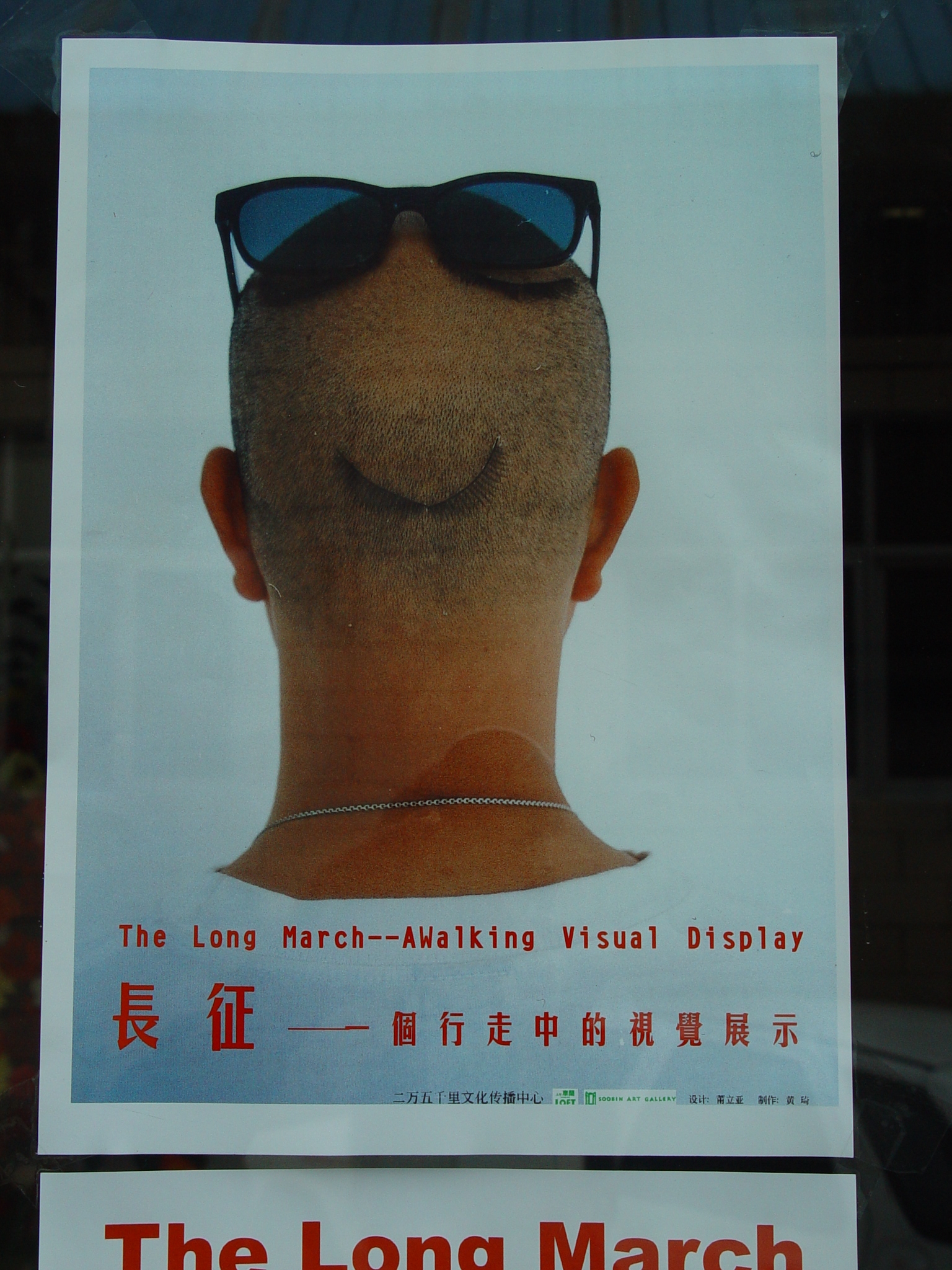

Long March – A Walking Visual Display

作品《难民共和国》展在原中华苏维埃中央临时政府前展出-2-400x300.jpg)

Site 1: Ruijin, Jiangxi Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Jun. 28 – Jul. 7, 2002

Site 2: Jinggangshan, Jiangxi Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Jul. 8 – Jul. 12, 2002

Site 3: Daozhong, Guangxi Autonomous Region

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Jul. 13 – Jul. 18, 2002

Site 4: Kunming, Yunnan Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Jul. 21 – Jul.22, Aug. 2 – Aug.5, 2002

Site 5: Lijiang, Yunnan Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Jul. 23 – Jul. 27, 2002

Jul. 31 –Aug.01,2002

Site 6: Lugu Lake, Yunnan/Sichuan Provinces

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Jul. 27 – Jul. 30, 2002

Site 7: On the Train between Kunming and Zunyi

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Aug. 6, 2002

Site 8: Zunyi, Guizhou Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Aug. 7 – Aug. 12, 2002

Site 9: Maotai, Guizhou Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Aug. 13 – Aug. 15, 2002

Site 10: Xichang Long March Satelite Station, Sichuan Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Aug. 16 – Aug. 21

Site 11: Moxi, Sichuan Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Aug. 22 – Aug. 27, 2002

