Long March Project — Yang Shaobin Coal Mining Project

Field Research | Coal Mining Project

Yang Shaobin: Coal Mining Project

Time: 2004 – 2008

Artists: Yang Shaobin, Long March Project

Location:Hebei Province (Tangshan,Qinhuangdao), Shanxi Province (Changzhi,Shuozhou,Datong), Inner Mongolia (Baotou,Dongsheng)

Phase I | Yang Shaobin: 800 Meters Under

Yang Shaobin: Coal Mining Project

Time: Sep. 2 – Oct. 15, 2006

Location: Long March Space (formerly known as 25000 Cultural Transmission Center)

第二阶段|杨少斌:后视盲区

杨少斌:煤矿计划

时间:2008年9月4日至10月18日

地点:北京长征空间(前称二万五千里文化传播中心)

Observation | Excerpts from Yang Shaobin’s Notebook: A Textual Interpretation of “X-Blind Spot” by the Long March Writing Group

Yang Shaobin: Coal Mining Project

Time: 2009

Author: Long March Writing Group

Observation | Excerpts from Yang Shaobin’s Notebook: A Textual Interpretation of “X-Blind Spot” by the Long March Writing Group

Yang Shaobin: Coal Mining Project

Time: 2009

Author: Long March Writing Group

Yang Shaobin owns a black notebook. It’s a very plain notebook, the kind found in supermarkets or sidewalk stalls. It hasn’t been in use for long, and only one fifth of the pages have been written on. The cover appears worn, and pages protrude from inside. Ink and grease stain the title page. The notebook contains writings documenting Yang Shaobin’s two-year collaboration, from 2007 to 2008, with Long March Project on the development of the exhibition “X-Blind Spot”, and includes art proposals, work notes, and sketches that reveal in vivid detail Yang Shaobin’s feelings and thoughts as an artist. The following contains excerpts from this notebook in addition to certain details and key terms that should help describe, refine, and expand Yang Shaobin’s indelible network of memories. This network is like a thread that is woven throughout the artistic production of this project. Philosopher and theorist Gilles Deleuze speaks of the space between visibility and existence. This space or “interstice” is like a crevice that engenders something new. “X-Blind Spot” seizes this interstice, this psychological space, in the hope of continuously forming unprecedented links.

Key Terms: Losing One’s Way

Lu Jie, Xiao Xiong, Xiao Ma, Xiao Wang, and I departed from Long March Space in Beijing for the coal mines of Changzhi in Shanxi province to experience the life there. The journey by car was six hundred kilometers and took thirteen hours. Going along the Jingshi expressway, we all overlooked the fact that there was no interchange between the Jingshi expressway and Handan so we had to drive through the city of Handan before getting back onto the expressway. We didn’t stop to ask for directions until we got to Anyang, Henan province. Then we got on the Anlin expressway, switched expressways and were finally on our way to Changzhi. The road was bumpy and the car bottomed-out on several occasions. It rained along the way. By the time we arrived in Changzhi it was already eleven in the evening. The most aggravating aspect of the trip was the coal transport trucks. They drove recklessly and shone their headlights directly at oncoming vehicles. Changzhi is a small city. We eventually found a place to eat but it was filthy. The sesame paste on the floor looked like shit. The owner’s face was covered in scars. Disheartened, we returned to the hotel to rest after the meal.

– Yang Shaobin’s notebook, May 10, 2007

In 2003, when Yang Shaobin decided to collaborate with the Long March Project on an art project about coal mining, Chinese contemporary art was entering a period of rapid expansion. The practice of painting in China during this time differed from that of a few decades prior, when fieldwork and painting from life were emphasized. With the exception of government-sanctioned art, “realism” and its corresponding set of aesthetic values were increasingly inadequate means of expression in the face of a growing, money-hungry society. Like many artists today, commercially and academically successful contemporary artists prefer to work from private studios, looking to various texts and images as sources for their work. Yang Shaobin was equally caught up in this methodology; his technique, method, and design in the series of paintings commonly referred to as Red Violence (ongoing since 1998) and International Politics (ongoing since 2002) constituted and maintained a distinct style that was based primarily on texts and images. Such distinct elements became signature codes of his artistic practice and served as a safeguard and iconographic narrative, like that of many of his contemporaries, that catered to the pressures of satisfying a particular cultural identity within an international, market-driven platform.

