents to commit arson, and blamed their work on the Red Army. The Red Army struggled and was able to save the drum tower from destruction. This act caused many Dong people to learn of the Red Army, and to support its work. The drum tower was thus named the “Red Army building.”

The Long Marchers moved unceasingly once inside Guangxi province, considering their route, the cultural differences among places on this route, the obstacles they encountered along the way, and their understandings and misunderstandings. When the marchers entered a bazaar or a drum tower together, carrying objects for visual display, they were directly facing the viewers of such a display. They knew they could never prepare sufficiently, but that they must move bravely into each encounter. This was life midway along the Long March.

News arrived that the van had broken down. Finally, the Long Marchers were forced to walk down the mountain road taken by the Red Army all those years ago, experiencing firsthand the hardships and difficulties of marching by night. Qiu used the long-exposure setting on his camera to take a picture of the characters for “Long March,” which he wrote in the air with a flashlight. Even under such extreme conditions, the group was happy.

When the team returned to Pangsheng County, it was already after midnight. In order not to change the plan for the following day’s activities at the fengyu (wind and rain) bridge, at 3:00 that morning, the marchers pitched camp at the Chengyang Qiao Hotel.

Sanjiang Dong Nationality Autonomous Prefecture lies at the border of Hunan, Guangxi, and Guizhou provinces. Dong ethnic customs prevail. In the tiny county seat, one can often see foreign backpackers, come to get a glimpse of the world-famous fengyu bridges, Dong stockaded villages, and drum towers.

Feng Qianyu and her husband had woken up early to prepare for the day’s installation. In town, they bought nearly two hundred meters of metal wire. Using the Internet, they connected with a local travel agency and arranged for a beautiful tour guide, who came to help with the installation.

The fengyu bridge has local characteristics. Like a covered bridge, it is made entirely of wood. Pavilions aligned one after another ensure that the elements do not penetrate the bridge. Chengyang Bridge is famous because it was built without using a single nail. When the crew arrived at Chengyang Bridge, it was already midday. They parked the vans fifty meters away from the bridge. Verifying the suitability of the geographic conditions, Qiu called Feng Qianyu, who had been standing behind him. Throughout the entire assembly process, the group gathered to help Feng complete her work including He Zan, two local workers, Qiu, Long March film crew members, Shen Xiaomin and Old Xu, and others who all stood in the river for an entire afternoon, burning in the sun.

The evening’s screening was very successful. The villagers were moved to laughter by some scenes in the films, which they had never seen before. Aside from the Evans film Wind, Wei Jun’s video work Rules for the Long March, and Yang Fudong’s art films Stealing South and Hey! The Sky is Bright, the movie most adored by the village was without a doubt Lu Ding Ji II. Directed by Wang Jing and starring funnyman Zhou Xingchi, the Hong Kong martial arts film’s screening caused a phenomenon of “a thousand empty rooms” in the tiny village, as everyone came to the square to watch. Villagers said that it had been many years since a movie crew came to screen a film in their village, and that even then they had not shown movies as good as Lu Ding Ji II. Learning from this, Lu temporarily decided that Zhou Xingchi should supplement the artists chosen for the current Long March activities.

Weijun, the Forth Law of the Long March, video, 2002

The Long March activities on the road in Guangxi were well underway. At 11:00, the curatorial crew boarded an air-conditioned coach bound for Guilin from the Sanjiang long-distance bus station. They played the Hong Kong film The Tale of Shushan over the bus’s VCD player. After discussing with the bus driver, the Long March curatorial crew got permission to show Wei Jun’s Rules for the Long March after the first movie ended. Wei Jun’s video work features the artist wearing a Red Army uniform and walking backwards through the streets of Nanning. During post-production, the video was re-recorded in reverse, so it appears that Wei Jun is the only one walking in the right direction, with all other pedestrians walking backwards as if in a comedy.The video lasts around twenty minutes and the choice to view a piece concerning movement as the bus wound its way through mountain roads was no doubt an appropriate one.

Zhou Shaobo, Vietnam, video, 1998

Afterwards, they watched Zhou Shaobo’s documentary film Vietnam. Zhou, a combatant in China’s “war of self-defense” against Vietnam, went again to the country many years later as an ordinary tourist, shooting a documentary from this perspective. The viewers in the car had different reactions to the two works. Some people diligently watched the videos from beginning to end, while others watched only a few minutes and fell asleep, thinking the films were boring. This didn’t matter at all to the creators of the films: after all, the chance to screen works in such a novel venue was a new experience for everyone involved. Just after 15:00, the automobile reached the Guilin long-distance bus station.

The next activity was to find “whiz kid A Xi,” so named by the Chinese art world of the 1980’s. Wei Jun is the assistant manager of the Guangxi Artists’ Association. Through the association’s connections, he found A Xi’s father. After a few more twists and turns, he found A Xi himself, who now goes by the name of Tan Wenxi. Tan Wenxi warmly received the Long Marchers and film crew, and introduced his present situation to them. The young A Xi’s landscape painting Cat and the Li River won him fame throughout China, and his story was eventually turned into the movie Son of Nature. In this movie, A Xi’s beloved cat is poisoned to death by a child whose paintings are criticized, and A Xi sadly buries the cat. A Xi’s happy image on the cover of People’s Pictorial in 1979 served as an important signal that China’s economy would begin to reform, and that its culture would regain importance. As a teenager, A Xi changed the focus of his studies to Western-style charcoal drawing, and changed his name to Tan Wenxi. He began his studies at the Central Academy of Art and Design, but was forced to stop after an automobile accident. Now, the handicapped Tan Wenxi remains in his home, where he teaches a preparatory course for students looking to test into art school. He also continues to paint in oil. In talking about his earlier experience of being made into a star as a child prodigy, he noted that it not only brought him no perks as a student, but also created a great deal of pressure. He hopes there will not be another “whiz kid” in the future. He says that for a long time he thought his childhood paintings were silly, and that only in recent years has he begun once again to like these works.

Leaving A Xi’s home, there was no time to think. The group threw together a quick meal and boarded the bus for Yangshuo, arriving as the sky was getting dark. Yangshuo is a classic tourist town, its “Westerners’ Street” a simultaneous incarnation of Beijing’s Sanlitun bar street and Panjiayuan antique market. Full of blonde-haired, blue-eyed foreigners indulging in worldly pleasures, this unique environment brought to the foreground the series of questions the Long March’s Guangxi activities had raised about movement, memory, encounter, misunderstanding, transmission, and remains.

That night, the marchers hung a screen in the middle of Yangshuo’s bar street, and played a series of video works for the Chinese and foreign tourists passing by. These included Wind, Yang Fudong’s work Stealing South, and Zhou Xiaohu’s works Nursery Rhymes and Journey of Desire among others. Meanwhile, “Qu Guangci” made a flamboyant entry, playing the role of a very strange interloper among the crowd.

The screening lasted past midnight, and a seemingly endless series of activities in Guangxi province came to a happy end. The next day, the Long Marchers returned to Guilin to rest and reorganize, preparing to depart on July 19 for their next stop: Kunming.