Site 12: From Anshunchang to Luding Bridge

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Aug. 28 – Sep. 1, 2002

Works made along the Long March

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: 2002

Artists: Qu Guangci, Qiu Zhenzhong, Song Dong, Yin Xiuzhen, Wang Bo, Qin Ga, Qiu Zhijie, Ingo Günther, Jiang Jie, Wang Jingsong, Yao Ruizhong, Shao Yinong, Mu Chen, Xiao Lu, Shen Meng, Xiao Xiong, Ding Jie

Site 4: Kunming, Yunnan Province

Long March- A Walking Visual Display

Time: Jul. 21 – Jul.22, Aug. 2 – Aug.5, 2002

Curatorial Plan: Maoism and the mass line – China in Western textual imagination and narration from the 1970s and ‘80s until the present

Route:Kunming, Yunnan Province

Time: July 19 to July 22, August 2 to August 5

July 19 to July 22: Kunming

Fu Liya performed his work "Water Asking" at the Upriver Loft Gallery

The Long Marchers arrived in Kunming

"Indoctrination – Contemporary Art Exhibition" at Jiangwutang Military School

August 2 to August 5: Kunming

Installation in Luo Xu’s Native Nest

The Exhibition about an Exhibition at the Upriver Loft

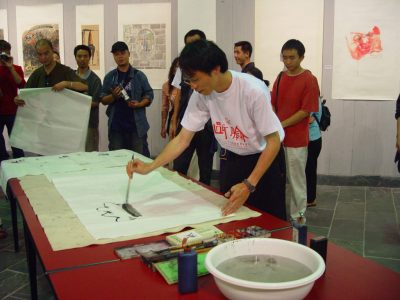

Collective collaboration to create ink painting at Nordica Art Gallery

Evening Screening at a local Yunnanese restaurant

Lugu Lake Artist Exhibition at the Museum of Yunnan Academy of Fine Arts

In recent years, Kunming’s artistic circle has been extraordinarily active. There is now an old factory on Xiba Road that is home to Jingpin Gallery, The Upriver Loft, The Nautica Center, and the studios of Pan Dehai and more than 30 other famous painters. Houxin Avenue is home to the Upriver Art Club, a multi-purpose club that includes a dormitory, studios, a café, and a small exhibition hall. These artistic facilities, combined with the new community of artists’ studios in Dali and the Muwangfu Post Station in Lijiang, constitute a group of resources that is widely shared, creating a strong artistic network. Moreover, these facilities have built friendly, cooperative relationships with local government and media. These artists have built a self-sufficient, though not isolated, artistic system outside the so-called “art centers” of Beijing and Shanghai. And due to the international experience and connections of leading figure Ye Yongqing, this Yunnan art network is fairly globalized.

Itinerary on July 18 was simply to return to Guilin.

That evening, it was discovered that the portable GPS reader needed for Ingo Gunther’s work had been left on the bus, so the group quickly gave a call back to Yangshuo to recover it. The manager of the hotel in Yangshuo, still earnestly distributing Long March postcards even after the group had moved on, took on a serve-the-people attitude and circled the city searching for the gadget.

July 19

Lu Jie flew to Kunming in advance of the group to take part in at the opening of the Upriver Loft The exhibition contained works by Liu Hong and Fu Liya.

Fu Liya performed his work "Water Asking" at the Upriver Loft Gallery

July 19

Qiu Zhijie and the ranks of the marchers boarded the train. Immediately prior to boarding, they recovered the GPS reader from a kind-hearted Yangshuo bus driver. Recovering the gadget, which stored data from the first three stops along the Long March, added a comic element to the journey, searching, and memory themes of the Guangxi stage of the exhibition.

“Qu Guangci” raised some concerns while trying to get his sculpture through the train station’s security checkpoint. His bag was opened and searched, and only after he explained that he was carrying the sculpture for a TV show was he able to clear the checkpoint.

American artist Judy Chicago and her husband Donald Woodman arrived in Beijing. Lisa Horikawa, Guo Yu, Xiao Liu, and Yang Tao got busy with the preparations for her coming lecture at The Loft.

That afternoon, the Long March occupied the Upriver Loft office of owner Ye Yongqing, turning it into a base of operations. A delegation from the Long March Foundation New York arrived, including Shen Meng, Lu Jie’s wife. She brought with her the latest results of the Long March Propaganda Team’s work in Xu Bing’s Brooklyn home-studio: a Long March logo designed by Xu Bing in his New English Calligraphy. The Propaganda Team members who helped with the logo included: Wang Gongxin and Lin Tianmiao, Shen Meng and her children, Cai Guoqiang’s wife Wu Honghong and daughter Cai Wenyou, Chen Zhen’s wife Xu Min, the biologist Yu Congrong, Ma Limei and others. Xu Bing also designed a special badge for the Long March, featuring a hammer, a sickle, and a calligraphy brush. Qiu Zhijie immediately got on his computer and used the new materials to design Long March T-shirts, flags, and stickers. He burnt these onto a CD and sent Ma Han to have them printed. In this way, the Long March gained a propaganda tool other than the original postcards, new materials that could be quickly distributed to passers-by. The working efficiency of the “Central Red Army” was enough to make observers faint in amazement.