But Yang Shaobin has never been one to settle for convention. His established working methods gradually began to eat away at his soul. He grew restless and started to examine and question the general direction of his work. For Yang Shaobin, the threadbare times of the “Yuanming Yuan era” were a strong yet distant memory. He had already shown internationally in prestigious exhibitions including the 48th Venice Biennale and was representative of the successful post-’89 generation, earning both academic and commercial acclaim.

Yang Shaobin and curator Lu Jie (founder and director of the Long March Project) met in the early 1990s during the Yuanming Yuan period. Lu Jie curated Yang Shaobin’s first exhibition in 1994 and had a hand in the artist’s initial commercial art transactions, subsequently inviting Yang Shaobin to contribute to the Long March Project in 2002 as one of over 250 participants from China and abroad. The Long March Project is a complex, multi-platform, international arts organization and ongoing independent art project whose programs variably focus on the relationship between art and social life, providing artists with the possibility of engaging in different contexts of production. From 2004 to 2008, Yang Shaobin and the Long March team made numerous visits to rural coalmines in Hebei, Northeastern China, as well as many other coal mining communities within this region. The group descended into mining shafts, experienced the life of local workers, and collected source material, culminating in the first phase of the project, 800 Meters Under, which was showcased as an exhibition in September 2006 at Long March Space. Various components of 800 Meters Under have since been exhibited in The Real Thing: Contemporary Art From China, Tate Liverpool, at the Sharjah Biennial, and other international exhibitions. Lu Jie said of the project, “we don’t look at the project as a matter of an artist creating works, but rather at its implications for contemporary Chinese history, culture, and social development; 800 Meters Under represents a textual documentation of the social responsibility and morality of art.” Perhaps such philosophical motivations of the Long March Project expressed a more practical significance for Yang Shaobin as an individual. Such provocative challenges have led to the continued in-depth collaboration between Yang Shaobin and the Long March Project, resulting in the second phase of the coal mine project, “X-Blind Spot”, produced between 2007 and 2008.

Key Terms: On Site

Excerpts from Yang Shaobin’s notebook, various dates

Shuozhou Antaibao Open-Pit Coal Mine:

Yan Menguan, sheep flock, dog.

Antaibao Open-pit coal mine. Overwhelming, imposing.

Changing room, close-up of shower room.

Work site: Excavator heaps coal onto KOMATSU 170

Winter scene. A very black and dirty road. The lens is focused on the road, capturing its changes. Record scenes at noon, record again at dusk. This way I can capture the temporal changes of the site, from lighting to atmosphere. In between the two shoots, take in-depth shots of another setting, like the open-pit coal mine or small-scale mine—best to get daytime and night-time shots for each.

Shuozhou Anjialing Open-Pit Coal Mine:

Dusk, overlooking a gigantic shaft. Changing room.

Inner Mongolia Project:

Confirm possibility of aerial shoot, airplane altitude: 200 meters; cruising altitude: 300 meters (limitations).

Jinnan Coal Mine: Shoot miner running very quickly, body, two feet. Stepping on ground covered in coal ash, create tense atmosphere.

Baotou: Record clouds, starry night sky, the ground during strong winds, record with microscopic approach, look for elements of movement, bleakness, helplessness, paltriness, the sewer (use above for scenes)—can find it anywhere.

