Long March – A Walking Visual Display

作品《难民共和国》展在原中华苏维埃中央临时政府前展出-2-400x300.jpg)

Site 1: Ruijin, Jiangxi Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Jun. 28 – Jul. 7, 2002

Site 2: Jinggangshan, Jiangxi Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Jul. 8 – Jul. 12, 2002

Site 3: Daozhong, Guangxi Autonomous Region

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Jul. 13 – Jul. 18, 2002

Site 4: Kunming, Yunnan Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Jul. 21 – Jul.22, Aug. 2 – Aug.5, 2002

Site 5: Lijiang, Yunnan Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Jul. 23 – Jul. 27, 2002

Jul. 31 –Aug.01,2002

Site 6: Lugu Lake, Yunnan/Sichuan Provinces

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Jul. 27 – Jul. 30, 2002

Site 7: On the Train between Kunming and Zunyi

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Aug. 6, 2002

Site 8: Zunyi, Guizhou Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Aug. 7 – Aug. 12, 2002

Site 9: Maotai, Guizhou Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Aug. 13 – Aug. 15, 2002

Site 10: Xichang Long March Satelite Station, Sichuan Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Aug. 16 – Aug. 21

Site 11: Moxi, Sichuan Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Aug. 22 – Aug. 27, 2002

Site 12: From Anshunchang to Luding Bridge

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Aug. 28 – Sep. 1, 2002

Works made along the Long March

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: 2002

Artists: Qu Guangci, Qiu Zhenzhong, Song Dong, Yin Xiuzhen, Wang Bo, Qin Ga, Qiu Zhijie, Ingo Günther, Jiang Jie, Wang Jingsong, Yao Ruizhong, Shao Yinong, Mu Chen, Xiao Lu, Shen Meng, Xiao Xiong, Ding Jie

Site 11: Moxi, Sichuan Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Aug. 22 – Aug. 27, 2002

Curatorial Plan: Dissemination and indoctrination – the displacement and juxtaposition of object and reason, secularism and religion

