Long March – A Walking Visual Display

作品《难民共和国》展在原中华苏维埃中央临时政府前展出-2-400x300.jpg)

Site 1: Ruijin, Jiangxi Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Jun. 28 – Jul. 7, 2002

Site 2: Jinggangshan, Jiangxi Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Jul. 8 – Jul. 12, 2002

Site 3: Daozhong, Guangxi Autonomous Region

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Jul. 13 – Jul. 18, 2002

Site 4: Kunming, Yunnan Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Jul. 21 – Jul.22, Aug. 2 – Aug.5, 2002

Site 5: Lijiang, Yunnan Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Jul. 23 – Jul. 27, 2002

Jul. 31 –Aug.01,2002

Site 6: Lugu Lake, Yunnan/Sichuan Provinces

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Jul. 27 – Jul. 30, 2002

Site 7: On the Train between Kunming and Zunyi

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Aug. 6, 2002

Site 8: Zunyi, Guizhou Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Aug. 7 – Aug. 12, 2002

Site 9: Maotai, Guizhou Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Aug. 13 – Aug. 15, 2002

Site 10: Xichang Long March Satelite Station, Sichuan Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Aug. 16 – Aug. 21

Site 11: Moxi, Sichuan Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Aug. 22 – Aug. 27, 2002

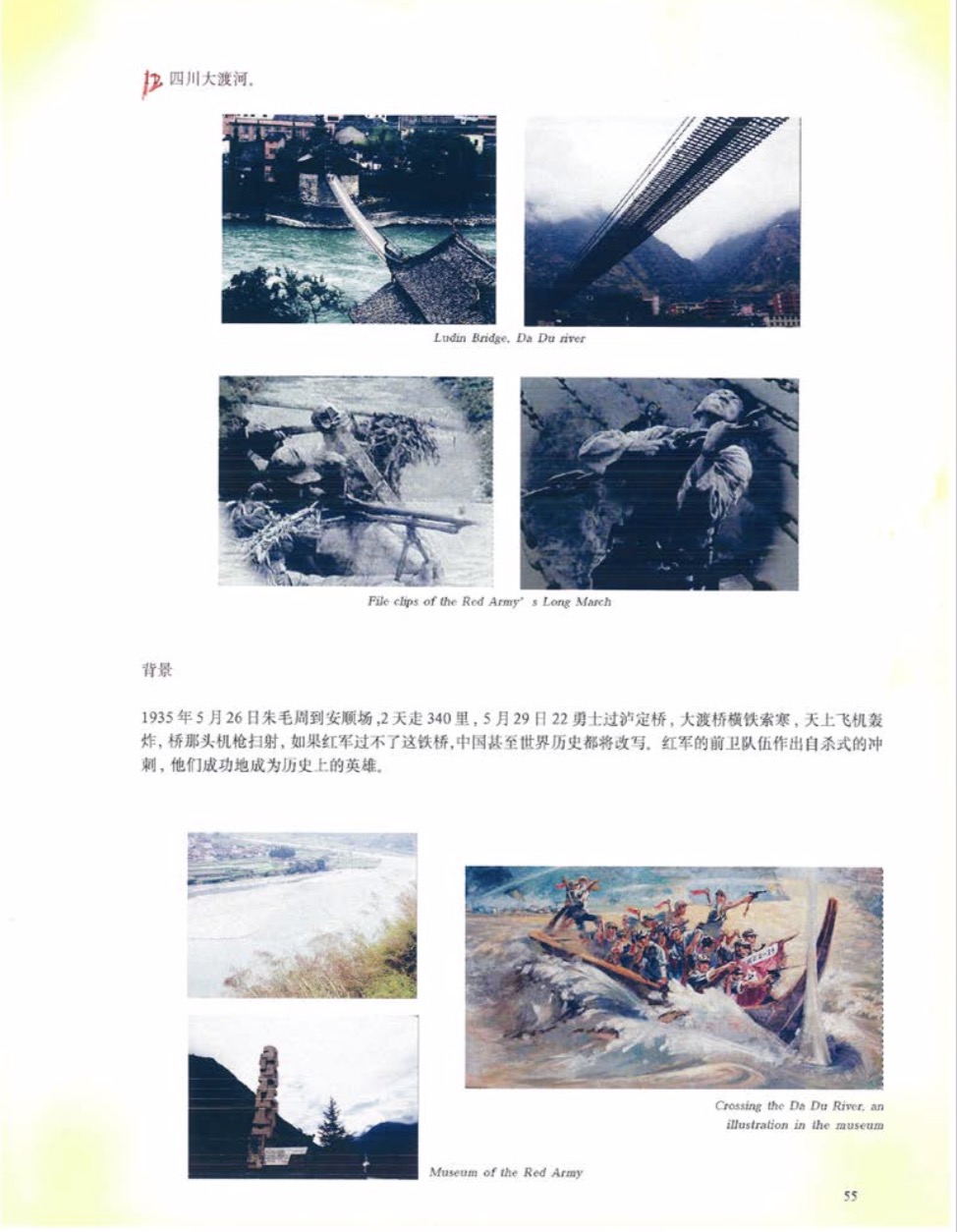

Site 12: From Anshunchang to Luding Bridge

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Aug. 28 – Sep. 1, 2002

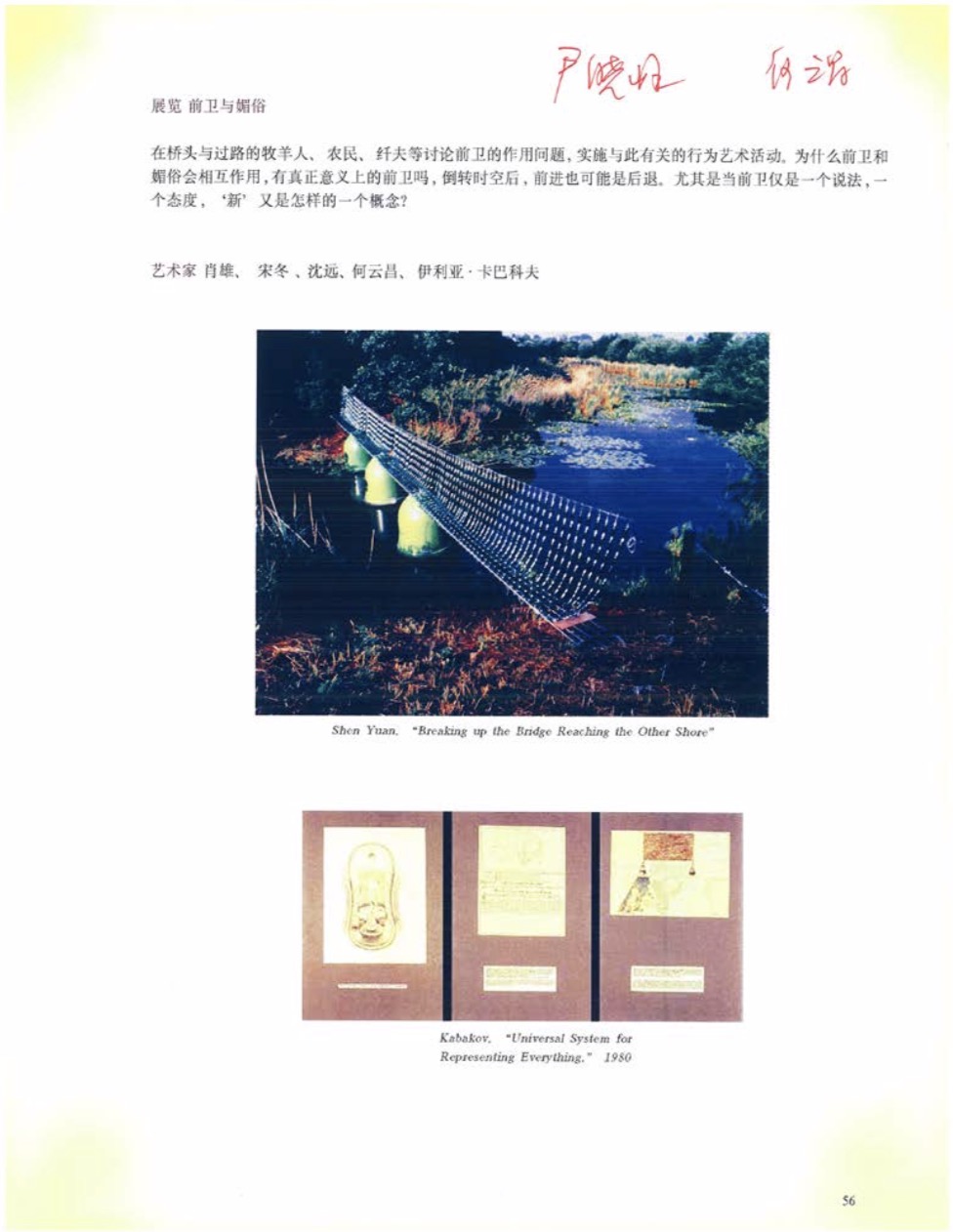

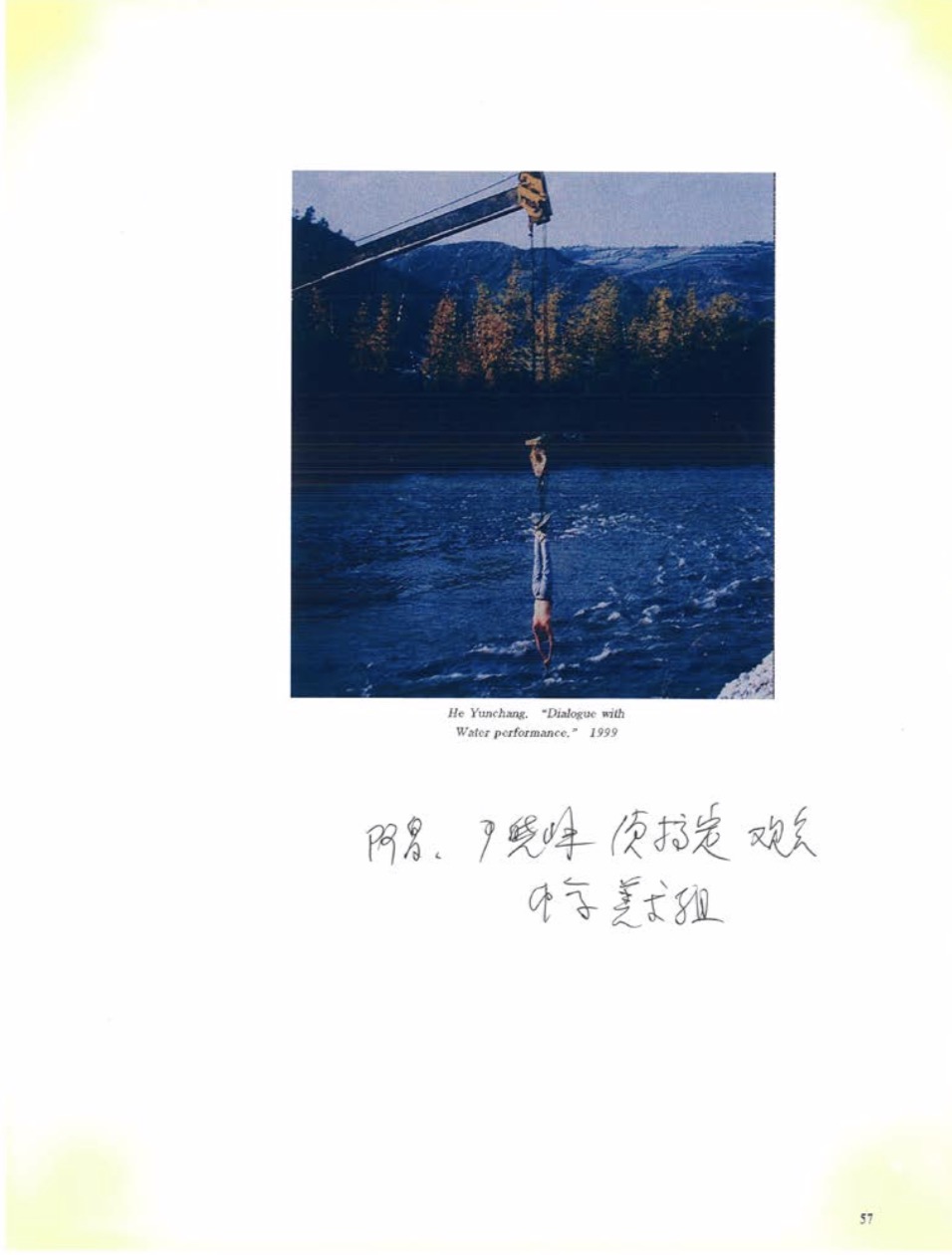

Works made along the Long March

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: 2002

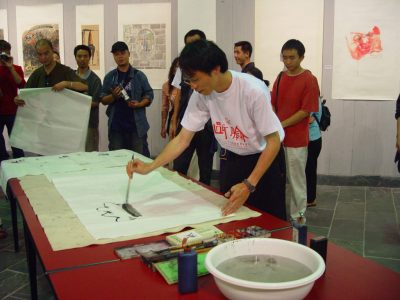

Artists: Qu Guangci, Qiu Zhenzhong, Song Dong, Yin Xiuzhen, Wang Bo, Qin Ga, Qiu Zhijie, Ingo Günther, Jiang Jie, Wang Jingsong, Yao Ruizhong, Shao Yinong, Mu Chen, Xiao Lu, Shen Meng, Xiao Xiong, Ding Jie

Site 12: From Anshunchang to Luding Bridge

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Aug. 28 – Sep. 1, 2002

Curatorial Plan: The vanguard unit of the Red Army made history and saved the army from annihilation, or did history create the legend of the vanguard unit – the historical context of historical events and the related narrative and interpretations

Route: from Anshunchang to Luding Bridge

Time: 2002.8.28-9.1

August 29-September 1:Luding Bridge

Long March Event – “Blind Man Crossing a Bridge”