Changzhi Sanyuan Coal Mine:

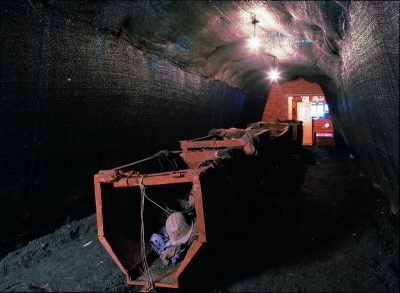

Shot of descending into shaft. (Light spot) moderate, indistinct . . . (cage) miners walking about. Tunnel is far and deep, flickering red light, enter work site, sound of machinery, noisy clamour. Partial light, oblong coal car in operation. A beam of light on the wall sways with movement of car. (Photograph by Lu Jie)

Swaying water, color: blue. A sunflower-like circular light flickering. A tunnel, the effect is pretty good. Black water bubbles . . .

Work site: Miner’s face, a beam of light hits his face, it’s very bright. Digital numbers flickering, light shining on machinery, swaying. The work site of the miners is very good.

A miner doesn’t look directly into the camera, not bad. Miners examining and repairing facilities, sound of people talking, pretty good!

Coal miners shoveling coal, can use.

Sound of some of the miners interacting at work site, can use.

Conveyor belt, momentum, add sound.

Coal mining machine in operation, good sound.

Shot connecting to ground level, only dimly discernible, light circle, add sound.

Sound of our camera crew walking back.

Electronic sign showing human figure.

Shot ascending from shaft. Passing over group of miners below.

Miners ascending from the cage.

Datong Wuguan Village mine:

Slum, dead cat, indoor setting.

Miner making a phone call. Miner ascending from shaft in the dark.

Security check and awaiting security check.

Jade green ceiling light reflected on miner’s face, getting shower voucher.

Fushun open-pit coal mine:

Very empty scene. Pollution. Coal mountain waterfall.

Mud, black water stream.

Tangshan small-scale coal mine:

Shot of coal being poured in room. Entire shoot took three minutes, sufficient usable shots. Numbers visible, can be linked with dripping sound of hospital cardiogram. Cut back and forth between shaft entry and shaft entry of large mine. A miner operating in a high altitude, can link with scene of doctor performing lung lavage. Link image of hospital cardiogram with sound of migrant workers smashing roof. Water in the room, a sketch in the water. Wall reflected in water. Legless man walking in hutong, standing before a shaft.

Link ruins of destroyed building with Baotou coal mine.

Smoke and dust inside room, insects. Two auto mechanics, partial tire.

Shot of tearing down building in the evening. Ruins under light, sound of breaking glass.

Baotou Yanggeleng:

Shower. Miners ascending from shaft, a few miners moving about. . . .

Close-up of miner, hurrying along the road. . . .

Baotou Steel: smoke, dense smoke, cooling off water, icicle.

Large-scale coal factory. Miners unloading coal from the top of train car.

A long series of train cars. People look really small, many people.

Dongsheng small-scale coal mine:

Four-wheeler moving back and forth from inclined shaft. Light getting brighter from a distance, can link with close-up of patient’s neck breathing in hospital room. Sun setting, coal mountain combusting.

— Yang Shaobin's two-year director's notes

Compared with “800 Meters Under”, the sites observed for “X-Blind Spot” were more varied and covered more territory, including the four diverse coal mining districts of Shanxi, Hebei, Inner Mongolia, and Liaoning. The Shanxi Shuozhou Antaibao open-pit coalmine is visually arresting and difficult to describe to someone who has not see it with his or her own eyes. It is vast and far-reaching, like an excavation site on a terrestrial pole. The sky and earth are one colour, and there is nothing but boundless expanse for as far as the eye can see, like the surface of the moon. Even the gigantic excavators and transporters are dwarfed. The Komatsu 170 is a gigantic piece of machinery used to transport coal in outdoor environments. Its wheels are over two meters in diameter. The name “Blind Spot” is inspired by the fact that there are fifty- and sixty-meter blind spots in front of and behind the machine, respectively. The physical repercussions of such blindness, a technical consequence, lie in stark contrast to the immensity of this mining environment and to the visible risk of labour. Confronting such realities, Yang Shaobin and the Long March team responded to this vast social landscape, to its tangible and metaphysical elements, and attempted to reconcile this grand narrative of China’s industrialism with the reality of its repercussions.