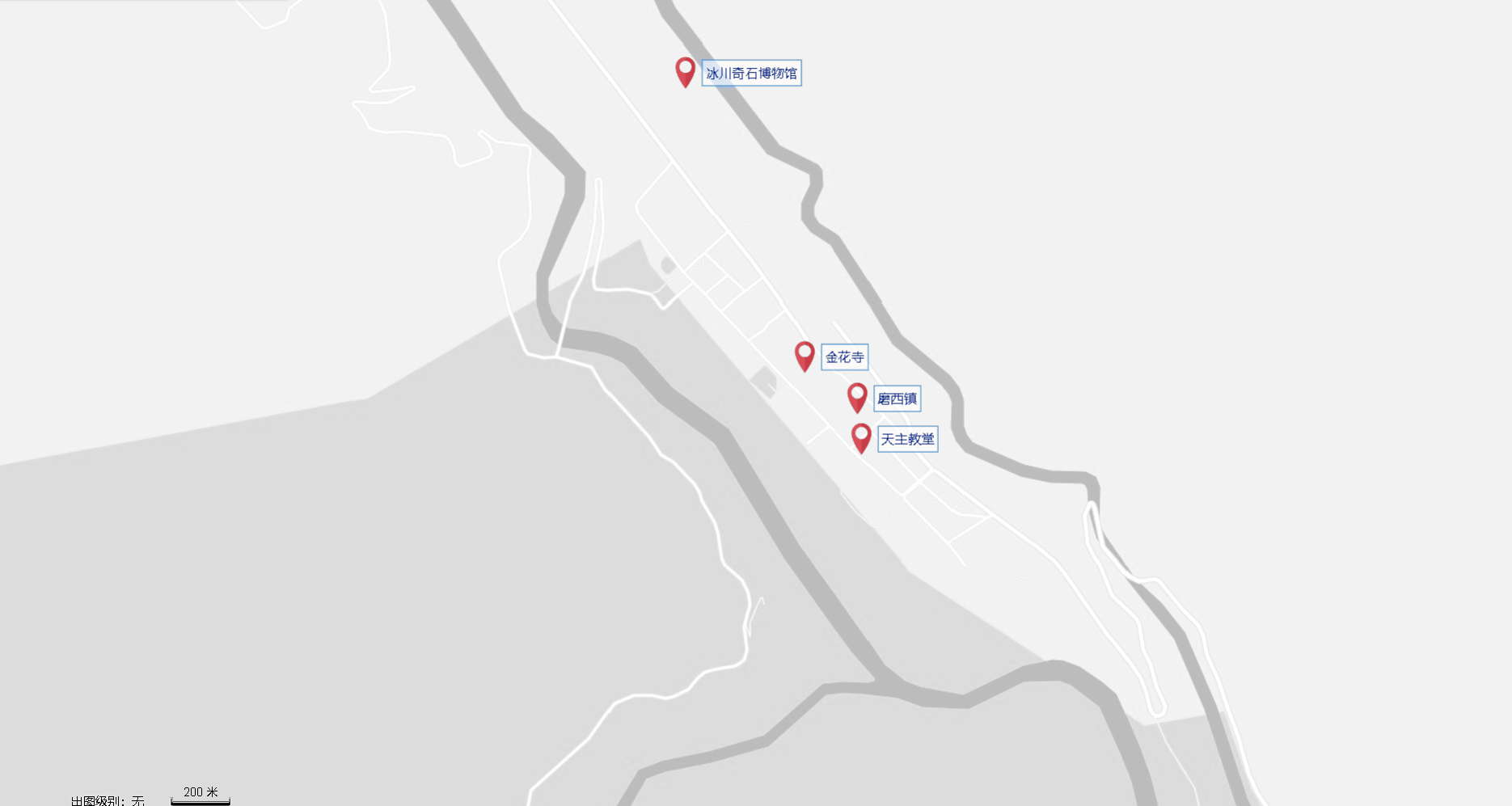

Route: Moxi, Sichuan Province

Time: 2002.8.22-8.27

August 22 – 23 Xichang - Moxi, Sichuan Province

Yao Jui-chong, Turning the World Upside-Down, photography

Xiao Honggang and Jiang Jie's "Baby"

Shi Qing, The Great Flood, performance

August 22. For the previous few days, the biggest concern occupying Road Manager Yang Jie, aside from treating everyone’s illnesses, was how to take care of transportation away from Xichang. The destination was Moxi County, alongside the Dadu River, beneath Gongga Mountain, atop Hailuo Ravine. The 200-plus kilometer trip lasted more than ten hours.

At dinner, Lu Jie introduced an idea that startled everyone: the Long March should stop and rest for three or four weeks. The Long March website, headquartered in Beijing, was already a month behind the actual progress of the March. Busy all day with implementing projects, he and Qiu Zhijie had no time or endurance to write reports each night. In a project like the Long March, realizing projects and publicizing projects were equally important. Furthermore, how should they view the preparatory work for the project, or the connection between the curatorial concept and its implementation on site? What was the relationship between planning and implementation? This they must stop and think about. Everyone had sensed that Lu Jie’s scholarly thinking and on-site implementation were drastically different, and that he had grown more and more silent with each passing day. Yao Jui-Chung asked in Fujianese if building something up was not precisely for the sake of knocking it down. Lu Jie responded in Mandarin that these were the same, indivisible. Qiu Zhijie thought that a week was enough to supplement and edit the website, but that even three weeks was not nearly enough to insure the quality of the works to be realized in the remaining sites. The discussion ended without a conclusion. Everyone was dazzled by the beautiful nighttime colors of Shimian. They walked slowly back to the hotel along the bank of the Dadu River.

August 23. Yang Jie called for five three-wheeled carts, which were not even enough for the Marchers and their luggage. They occupied eight carts in the end, mightily crossing the Shimian Great Bridge, and boarding a bus on the other side of the Dadu River. This road led directly to Luding. When the Red Army was making this same trek in 1935, they traveled along the east bank of this river on the way to Luding, led by Liu Bocheng and Nie Rongzheng.