Later in the afternoon, “Qu Guangci,” carrying his statue of Qu Guangci, paid visits one by one to the Upriver Loft studios of artists Duan Yuhai, Luan Xiaojie, Liu Jianhua, and Ye Yongqing, as well as the studio of visiting British artist Chris Jones.

Prior to the group’s arrival, Ye Yongqing had been in contact with Jiangwutang Military School about the use of their space.

All of the works exhibited there were installations having to do with the idea of the classroom, looking to interrogate the changes in both Chinese traditional education and the Western educational model, and thinking about reactions to the process of modernization.

The exhibition having been installed, the marchers moved to the Upriver Loft, where in the second floor display room they re-installed the Li Tianbing-Li Jincheng Father-Son Photography Exhibition from Ruijin, the Long March’s first site. This exhibition was re-installed because it pertained to questions the Long March wished to discuss about the situation of artists in Kunming.

When the Long March team arrived in Kunming, young British artists Chris Jones and Pauline Thomas were working in their studios at the Upriver Loft, and living in the Upriver Art Club. Their ongoing exhibition Right and Wrong, then taking place at the Upriver Loft, was included in an August 3 Long March exhibition.

In the afternoon of July 22, the Indoctrination exhibition opened at Jiangwutang Military School.

Xu Bing’s New English Calligraphy Long March stickers were laid out one by one on the windowsills. Viewers were encouraged to take the brushes and ink which had been prepared and try their hand at writing in this script. Shen Maotou, Long March Propaganda Team member and son of Shen Meng, had studied New English Calligraphy under Xu Bing in New York. He became a “little teacher” at Jiangwutang, teaching other children how to write the characters.

Displayed in the same room as Xu Bing’s New English Calligraphy was Wang Jinsong’s video work, One History Class of Mine. After sitting before the camera for ten minutes without expression, the artist begins to write one line on the blackboard: “An accomplished fact cannot be contested.”

In the second hall was Ma Han’s work White Shirt Drawing Seminar. Ma Han starched a set of eighteen white shirts, molding them to resemble bodiless statues. The shirts were hung in midair like flying birds, and a group of school children holding sketchbooks were seated underneath. Ma Han gave the kids an onsite lesson in charcoal drawing. After the sketching session was over, the shirts were distributed one per student as a “homework assignment.” Ma Han asked the students to draw directly on the shirts and return them to him as the third phase of this work.

After distributing the shirts, Ma Han led the assembled viewers in recreating a scene from a famous Cultural Revolution era print of a struggle session entitled Blood Clothing by Wang Shikuo. Ye Yongqing willingly played the part of the old landlord being criticized in the picture. Lu Jie, posing as chairman, answered questions from the film crew, introducing the notion of curating by talking about the meaning of spatial and historical context and artistic education. In this re-enactment “blood clothing” was replaced by a clean white shirt; the shift symbolized the end of the connection between art and change.

In the third hall were two old works, Zhang Peili’s classic video Standard Pronunciation-Water Cihai and Song Dong’s Another Class, Are You Willing to Play with Me?

In the fourth hall, He Chi worked on his Large Character Pinyin Teaching Materials. He Chi rewrote thirty of Mao Zedong’s poems using characters with the same pronunciation but different meanings from the originals, printing a set of posters to be hung in a classroom and a set of low-priced textbooks on cheap paper. A sunflower blossom was placed on each desk, and viewers sat on top of the blossoms, using the textbooks that lay open on the floor to follow He Chi in a guided reading of the poems. The children in the class had not previously studied Mao’s Poem “Seven Rules, One Long March,” so they were introduced to this history in an auditory experience with a set of identical sounds with variant meanings.