Key Terms: Miner, Mine Supervisors, Contemporary Artist

Ate breakfast at ten in the morning and discussed program. Lu Jie’s friend, Yang Mou, a coalmine supervisor, arrived at the hotel to meet with us. We discussed coalmine matters. At eleven, we drove with Yang to the Sanyuan Coal Mine, about twenty minutes from the city, to have lunch with the president of the mine and other leaders. It reminded me of the first time I went to the mine in Tangshan. After lunch, Xiao Wang, Xiao Ma, and myself retrieved the camera equipment from the car. Lu Jie and the coalmine president chatted. Xiao Xiong recorded this interaction.

We went to the supervisor changing room to change into clothes for going down the shaft. A security officer accompanied us into the shaft, which was three hundred meters deep. We were down in a few seconds. It was very clean inside and we rode a small mine car into the tunnel . . . the trip went smoothly. When we entered the work site, miners were examining and repairing equipment and turned on the machinery just for us. We set up the cameras to record from two different angles. We turned off the flash on the camera in order to avoid explosions. We ascended the shaft two hours later. We recorded everything on tape. In the evening, Lu Jie’s friend arranged a dinner. We drank a lot and played drinking games. Seven people drank five bottles of 35-year Fenjiu (a spirit distilled from sorghum).

–Yang Shaobin’s notebook , May 11, 2007

When we arrived at the sealed-off small-scale mine, a few miners were working and an elderly person was standing guard at the mountain. Wei Zong drove toward a legal open-pit coal mine. The workers halted their entire operation when they saw us coming because they were scared. I didn’t understand. They resumed work once we left.

We went to the television station with general manager Yang to look for information about coal mine disasters and small-scale mines. Earlier, the director had promised to provide us with some materials. However, we realized we couldn’t use any of the information he gave us. General manager Yang was very displeased. I felt helpless because it was [politically] sensitive information.

–Yang Shaobin’s notebook, May 14 and October 4, 2007

“X- Blind Spot” employed video, installation, sculpture, photography, and other forms of media, and this multifaceted use of material was as complex as the obstacles Yang Shaobin confronted throughout the project. One particular obstacle of note was the lack of cooperation from the many small-scale mine directors and television stations. Their hesitancy and suspicion reflected a recurring problem Yang Shaobin encountered in his research: the awkwardness of how his identity was perceived. Previously, the Long March team often encountered situations in which it was difficult to find an appropriate way of introducing Yang Shaobin to local mine workers. Sometimes they said his paintings were very valuable, fetching upwards of a million renminbi apiece. Yet, it was the fact that he arrived from Beijing that often caught people’s attention. “From Beijing” invariably carried more political and authoritative clout than “contemporary artist.” On the other hand, Yang Shaobin’s identity as a contemporary artist was similarly at risk of being misunderstood by local artists. Currently, in the Chinese art world, with a handful of major cities the exception, most artists still practice traditional ink brush painting and create works that have a government-approved slant. While these were intangible differences, they existed nonetheless.