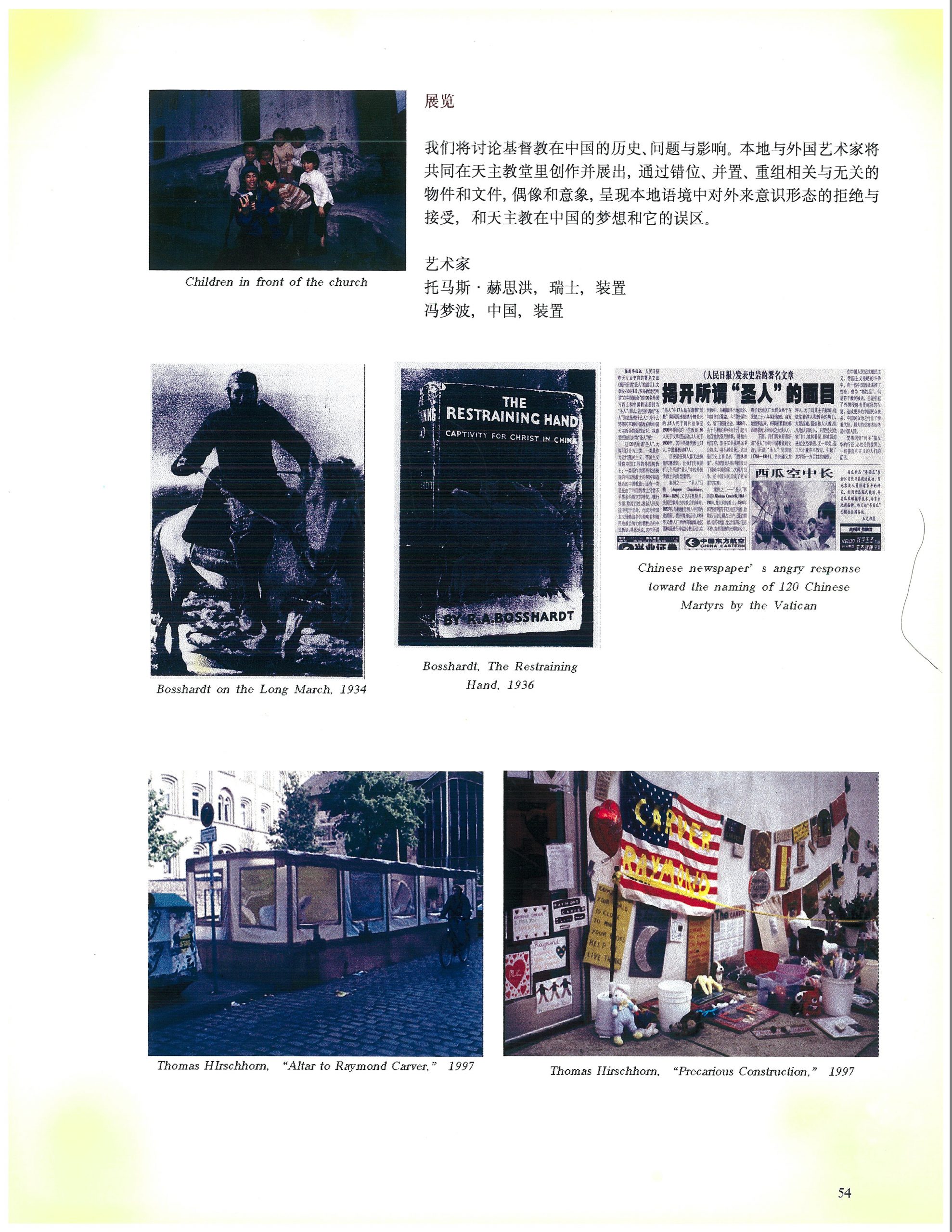

At noon, the bus turned left at Rainbow Bridge, leaving the west bank of the Dadu River. After thirty minutes of moving among steep precipices and bottomless cliffs, the bus entered Moxi county. The attendants behind the counter of the Long March Hotel were all dressed in Red Army uniforms, and the lobby walls bore Mao’s poem “Long March” and portraits of Mao, Deng Xiaoping, and Jiang Zemin, which had been blown up on a computer. Next door to the hotel was the Long March Supermarket. Further in was the Hailuo Gorge glacial forest of Gongga Mountain, a snowy mountaintop veiled in clouds. The town of Moxi was on a mountain ridge. On May 28, 1935, Mao Zedong and Zhu De made their headquarters in Moxi for a night, holding the Moxi Conference. When they lodged in a Catholic church, Chen Changfeng, one of Mao’s bodyguards, ate Western food for the first time in his life.

At midday, the televisions in the tiny hotel were broadcasting a series about the Long March. Several days earlier, Beijing artist Shi Qing and his assistants had arrived in Moxi, looking to prepare his work. The curators made a lap of the town with Shi Qing, who was already quite familiar with the situation. His installation/performance work The Great Flood would unfold along a north-south axis from Jinhua Temple to the Catholic church. The installation portion of the work was nearly completed on the roof of an unfinished building.

There are many churches along the route of the Long March, and the Red Army liked to turn churches into their temporary headquarters. Was this out of enmity for imperialist culture? Was it because churches were especially clean? Or was it because of the allure of churches as visual spaces? In the Chinese hinterland, earnest missionaries once worked with all the devotion of the Long Marchers, making a massive trek, passing their beliefs onto people, using medicine to save the poor, trying all the while to subvert the natural order of things. In these mountainous villages, they built countless structures to symbolize the heavenly kingdom, and the church in Moxi was one of these. The Long March would use this as a site to explore the transmission and indoctrination of Christianity, a foreign idea, among Chinese.