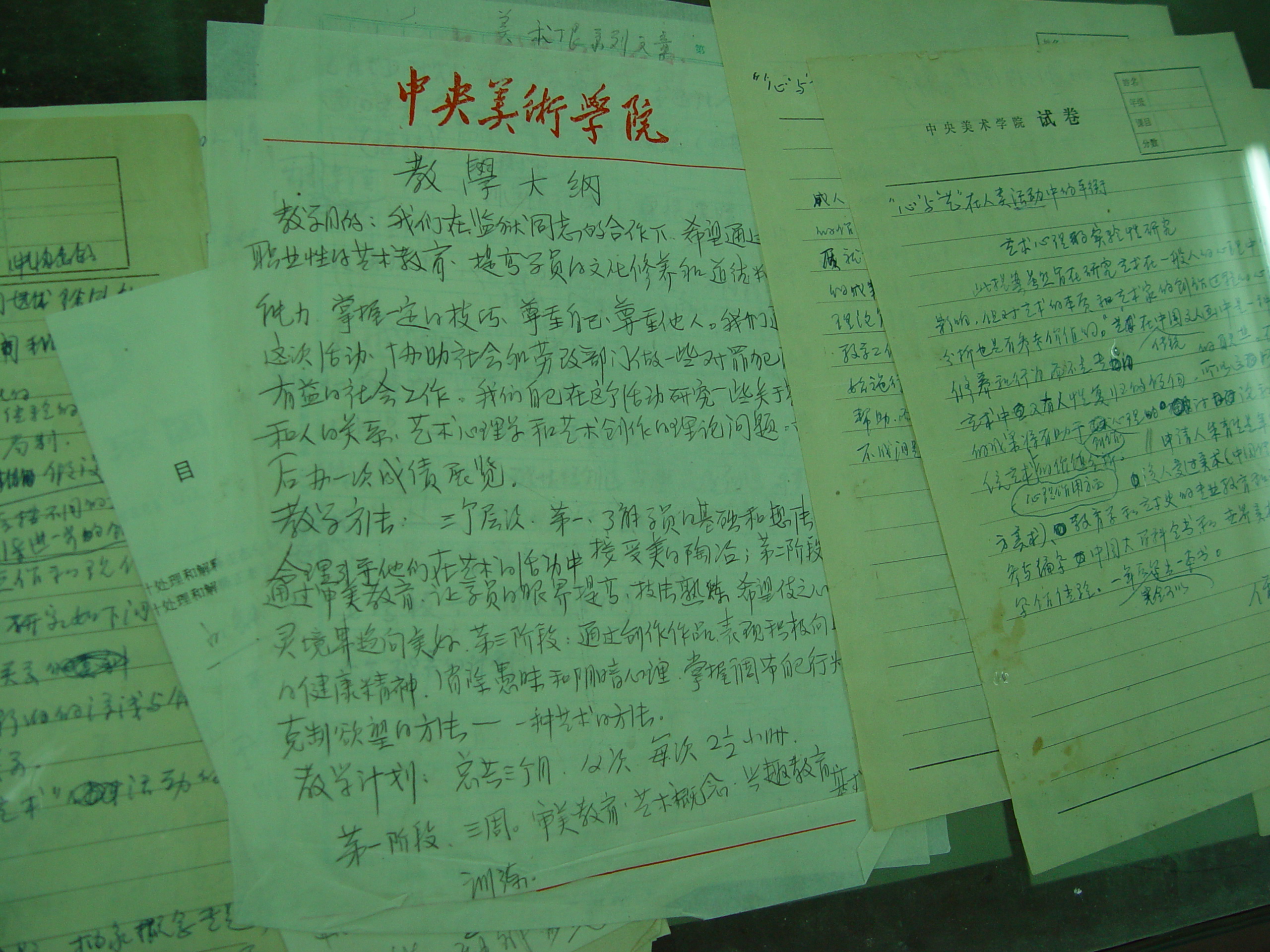

In the fifth hall, Zhu Qingsheng, Zhu Yan, Kong Chang’an, and Ding Binhe collaborated to produce the Prisoners’Ink Wash Works Cases series. These four artists realized this work long ago, in 1986, when they were graduate students at the Central Academy of Fine Arts. The work is conducted in a manner similar to a sociological survey. Ink washes are used as an educational tactic for Beijing prisoners. Different prisoners’ individual characteristics become visible on paper, bringing out the differences between amateurs and professionals, expressionists and aesthetes, regulated and divergent personalities. The exhibition included working photos, class outlines, and communications from Zhu Qingsheng and others. One handkerchief on which a prisoner had drawn a landscape scene was particularly able to attract the gaze of viewers.

This exhibition would continue at Jiangwutang Military School for one week.

That evening Lu Jie and Qiu Zhijie held a meeting at the Upriver Loft with the female artists who were to take part in the upcoming exhibition at Lugu Lake. They talked continuously of the substance and arrangement of the works to be exhibited.