The contemporary artist could be argued to be an elite cultural product. The awkwardness of Yang Shaobin’s perceived social distinction and wealth in some ways epitomized the reputation of contemporary art in China today. In this way, projects like “800 Meters Under” and “X-Blind Spot” enable us to reflect and challenge that status. “800 Meters Under” takes modernization, Westernization, industrialization, nationalism, and collectivism as its backdrop and focuses on the difference between the state of human existence in state-operated mines (e.g., Kailuan coal mine) and those of illegal small-scale operations (e.g., Heiliang coal mine). “X-Blind Spot”, on the other hand, departs from the depths of the underground to focus on open-pit coal mines and uses a multidisciplinary approach that incorporates humanities, geography, and economics to examine various aspects of coal production in the northern provinces. During the two-year period observing dozens of coal mines and communities, Yang Shaobin became familiar with coal mine leaders at all levels, from large state-operated supervisors, mid-size to small-size mine supervisors, household coal pits and their related facilities, contractors hired to tear down buildings, miners, local culture cadres, and artists. He witnessed the surreal scenes of high-tech, large-scale work sites, but also the microscopic and intimately human backdrops of coalmines as they relate to migrant workers, urbanization, education, environment, and so forth. Acknowledging this reality in hindsight is tracing a kind of history; it is linking the past with the present. The concept of a “blind spot” is a warning, a question, a challenge, and a testimony that draws 360-degree attention to the lifestyle of a particular social group that revolves around coal drawn up from the depths of darkness; it is the space between old man Zhang, a local sheep herder, and his journey from Inner Mongolia, and a sentry for a small-scale open-pit coal mine in Datong, or Li Jianguo, a model worker who deftly operates a nearly six meter high Komatsu 170 for the Shuozhou Antaibao coal mine.

An important difference between this coal mining project and a straightforward work of art conceived and produced in an artist’s studio is the far more fulfilling and multi-dimensional interaction with social reality that it involves. For an artist like Yang Shaobin, who comes from a studio and text-based practice, what he confronts is not only the subject of his research, but the entirety of real life—eating and drinking with leaders of local coal mines, manoeuvring through various social relations, befriending miners, etc.—all these details were crucial for the completion of the project. This experience may not be so dissimilar to that of the early art collectives in China that were also driven by social concerns, and it necessarily challenges the elite mindset and assumed language of the contemporary artist. Here, we see an artist’s foundations altered and reconstructed before a multifaceted reality. The artist that returns to the studio from this experience is invariably affected, and this effect will continue to transform and subtly permeate his work.

Key term: Work Site

Shot of descending shaft. (Light spot) moderate, indistinct . . . (cage) miners moving. Tunnel is far and deep, red light flickering, entering work site, sound of machinery, noisy clamour. Partial light, oblong coal car in operation. A beam of light on the wall sways with movement of car.

Miners examining and fixing facilities, sound of talking.

Miners shoveling coal.

Sound from interaction between some of the miners at work site.

Conveyor belt, momentum, sound.

Coal mining machinery in operation.

Shot of connecting to ground level, very dim, light circle.

Sound of our camera crew walking back.

Digital sign showing human figure.

Shot ascending from shaft. Passing over group of miners.

Miners ascending from the cage.”

–Yang Shaobin’s notebook, various dates

There is a different work site we seldom witness: the studio and the life of a contemporary artist within it, which are frequently overshadowed by exhibition openings, the marketplace, and media. The Long March team witnessed Yang Shaobin’s sincerity, rigidity, and pain. Each stage of creation was a risk, atranscendence. What unfolded in “X-Blind Spot” was years of painstaking thought, putting into practice one’s beliefs, and the undertaking of a massive workload. For several years, the Long March team and Yang Shaobin endured a joint purgatory of which the most painful portion was succeeding in making breakthroughs in the understanding and creation of art. The conversation and work at Yang Shaobin’s new studio in the 798 Art District, his studio in Songzhuang, and at Long March Space revolved around and progressed from the meaning of brutality.

Key Term: Brutality

. . . continuing onward, renovating road ahead, entering worker housing area. It reminded me of the circumstances I grew up around. Miners and families sat in the hutong entryway chatting, playing chess.

I still like the feeling of desolation and brutality. I have to try my best to get shots of this scene. I saw scenes like this in the Datong area . . .