Yao Jui-chong, Turning the World Upside-Down, photography

That afternoon, Yao Jui-Chung photographed himself upside down in front of the Catholic church, as Qiu Zhijie and Shi Qing visited Bishop Li of the Luding Diocese, Moxi nun Wei Fang, and others. Wei Fang lived in the very room that had once accommodated Zhu De, the priest who had come especially from Kangding to meet with the Long March ranks.

When asked about the similarities between the Red Army and Christianity, Bishop Li answered point for point. A few years prior, trying to verify the authenticity of the “flying war over Luding Bridge” story, he spent a few days walking the route from Anshunchang to Luding along the bank of the Dadu River. “It is possible,” he asserted. As to whether he believed that a “Moxi Conference” had taken place in this church, Li was more skeptical. In the materials he had read, at least, there was no direct mention of it. After graduation from the seminary, Li was sent by the church to be the general priest in charge of the entire Kangding area. The locals call him bishop, and he carries himself in a stubborn and diligent manner.

Xiao Honggang and Jiang Jie’s “Baby”

Lu Jie and Qiu Zhijie worked until sunrise before sleeping, and just after 9:00, they were awoken by a knock on the door.

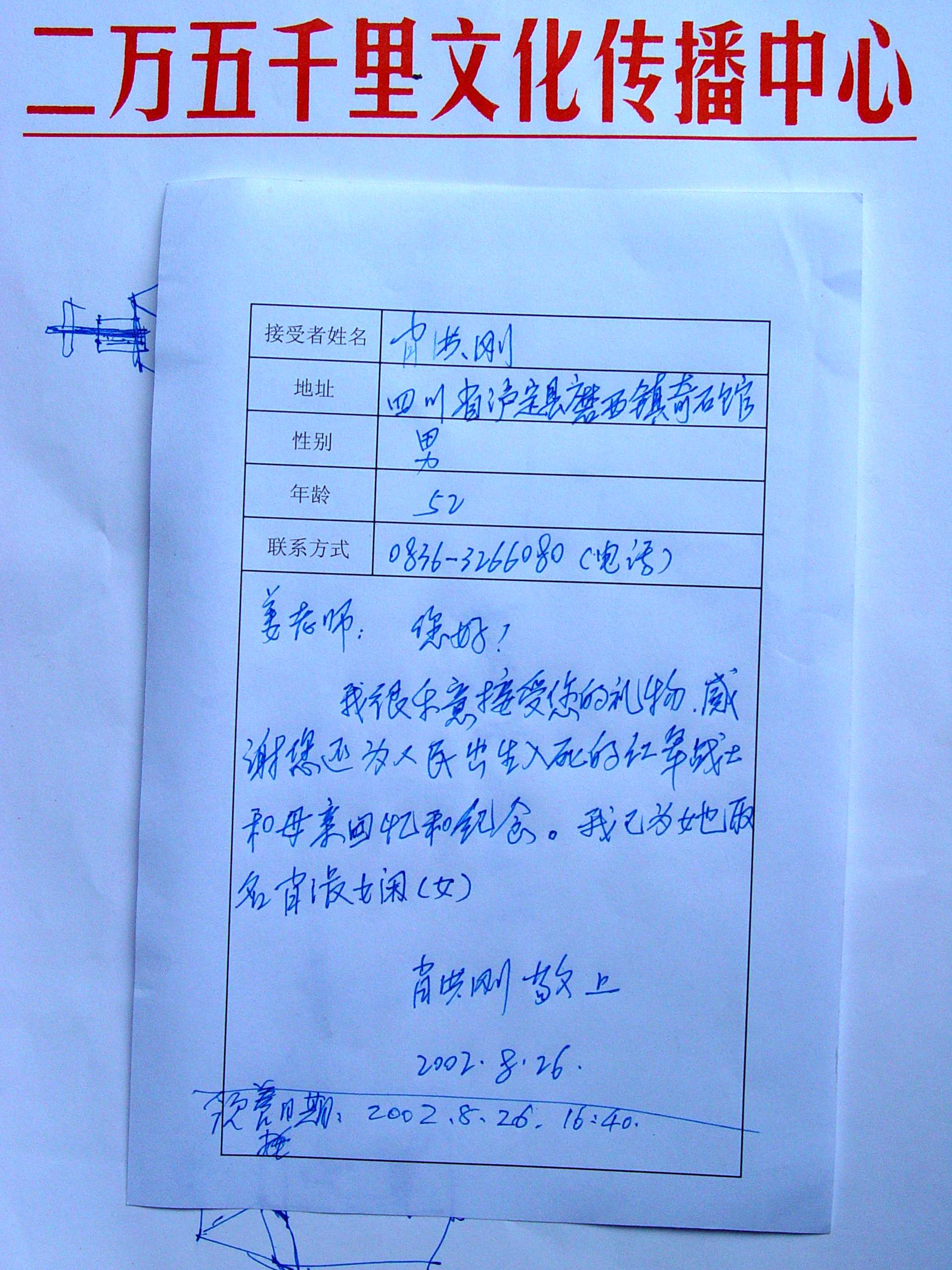

A stranger stood at the door, calling himself Xiao Honggang. He had opened a “Glacier Museum of Strange Rocks” in Moxi, and he chattered away about how the Long March contingent needed to go and pay a visit. He said he was a collector of strange rocks, and had specimens from every nearby ravine. He knew of some places that were much more beautiful than Hailuo Ravine, and he wanted to take everyone to see. Finally after the man went away, they burst out together, “It’s him!” They had thought of giving him Jiang Jie’s baby.

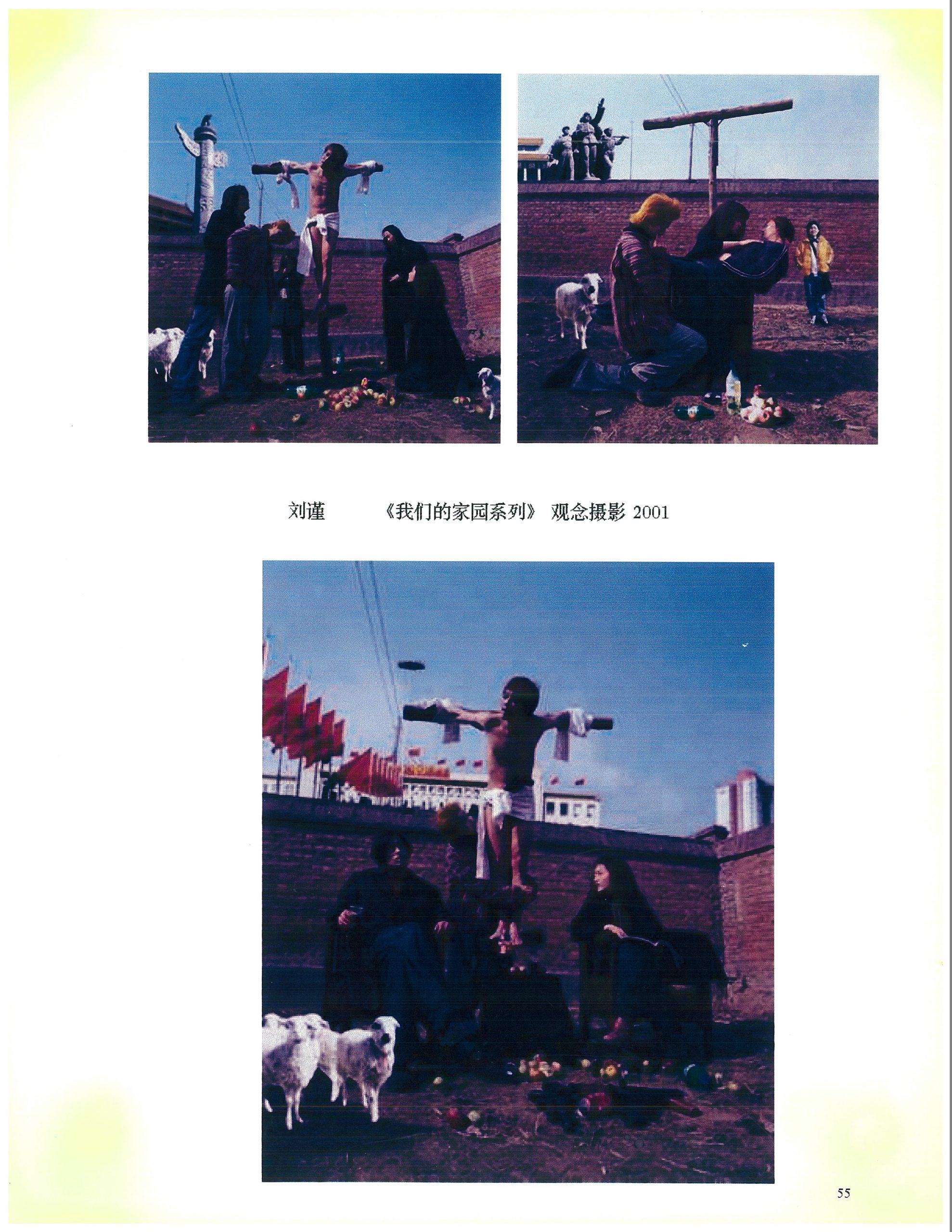

Jiang Jie, Sending off the Red Army: In Commemoration of the Mothers on the Long March, sculpture/performance