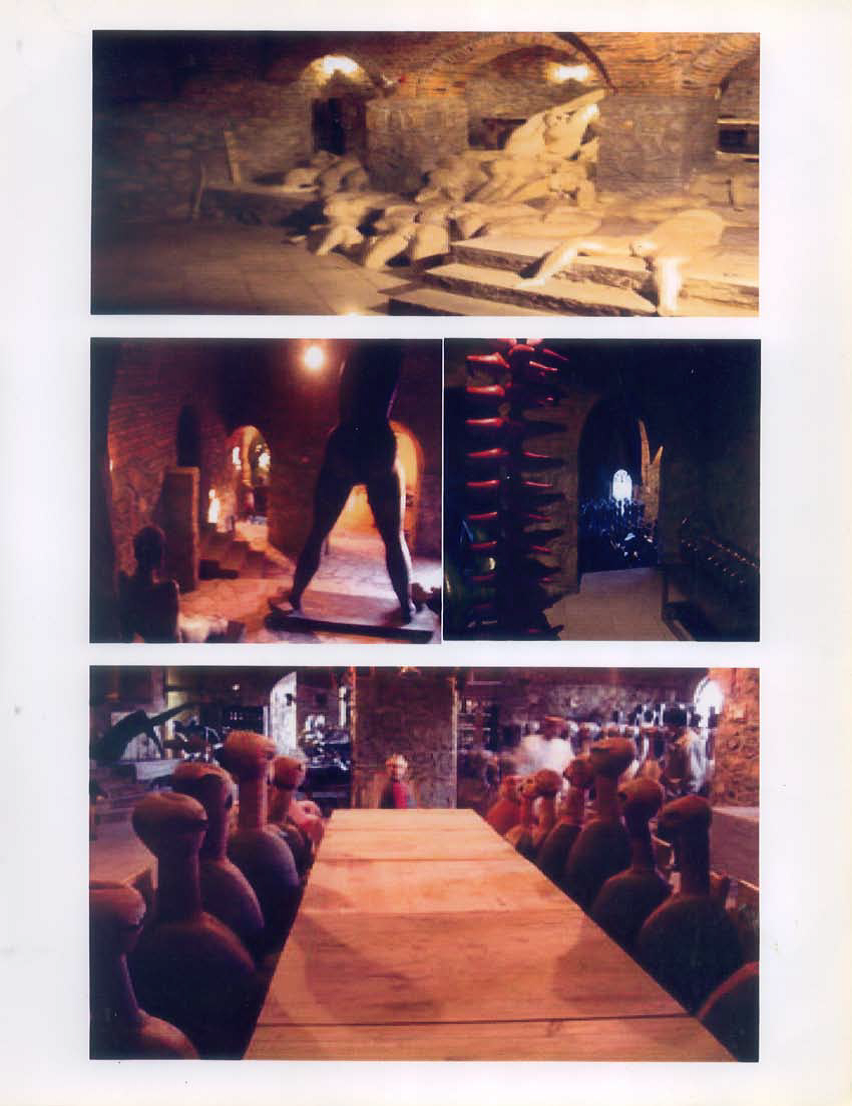

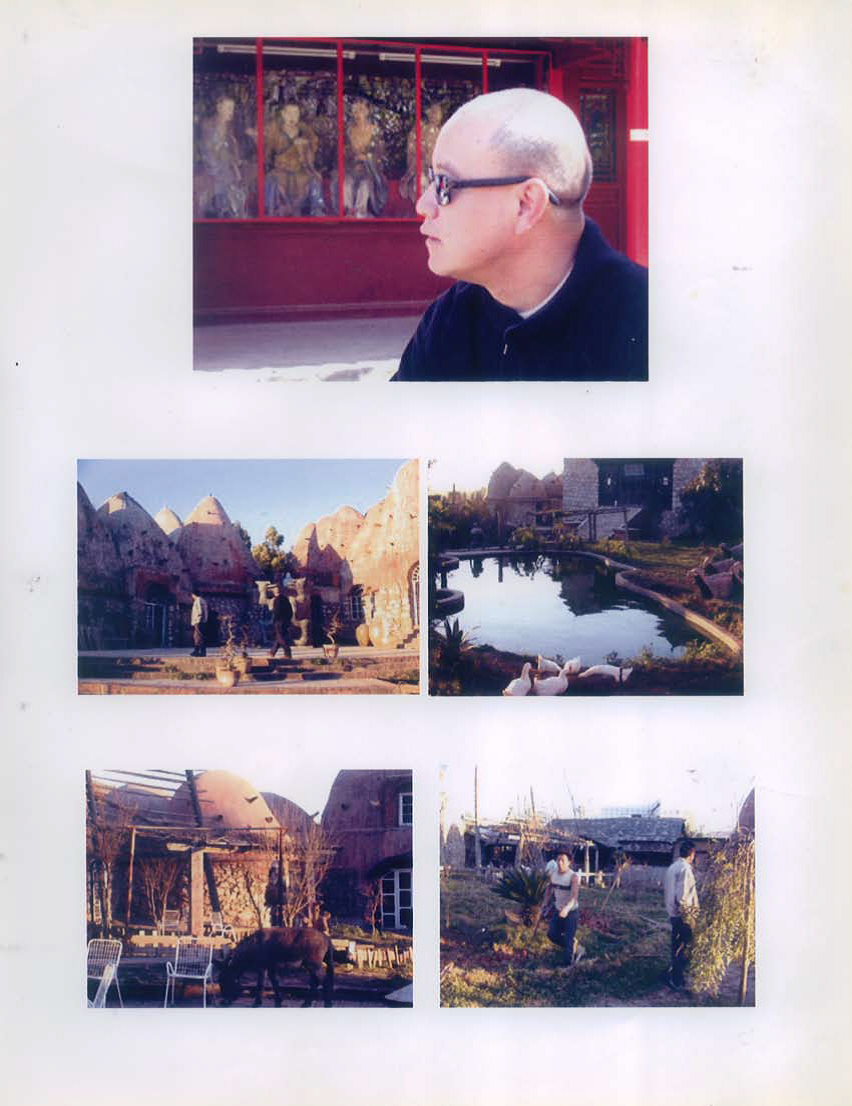

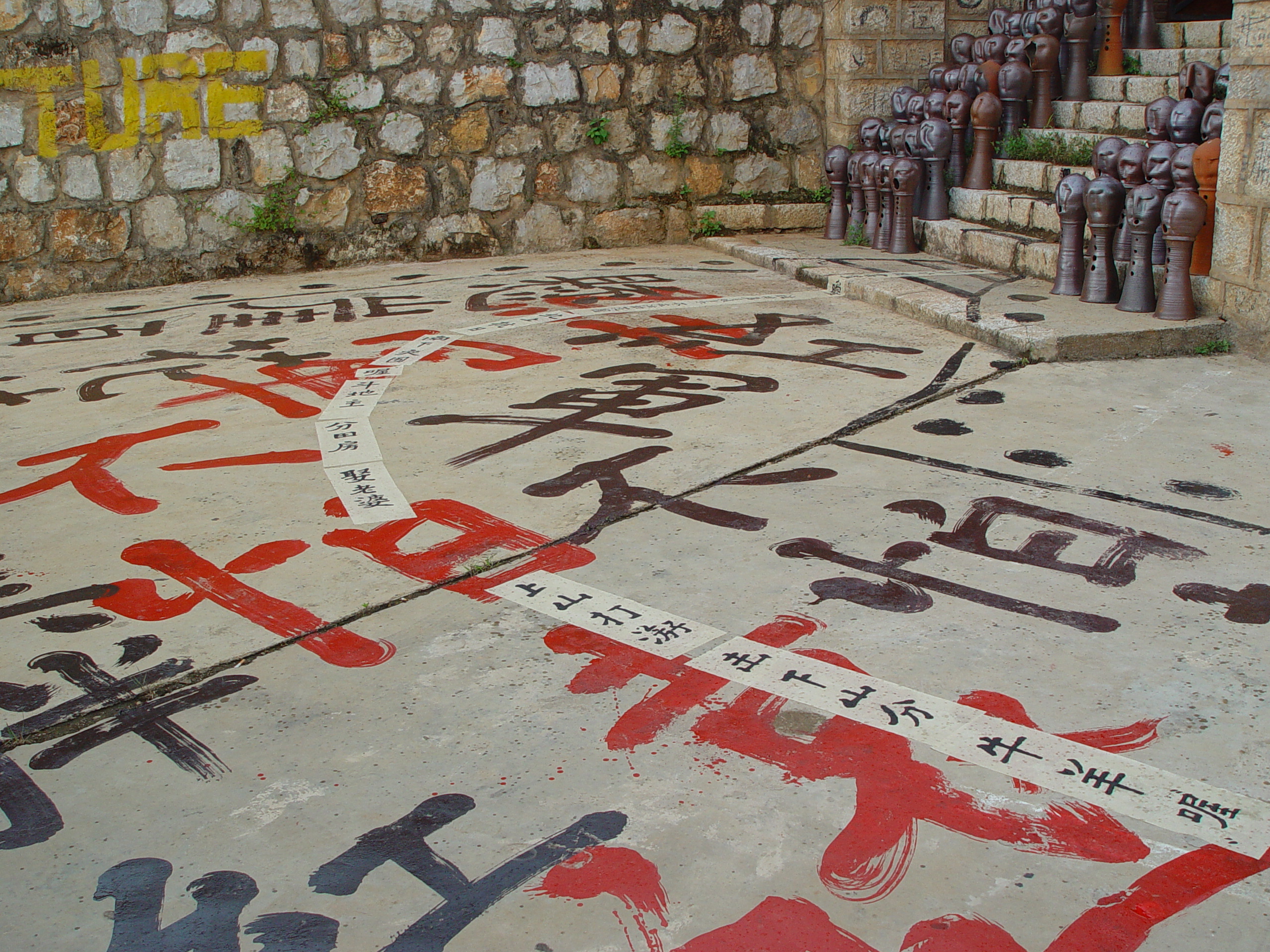

Luo Xu is a sculptor in the tradition of the Yi minority, who several years ago borrowed millions of RMB to build a sculpture garden on the outskirts of Kunming. Called a sculpture “nest,” this appellation accurately describes the character of the place; it was pieced together like a bird pieces together a nest. The rumor is that Luo first used white ash to paint a circle on this mountain slope, and then instructed the construction crew to build wherever he placed bamboo poles. Finally, multiple unsuccessful efforts led to an ideal structure, which looks like a loaf of steamed bread from outside, and appears from inside as if height, width, and depth have been set at random, creating the effect of a maze. The larger rooms mostly have domed ceilings, supported by girders in a cathedralesque manner. Light comes through skylights and holes set into the walls.

This piece of architecture, which has grown like a plant, has become a display hall for Luo Xu’s sculptures, in which works he has created over nearly twenty years in all imaginable sculptural styles are scattered into nearly every corner. The most conspicuous work in the place takes a thigh as its main element, and has an obvious air of life-worship to it, enhanced by and enhancing the arched ceiling, full of mystical power.

In the earlier process of investigating sites for the Long March, Lu Jie and Qiu Zhijie made a preliminary visit to Luo Xu, and were stirred by the combination of his sculptures and their environment, moved by the way in which this man creates like an ant-king. He made them think of the palace of found objects built by that