Qiu Zhijie’s Left /Right and Discussion on

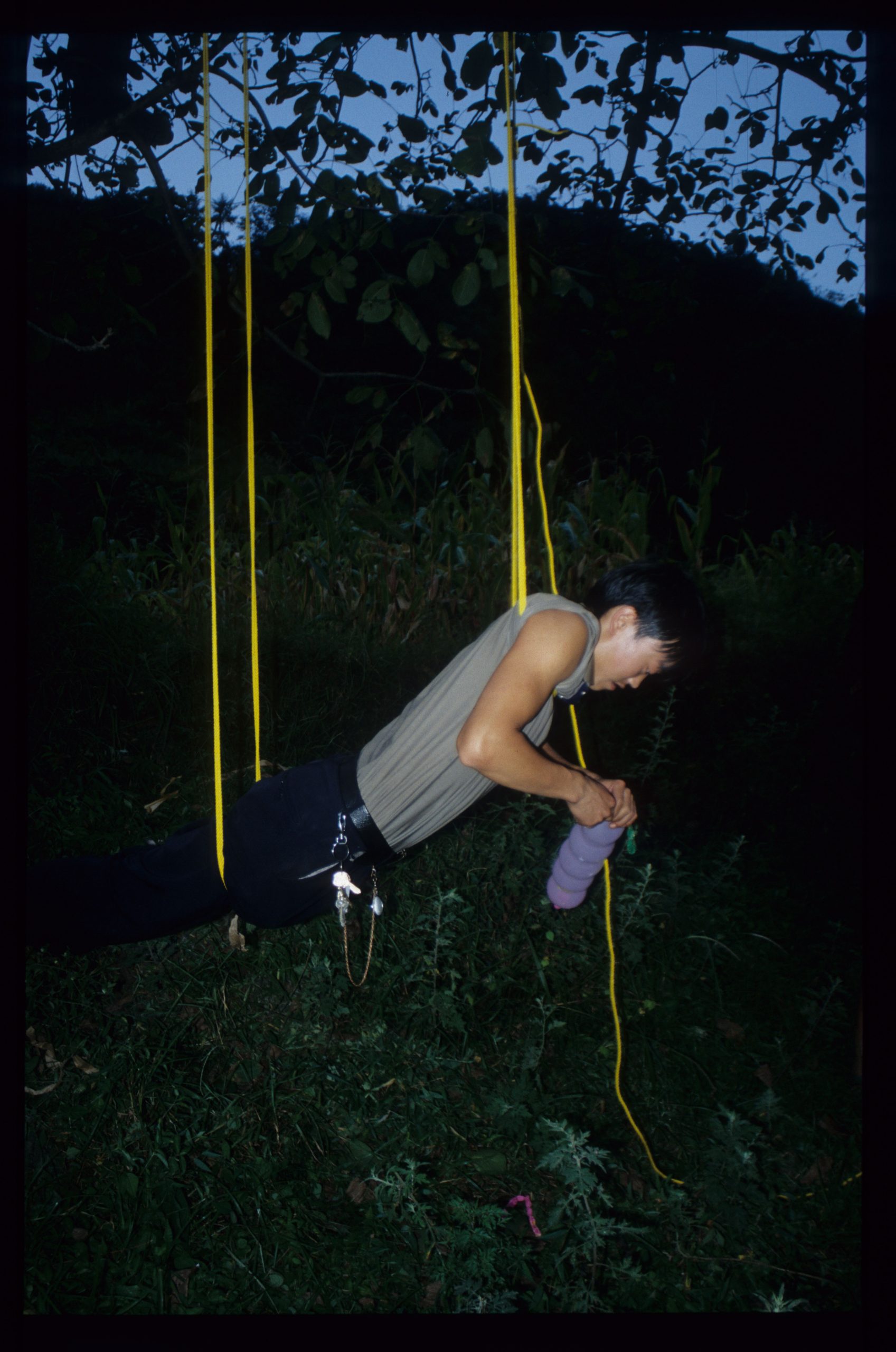

Qu Guangci, Model Sodier of the New Long March, performance

Homage to Performance Art (Ten Farewells to Avant-garde), performance, and Wang Jianwei, Interspace, performance/video

August 29

The meaning of the Long March Event “Blind Man Crossing a Bridge” was in its connection to a personal experience that unfolded at a rather large distance from the historical narrative, and in discussing these topics from this perspective. A blind man cannot see the countless propaganda paintings and sculptures of the “flying battle at Luding Bridge,” nor can he view the countless reconstitutions of these events on film and television. His connection with Luding Bridge is more fundamental, more visceral. He crosses the bridge holding onto the iron chains, his ears filled with the rushing sounds of the Dadu River. His connection with the historical narrative of this place is remote, and his blindness exposes a reality: our historical consciousness, like his perceptive ability, is built on a certain degree of illusion, and the role of visual culture in developing that consciousness and guiding that discourse is not insignificant. The relationship between personal experience and historical consciousness is at least food for thought. How, then, does the blind man see the avant-garde?