Everybody sat down. Xiao Honggang’s Bai ethnicity wife brought out the tender boiled corn and everyone began to eat, gnawing at the cobs and talking at the same time. The Xiao family’s three children stood around the group listening. The conversation started about the children, and how in accordance with local population control regulations, a primary school teacher like Xiao who married an ethnic minority woman could have three children, one boy and two girls. But what Xiao really wanted to talk about was his rare stone, so we talked about rare stones.

“Are those rocks all your works?” “Yes”

“So you just gave them all names?”

“Yeah”

“In the West, often the person who names the child is that child’s godfather. Are these stones also your children?”

Old Xiao laughed honestly and said he really does feel that way. We began to talk about how by giving these naturally formed strange stones a name they are turned into abstract sculptures, we talked about realist sculpture and from there it was only logical that the conversation turned to opening up the box full of Jiang Jie’s sculptures. Qiu Zhijie began to explain the ideas behind Jiang Jie’s works to the Xiao family.

“I’ll give one of [the sculptures] to you to look after as a child.” Old Xiao’s eyes flashed with happiness. We said that “We all came here to give it a name”. An old man was sitting off to one side, He’s Xiao’s neighbor and is also a primary school teacher. Until then he hadn’t said a word but at that point slowly but confidently said: “Name it Shuxian”. From that moment, Jiang Jie’s doll sculpture became the fourth child in Xiao Honggang’s family and was given the family surname: Xiao Shuxian. Xiao Honggang drafted out a receipt form to give to Jiang Jie. The entire family came together to embrace the doll and take a family portrait by the front door. Xiao Honggang carefully opened up the glass cabinet and delicately placed the doll on a shelf with other valuable objects. When we left the house, we told Xiao Honggang “We’ll be back to visit her”. We were already on our way when Xiao Honggang called out for us to come back, holding in his hands some trumpet shells from the Hailuogou Glacier giving one to each of us “Long Marchers”. “I was afraid you wouldn’t have space for the bigger shells, these here are as a souvenir. The next time you go to Hailuogou, come and visit us for a few day”

“Of course we’ll be back”, we said, “we’re all relatives now”.

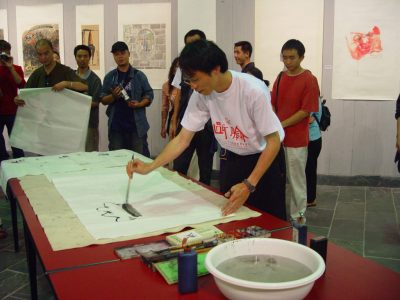

Jinhua Temple is in the center of Moxi, on the oldest street, two hundred meters north of the Catholic church which must have marked the south end of town in earlier times. The simple temple is four stories high, with a stele on each floor. The first floor has a horizontal stele discussing “law comes from religion.” The second floor has a vertical stele on Jinhua temple. The third floor stele declares the room “Jade Emperor Pavilion.” The fourth floor is engraved “Palace without limits,” and on the left side of this stele there is a high-pitched horn. The small stone lions outside the entrance sat on round pedestals. The right wall was inscribed “Warmly Welcome the Reading of Scripture for Prayer and Repentance; Celebrate the Birthday of the River Deity.” The concepts were fundamentally Daoist, mixed with a bit of Buddhism and the local religion of the Jinhua Spirit. The first floor was devoted to the Jinhua Spirits, the left to the Erlang Spirit, the right to the “River King,” with a statue to the god of fortune thrown in. In Chinese villages one can often see strangely intermingled beliefs, and this was another example.

Across from Jinhua Temple was a stage, which according to Uncle Yuan, had not been repaired in three hundred years. The space between the temple and the stage could become an amphitheater capable of holding several hundred people.