harbinger of surrealism Ferdinand Cheval. This sort of artistic site could not be shipped off and exhibited in an art “center” like Venice, Kassel, Beijing, or Shanghai. To contact this work of art, one must come directly to the scene, must experience it firsthand. On this account, the Long March curators especially chose to hold here the sort of activity that is most dependent on firsthand experience-a sound installation exhibition. The special geographic situation and architectural layout of Luo Xu’s nest made it ideal for this sort of exhibition. The curators hoped to draw on both of these strengths, and to create value for the “site” out of the significance of the local culture and the physical location.

Works by Yu Xiaofeng, Ren Qian, and Ma Jie had already been installed, and interactive works by Li Chuan and Li Yong were still being installed. These five artists from Chongqing were also participants in China’s first true sound art exhibition, held one year ago at the Mustard Seed Garden in Beijing, members of China’s first generation of experimental sound artists. All are incredibly young, though their works grow more mature by the day.

The Exhibition about an Exhibition at the Upriver Loft

August 3

Exhibition about an Exhibition collected works by several popular Chinese easel painters, but arranged them according to a curatorial principal of circularity. In terms of works, this meant showing not the most well-known works, but works that showed the creative background, materials, and vestiges of the artists’ earlier works, looking more at the process behind their “finished products” than the products themselves. In terms of artist selection, this meant choosing artists with no prior connection to the Loft in Kunming.