– Yang Shaobin’s notebook, video notes, various dates

Forty-five-year-old Yang Shaobin has profound memories of growing up in the coal mine of Hebei Kailuan. His parents also hail from mining areas in China. After graduating from art school in 1983, he returned to the coal mine to become a police officer. His entire life was intimately linked with coal mines prior to his becoming an independent artist in Beijing at the age of 28. This life experience undoubtedly had a deep influence on Yang Shaobin’s work and thoughts. It is also directly responsible for the fruition of projects like “800 Meters Under and “X-Blind Spot.

Yang Shaobin’s life in the Yuanming Yuan artist village during the 1990s could be considered brutal. At times, there wasn’t even enough to eat. Artistic creation sustained him through the suffering and hardships of life. Like many literary writers and artistic youth of the time, Yang Shaobin took Irving Stone’s writing on Vincent Van Gogh in Lust for Life and William Somerset Maugham’s writing on Paul Gauguin in The Moon and Sixpence as his bibles. In media interviews frequently mentioned incident that occurred during this period was the time police broke open his door in the middle of the night to check his temporary residency permit. These examples illustrate elements of violence or brutality in his life that can be linked to his earlier series of paintings, Red Violence, and even a more recent series, International Politics. While his painterly expression in these series remains unchanged, the focal point has already shifted. The deconstructed and spatially dislocated blurry human figures in the Red Violence series represent an objectification of Yang Shaobin’s psyche and feelings, while the real or fictionalized historic scenes depicted in the International Politics series represent a construction of his external perspective. Together, the series complete a shift from his inner self to his outer self, from the personal to the fictional. In Yang Shaobin’s own words, art provided him with a release, and the thing that was released may very well have been what Antonin Artaud refers to as totalizing fear and devastation.

Key Terms: Tearing Down the Slums

Drove to the southern part of Datong, the roads were very bad. It was filthy the entire way, with lots of raised dust. In summer, the humid air does not appear dirty. All the way to Penghu District . . . strip after strip of rundown hutong . . . I shot for about forty minutes in the hutong. Afterwards, I went outside, took some footage of people breaking reinforced steel bars amidst the ruins of torn down buildings. Then I went to the roof of the building and took a crane shot of the entire scene . . . drove to Nanjiao at ten in the evening, shot scene of buildings being torn down.

– Yang Shaobin’s notebook, October 4-5, 2007

“The law is a calculated and relentless pleasure, delight in the promised blood, which permits the perpetual instigation of new dominations and the staging of meticulously repeated scenes of violence.”

– Michel Foucault

Many of China’s mining districts contain large slums. Some miners end up living for over a decade, in some cases even one or two generations, in buildings originally meant as temporary and crude housing. The destruction of slum communities directly affects the livelihoods of miners and is usually spurred by the exhaustion of resources and the continuous shift of worker peasant status as they move from farmer to miner to farmer again. When their homes (slums) are destroyed, many revert back to working the land. Yang Shaobin portrays this phenomenon with a humanitarian eye, looking through the video lens, along the length of his brush, and reflecting on issues of migration, identity, and social status. Urbanization and shifting identities are also themes of ‘Translocalmotion’, the 7th Shanghai Biennale (2008), of which the video portion of “X-Blind Spot” was a part.

Key Term: Washed-out Sediment

Beidaihe Lung Lavage Hospital.

Patients of lung lavage treatment show the sediment that is washed (from the lungs?). Hospital room attendant, heart rate monitor, close-up of person’s face. Close-up of different parts of the body, close-up of IV bottle filled with gurgling liquid, close-up of general scene, green liquid. Neck breathing, close-up, underside of bed.

Lung specimen.

Operating room. The entire process, close-up of IV bottle. Doctor making notes on status of operation, changing tube, close-up of machinery (inserting tube), close-up of sediment being washed out, see patient’s face. Over twenty bottles of sediment.

Close-up of doctor, pressing respirator.

Shot of the sea.