Uncle Yuan’s real name was Yuan Gongchun, and he was in charge of Moxi’s “Setting Sun Red Elderly People’s Club.” The local government had granted his organization use of this decrepit stage as a site for their activities. He made his job vivid and dramatic. In effect, the management of Jinhua Temple was also that of the Elderly People’s, as the temple didn’t have any dedicated monks, Uncle Yuan was in charge of that too. Uncle Yuan was exceptionally supportive of the Long March, so it was agreed that the Elderly People’s Club’s stage would be changed into a space for foreign religion, and would stand in comparison to the local religion manifest in Jinhua Temple. They would set up Wim Delvoye’s X-Ray stained glass windows, along with pictures by Liu Dahong and Liu Jing, and Sui Jianguo’s Mao Suit Jesus, arranging these in the style of a Christian altar. Uncle Yuan agreed to organize a Elderly People’s Club performance of the rewritten revolutionary songs to be filmed by the Long March camera crew. That night, they could project in the theater some videos about the Taiping and Boxer Rebellion and discuss them with the locals as per the curatorial plan. They settled on doing this on the 27th, and Shi Qing’s performance would continue to unfold throughout the entire process.

Everyone climbed the Jinhua Temple stage with Uncle Yuan, where a group of old women were dancing. On yellowing pieces of paper hung from the walls were the lyrics to songs written by members of the club to the tune of famous revolutionary songs. “Nanniwan” had been changed into “Sing Hailuo Ravine,” and rhymed in Chinese: Gongga Mountain/who fears your ten thousand high soldiers/the workers who built the highway were made of iron/with determination sharp as steel/they wanted to finish that highway/to run it up the glacier/a cement road, flat and wide/a cement road flat and wide/cars moving all along the road/coming and going busily/if you want to take a large car, take a large car/if you want to take a small car, take a small car/this is already not an old city/it has become a little Hong Kong!”

The revolutionary song “Climb the Mountain” had been changed into “Supernatural Moxi”: “This is a place for travel/this is the place I was born and raised°/This is an open place/A place were guests can come to rest/On this stretch of open land/We depend of the Party’s bright and clear leadership.” Some sentences were not beautiful at all, but the local charm had clearly expressed itself on the page.

Wim Delvoye, The Chapel Series, photography

August 27 was the most important of the Long March’s days in Moxi, with many important activities scheduled to take place simultaneously.

Seven of Sui Jianguo’s Mao Suit Jesus sculptures had been hung in a straight line across the front of the stage, reflecting the importance of the number seven in many different religious traditions: the seven days of the Christian creation myth; the seven treasures of the Buddhist cycle; the seven branches of Zen; the seven fairies in Chinese traditional mythology.

Another small Jesus sculpture was placed in the precise center of the stage podium, atop a traditional window design that represented fortune and longevity. Hung along with Liu Dahong’s Altar and Liu Jin’s photographic series My Spirit Park, the works transformed a traditional Chinese stage into something resembling a Christian church. The Jesus icon merged into the window design, and the traditional temple architecture merged with the stained glass windows. These visual phenomena might be easily construed as classic instances of the postmodern pastiche so common to contemporary art. But as far as the Long Marchers were concerned, there was nothing unusual here; strange things like this were all too common along their route. Wasn’t the Catholic church 200 meters down the road just like this?

At 10:30 Yuan Gongchun, representing the Gongga Mountain Setting Sun Red Elderly People’s Club, read words of welcome to the Long March. At 11:00, the Elderly People’s Club members began performing for everyone. Their program had many parts, and many costumes had been lent by the Long March. It turned out that in addition to the rewritten revolutionary songs originally called for in the plan, Uncle Yuan had also arranged for some Tibetan dance, solo dance, fan dance, clapper ballads-in short, the group ran through all of the things they practiced on a daily basis. In the context created by the “Christianized” stage and the folk beliefs of Jinhua Temple, almost everything that happened took on special meaning. The Long Marchers were happy just to have come. As they heard the news, more and more villagers came to join in the hubbub, eventually filling the square.

At midday, the Elderly People’s Club set out a huge banquet for the Long March, with meat and fish, in just the way peasants would welcome a passing army into their homes.

At 14:30, the Elderly People’s Club organized almost a hundred people to do the Tibetan Guozhuang dance in front of the gate to the Catholic church where Mao is said to have stayed. Moxi is a town with residents of Tibetan, Qiang, Yi, and Han nationality, but people of every nationality know how to do the Tibetan Guozhuang dance. The music played from small speakers in front of the church entrance, and the people who heard the music and went to partake of the dance grew in number. There were several hundred dancers, including some in Tibetan dress and some in street clothes. They kept dancing; there were three layers of people inside and three outside, as festive as if the town were celebrating a holiday. The Long Marchers were extremely excited as they walked around pinning Long March stickers to every arm they could.