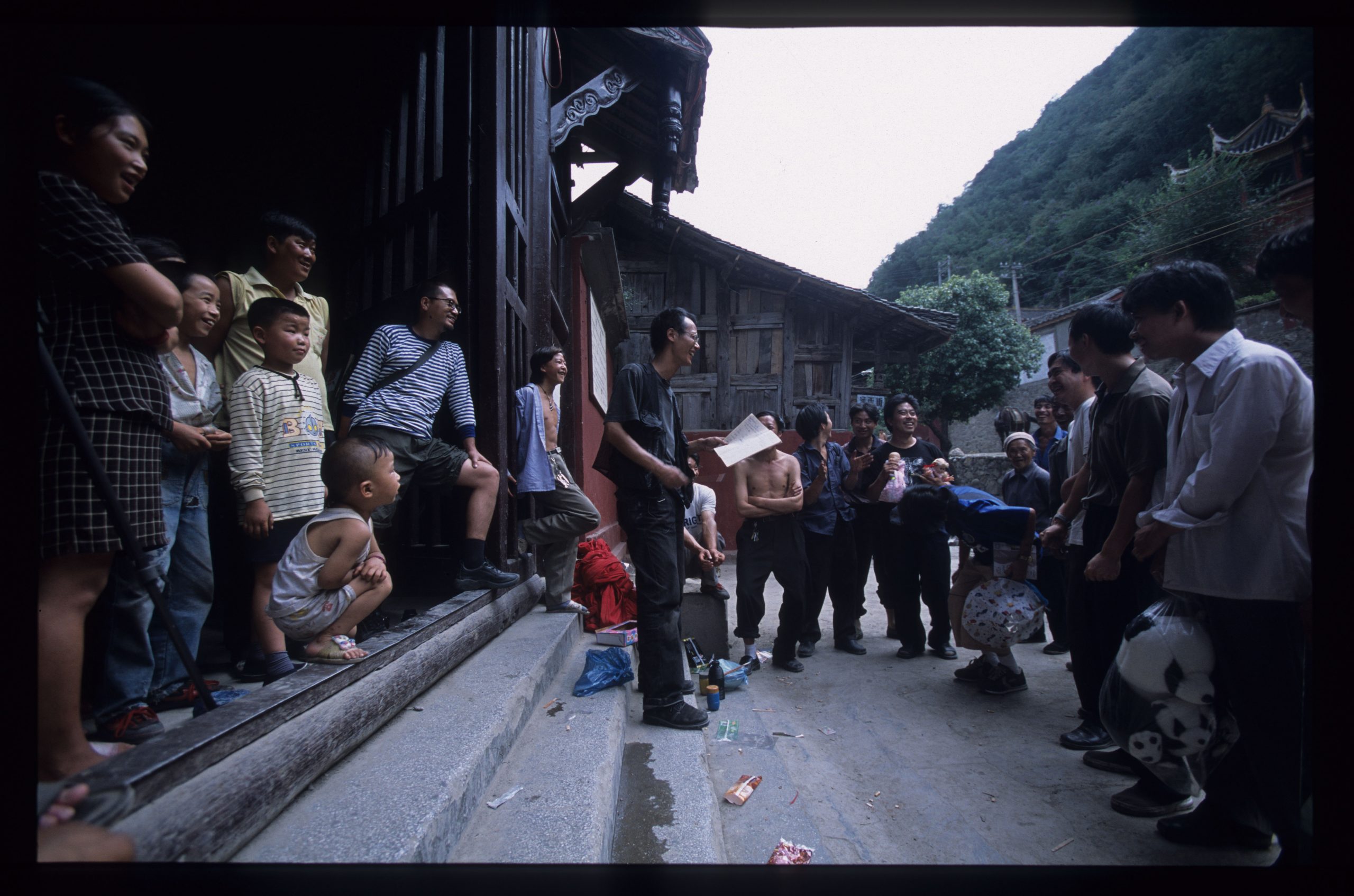

At 9:30, Lu Jie and company set out from Moxi for Luding, greeted as soon as they stepped off the bus by Qiu Zhijie and Blind Masseur Deng who had been waiting for hours. They immediately crossed Luding Bridge, walking and talking simultaneously.

Blind Masseur Deng had a very definite response to the avant-garde: if twenty-two soldiers had not crossed Luding Bridge, he thought, the overall direction of the Chinese revolution would not have changed, but it would have been influenced greatly. The place of the avant-garde is to speed up the development of history: this was Deng’s theory.