– Yang Shaobin’s notebook, video notes, various dates

The location is Hebei province, Qinhuangdao Beidaihe Black Lung Disease Rehabilitation Center (“X-Blind Spot” research site). According to some sources, 440,000 people in China currently suffer from black lung disease. There are an estimated 600,000 more undiagnosed cases, of which 46% are miners. Black lung disease is a deadly respiratory illness for which there is currently no cure. Lung lavage remains the most effective treatment. The artist and the Long March Project visited the hospital to observe the life-threatening predicaments miners confront.

These scenes are incorporated into Yang Shaobin’s videos and paintings. In his paintings are the IV drips, physical examinations, the black liquid that is washed out from the lungs, and the exposed, diseased lung tissue—all of this stands in for the figures of the miners. The miners themselves are no longer the focal point; they have departed or are “hidden” from view. In the process of this shift, Yang Shaobin alienates our understanding of what constitutes a coal miner, posing questions about human labour and human neglect in the face of economic advancements.

Key Terms: Black and White

Coal miner, black person, black bird, black flower, black car, black shoe, black building, black hat, black feet, black hands, black sky, black fingernail, black tire, black tooth, black chimney.

– Yang Shaobin’s notebook, sketch notes, various dates

Unlike the blackness in the first phase of the coal mine project, 800 Meters Under, a fundamental aspect of X-Blind Spot is the contrast between black and white—like the over-exposed black of x-ray scans. It is an inverse vision, forced retrospection, introspection, piercing lucidity, distinct blind spot, reversed double-sided displacement, and flashback. What we see now is white—a miner’s presence in absence. All is severed; all is reformatted through media and imagery.

Key Terms: Chaplin and Guevara

Put a potholing Chaplin in the picture or use existing shot of small-scale mine to compose a work (large painting).

–Yang Shaobin’s notebook, sketch notes, date not given

In 2004, Yang Shaobin painted a small-scale portrait of literary theorist and cultural critic Edward Said. Yang Shaobin used his typical deconstructive painting style to construct a “destroyed” image of the academic. The work was called Edward Said. The artist has actually painted many similar subjects using the same technique, including some renowned politicians and even himself. But most of these pieces tend to be nameless, Untitled. This naming process reflects a desire to maintain a vacuum-like state that can be likened to an artist’s resistance to interpretation. Yang Shaobin’s fundamental attitude is respecting the value judgment of the painting itself.

In the “X-Blind Spot” series, there is a scene with Charlie Chaplin and what appears to be the corpse of a miner who looks like Che Guevara. The appearance of the two figures may seem random at first, but, upon further analysis, viewers will discover that they actually serve as a code. Yang Shaobin depicts Chaplin as a symbol of early shovel-and-pick industrialization, similar to his characters in Modern Times and other films. In the painting, Chaplin digs earnestly in an act that resembles rowing a boat, except he is in fact positioned on a bed, calling to mind the miners who row their carriages below ground only to end up contained within another metal frame, their lungs in need of cleansing. Perhaps we can interpret the image as a symbol of post-industrialization and also appreciate the sense of humour that serves to mitigate the sombreness of the subject matter. The Guevara figure challenges issues of revolutionary heroism and death. All of this corresponds to the artistic idealism inherent in “X-Blind Spot”, the notion of artist as elite cultural product being sent to work, to experience labour in one of the harshest of environments where risk, danger and brutality are an everyday reality. Yang Shaobin’s works in “X-Blind Spot” urge viewers to self-reflect, reassess, and preserve those moral and ethical values that are constantly fragmented in contemporary daily life, to transcend potential blind spots, to be aware of existing networks and the possibility that such networks need reassembling. This is the enlightened message that the collaborative coal mining project between Yang Shaobin and the Long March Project presents.

On modernity, Anthony Giddens wrote: “The juggernaut [is] a runaway engine of enormous power which, collectively as human beings, we can drive to some extent but which also threatens to rush out of our control and which could rend itself asunder.”

Can we tame the juggernaut of modernity or at least guide and reduce its risks to increase its opportunities?

Translated by Philana Woo