Shi Qing, The Flood, performance

To the north, on a site overlooking Jinhua Temple and the commotion in front of the Catholic church, Shi Qing directed the more than ten workers he had hired in the final preparations for his work The Great Flood. The Great Flood took its name from the story in the Bible, and Shi Qing had turned it into a massive and strange mix of installation, performance, and theater. The image of Noah’s Ark was exchanged by Shi Qing for a dock built on a high point in the town of Moxi. On the dock sat a tall tower that seemed to converse with the Catholic church’s steeple four hundred meters away. The performers were Shi Qing himself and five young Tibetan men, all wearing striped sailor’s shirts, waterproof goggles, and carrying transparent plastic air sacs on their backs. These were the modern tools that Shi Qing suggests we prepare in case of a flood. What Shi Qing was looking to save, besides a sheep resting atop the dock, seemed to be a boatload of maize.

On the second floor of the building, i.e. the lower floor of the dock, hung six bamboo cages. In each cage was held a dove, replacing the animals Noah endeavored to save in his ark. But they had been stashed beneath the dock, in a place where they would definitely be drowned.

At 17:00, Shi Qing’s performance began.

The performance atop the building ended, and moved toward the town. Six motorcycles had been waiting for some time beneath the building. The performers, wearing goggles, striped shirts, and air sacs hopped on the motorcycles, each one holding a bundle of cornstalks in hand. The sheep also boarded a motorcycle. The motorcycles roared into Moxi on a rampage, attracting the attention of the townspeople. People weren’t surprised though, as many strange things had happened in the last few days.

Lu Jie crouched on the back of a motorcycle, carrying three cameras, and changing a roll of film amidst the chaos. Shen Xiaomin’s video camera was easily ready for battle, and he filmed from the back of a motorcycle. Only the poor television crew, with their massive equipment, was forced to watch the action from afar.

Qiu Zhijie came along with the six Tibetan girls who had continuously been by his side, running quickly toward the church. They ran quickly in order to be able to shoot the motorcycles’ attack on the church square.

The caravan raced through the streets for fifteen minutes, rushing madly toward the Catholic church at 18:15, and running circles through the square. The air sacs and cornstalks rocked back and forth before everyone’s eyes. This was an important part of the performance: the charge on the church.

A moment later, the caravan stormed out of the square, and headed for the theater in front of Jinhua Temple.

Shi Qing led a group into the amphitheater, and climbed atop the stage that had been changed into a Christian space. This time, the six Tibetan girls were already waiting at the door of Jinhua Temple across the street.

The “divers” were still carrying cornstalks, and they filed out of the stage/Christian space, walked towards Jinhua Temple, and gave the cornstalks to the girls. These were the foodstuffs they had saved from the dock of The Great Flood, and they were to be given to later generations. The presentations were made in the traditional Tibetan manner. The entire atmosphere changed from the chaos of the motorcycle attack back into the solemnity of the ritual bath with which the performance began.

It was already dusk by this point, and a group of elderly people squatted by the temple entrance reading the Buddhist scriptures. This was their daily homework.

The Great Flood drew its heft from its vivid theatricality, and its intermingling of religious and folk symbols, and local and imported legends. It combined modern rescue equipment with a timeless sense of fear, mixing them together in a chaotic, confusing narrative. It was fictitious and realistic, experience and performance, theater and ritual.

There was not enough time to think this over in detail, as the next event was just about to begin. The sky was gradually getting dark, and this evening they would project the movie Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, Shi Qing’s CD-ROM Salvation and Apocalypse, Qiu Zhijie’s CD-ROM The West, and some materials about the Boxer Uprising. Because Uncle Yuan had publicized this with signs around town as an activity of the Elderly People’s Club, as soon as it grew dark, four or five hundred people arrived.

The two largest peasant uprisings in China during the 19th Century, the Taiping and Boxer rebellions, had to do with Christianity. The former claimed to stem from the egalitarian thought of Christian teachings, while the latter burned down churches with slogans of resistance to foreign beliefs. From the early cultural exchanges of the Tang Dynasty on, the transmission of Christianity in China proceeded slowly. In the late Ming, Matteo Ricci and others used natural sciences to attract Chinese intellectuals and began to convert on a large scale. This sort of missionary activity grew more intense as the “national door” swung open in the wake of the Opium Wars, penetrating to China’s innermost reaches, leading finally to the anti-religious “Brotherhood of the Heavenly Fists,” or Boxers. One could say that Christian transmission has been a deep influence on China’s modernization process. The problems faced by this set of foreign ideas when placed in the Chinese context form an interesting point of contrast with another set of imported ideas-Marxism.

This was the reason for screening this set of materials in Moxi. The gathered viewers in the Jinhua amphitheater eagerly debated with the Long Marchers, not leaving until after midnight. At this point, the Marchers, busy from a long day’s work, finally sat down to eat.