For example, Zhang Xiaogang, who explores the contemporary soul of China in paintings that have the flare of old photographs, was represented in this exhibition by a series of actual photographs entitled Credentials.

Though the pictures in Credentials are all of the standard “passport photo” variety, what the installation reveals is the many masks a single person wears in relation to society. “Credentials” showed the multiplicity required by society’s many requirements of its members even as it exhibited relics of the destruction implicit in the processes of individual maturation and social change. The system of authority whereby existing power structures have the power to determine identity also exerts an untraceable influence on the artist, creating a sort of restructuring amidst all the disintegration. Credentials presents traces of Zhang Xiaogang’s personal career, and like his Big Family series of oil paintings, it ineffably faces the vicissitudes of the individual in relation to society.

During the activities in Sichuan, Ye Yongqing earned the title of “scout hero.” Every time Ye Yongqing, or General Ye as his friends call him, returns to China, those around him love to hear his stories about the world beyond. He has already filled five passports. These filled passports show him off not as a traveler, but as someone with a broad international vision, with a fine tuned plan for his own locality. He is an artist’s artist, and for that reason he created the Upriver Loft space in Kunming where the current exhibition was about to be held. His installation From Here to There was the story of himself and the Upriver Loft.

Pasted amidst this mosaic of international travel was Ye Yongqing’s personal artistic world, on the one hand linking with society’s timeworn dicta, on the other connecting to the opening of space and the advent of new activities.

In one corner of the Upriver Loft, a tape of an interview with painter Song Yonghong attracted attention. A computer on a table showed slides of daily life amongst the Beijing artists’ community: studios, kitchens, studios. It showed a system of personal relationships constantly in flux, a sort of common knowledge base, an excessively specialized system of identity, stratified along many different lines: age, place of origin, personality and experience, fame, money, even food preferences and artistic style.

Chengdu painter Yang Mian displayed a computer generated cartoon of an “ideal residential community,” sarcastically mixing his terror and worry over the “beautiful new world.” Kunming painter Zhang Zhongqi used a camera to record the lonely and quiet daily life of a former Red Army soldier.

Yang Shaobin’s photographs Friends were taken to assist him in creating oil paintings. The photos show people fighting viciously and friends of the artist. Yue Minjun’s video installation, on the other hand, did not initially resemble his paintings. It showed a visit to an elementary school in a poor mountain village, the lens repeatedly flashing in the students’ dirty faces, tattered clothing, and simple gazes. They reminded the viewer of the faces in Yue Minjun’s paintings, as the children’s grins and laughter looked wise and sagacious in the context of utter poverty.

Another wall of The Loft was filled with small works left by the international artists who had previously lived and worked in the space: Bao Li’s video Birds; Lisa’s material work Jewelry; and Takahashi Tomoko’s photomontage. The presentation of these works in combination with the open studio exhibitions taking place combined to present the history of The Loft over the past few years in a single exhibition.