After talking with him, at 10:30 and again at 16:30, Qiu Zhijie donned a blindfold and walked across Luding Bridge, realizing his work Left Right. The difference between everyday behavior and theatricality, between artwork and non-artwork, the vagueness of the border between intention and non-intention made this work become randomly apparent and invisible, appearing and disappearing with no regularity. His walking became a dialectic of forgetting and remembering: walking is inherently continuous, only consciousness is fragmented. Today, amidst the theatricality of Luding Bridge, Qiu Zhijie decided to leave some intentional traces.

He placed segments of wet cloth at five intervals across the bridge, and covered his eyes with a black blindfold. He walked wobblingly across the bridge from the west to the east tower, leaving clear footprints in water on the wooden planks.

The danger of walking Luding Bridge turned this work into a commentary on the fate of the avant-garde. As an artist and at the same time a curator of the Long March, every step Qiu took in thought was as adventurous as a physical step across the bridge, and as the work suggested, involved a constant negotiation between left and right. Every step involved a clear choice between left and right, radical and conservative, right and wrong. If judgments were so clear, was there any need for a Long March?

That evening, Lu Jie and Qiu Zhijie talked late into the night, figuring out how to continue with the Long March plan. They had the progress they had already made clearly in mind. They were completely confident in their ability to finish the Long March on schedule, as twelve of the twenty sites had already been completed. They had some regrets, but more important, they had grown accustomed to life on the road. What were the possibilities of the Long March? A larger kind of doubt filled their minds.

They knew clearly, this sort of doubt would lead to a certain kind of action, and this action might set off a chain reaction. They were between a rock and a hard place, and the work Left Right seemed to have taken on a fateful role. But the Long March could not become a matter of fate.

They called in Lisa, Shen Xiaomin, Jeff, and Yang Jie to participate in the debate. Shi Qing, as an artist on the site, also took part.

Democracy had not confused everyone, and by 4:30 on the morning of the 30th, a bold new idea had taken shape.

August 30

At midday, on the west side of Luding Bridge, next to a marker commemorating the Kangxi emperor, the Marchers undertook the second monthly vote count for Qu Guangci’s work Model Soldier of the New Long March. As always, this procedure was led by “Qu Guangci,” with Lu Jie calling out the ballots and Qiu Zhijie recording them. In the end, a tanned, thin Qiu Zhijie was chosen as the second “Model Soldier of the New Long March.”

After the ballots had been counted, the camera crew interviewed “Qu Guangci.”

“Qu Guangci” bashfully said, “I had a dream, I dreamed that my daughter grew up and became an artist.”

That night, Beijing artist Wang Jianwei reached Luding, uncontrollably excited.

By night, Luding Bridge already had the subtle cold of early autumn. Lu Jie and Qiu Zhijie brought up the things they had been considering to Wang Jianwei. They recalled how eleven months earlier, the three of them had been sitting in the garden behind Lu Jie’s house in New Jersey, eating crabs and drinking, similarly talking about the Long March.

Wang Jianwei said in a flash, “Contemporary art requires us to keep ourselves confused; laying things out too clearly is dangerous.”

The three didn’t speak, rubbing their hands along the mottled chains of the bridge, listening to the river roar beneath their feet. Wang Jianwei at that moment pointed out that the historical Long March was divided into two segments. With Luding Bridge as the dividing line, the first half involved the Red Army’s struggle against the Nationalist Army, while in the second half they had shed the pursuing army, and were concerned only with carving the right path for themselves. As Deng Xiaoping said, here they were “going with the road.” Unexpectedly this conversation became prophetic, and Wang Jianwei’s work titled Middle Segment became this Long March’s first punctuation mark.

At the dinner table, everyone eagerly praised the ten brave souls who put on the evening’s performances. A phone call came from Chengdu, where artists Yu Ji and Dai Guangyu were waiting for orders, and from Beijing where Sun Yuan and Peng Yu needed to know whether or not to set off for the next two stops. The Long March curators had decided to change the original plan to conclude at Yanan in October, and they declared an end to the first half of the project. Everyone knew that this meant an even greater challenge, and an even longer road. Lisa Horikawa, director of international communications and a Japanese-American, asked, “Does this mean I have to keep marching forever?”