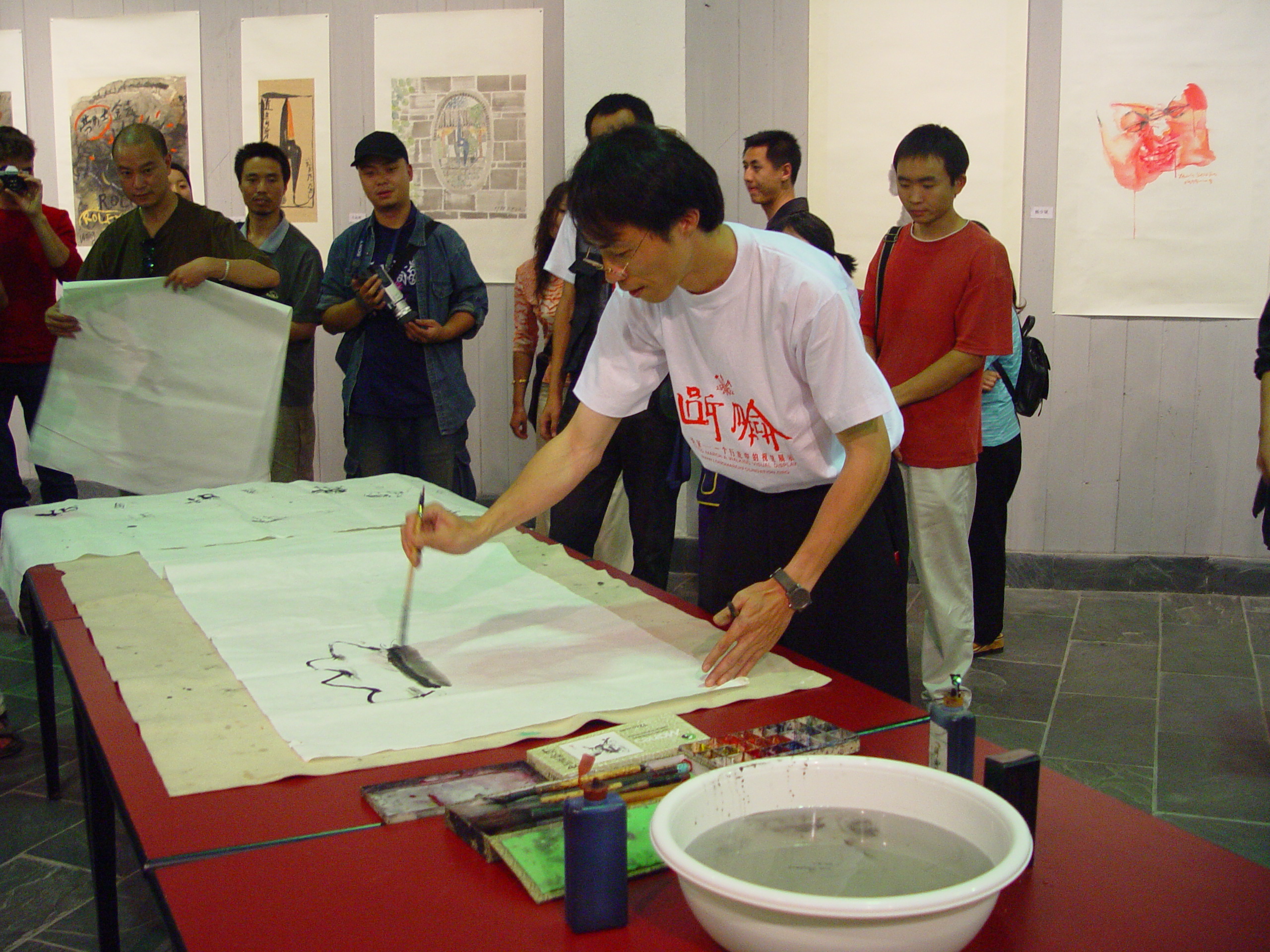

After the opening ceremony, people moved next door to Sweden’s Nordica Center to participate in another Long March activity: Degeneration: Works by the Dali Ink Painting Studio.

The Dali Ink Painting Studio was opened two years ago by Li Xianting and Ye Yongqing, and was funded by Soo Bin Chua of Singapore with the aim of creating a modern genre of ink painting. Zhang Xiaogang, Zhou Chunya, Mao Xuhui, Fang Lijun, Liu Wei, Wang Guangyi, Yue Minjun, and Yang Shaobin are some of the famous oil panters who have participated in the project, converging on Dali for a week of ink painting. These painters, all trained in the Western academic style, ran into the problem that the very materials of Chinese ink and wash painting raised their expectations, and creating in this sort of collective studio atmosphere caused the painters to reflect on their own education. They wondered whether the creation-display model was truly the only paradigm for artistic creation, whether other ways of playing the game existed, perhaps psychological frameworks that would incorporate local culture. Thinking about these questions, people came to appreciate the many works of alternative ink and wash painting on display at the Nordica Center. From beginning to end, the viewers looked to the works for traces of classic ink and wash, ever and again looking to the paintings for a connection with old styles, and feeling astonished at this break with tradition.

This “gathering of scholars” style of exchange made the curators of the Long March quite happy, and so, at 20:30 that evening, there began an ink painting session. Lu Jie, who began as a student of Chinese painting, painted a Red Army flag waving in the grasslands of a snowy mountain. Picking up where he left off, Zhang Xiaogang added the overcast eyes often seen in his paintings, and Yue Minjun, Mao Xuhui, and Cai Simin one by one took turns. This precious sheet of rice paper became invaluable, and after the painters had all added their contributions, Lu Jie’s son Maotou and Zhang Xiaogang’s daughter Huanhuan had a chance to paint.

Wang Gongxin’s Karaoke, from a technological perspective, was foremost a visual game.

This video actually invaded the mouth of one viewer. Intricate sound editing is a specialty of Wang Gongxin’s works, and the work was successful in that the loud screams lead to subconscious imitation.

Wu Ershan completed a work for a Jazz stage entitled Evolution Jazz, its screen filled with dizzying numbers and all sorts of scribbles. Accompanying this work was Chen Dili’s MiDi-produced music, which turned The Native’s Nest into a mysterious place.

Chen Xiaoyun’s Who is an Angel is a classic example of the inversion of sound and image. The image portrays people hopping in many different situations, but because the floor has been digitally removed from below them, they appear to be jumping in midair. The images were set to the sound of barking dogs, at once inexplicable and suggestive of a distant causal relationship.

Zhou Xiaohu’s Nursery Rhyme was another work about vocal transmission. Children standing in a circle repeat a sentence one to another; when the sentence is misheard, it gets repeated incorrectly, sometimes completely transforming in meaning.

These videos, from a psychological, physical, and social perspective reflected the important role which sound plays in contemporary art, providing a background for the several works of sound art which premiered at The Native’s Nest.

Moving in from the main hall, viewers were led into a deep maze by oil lamps in rough clay bowls. One dark room after another was hung with gloomy oil lamps, with an occasional scarecrow hung upside down in a corner. In the dark, ears could pick up the sounds of tiny bells from afar, and as one moved further in, the oil lamps became increasingly frequent, to the point where the viewer consciously avoided bumping into them. The noise of the bells also became clearer and clearer. Tiny star-like dots of light appeared in the distance. In the midst of this light and noise, the viewer suddenly felt a burst of hot air, like the breath of an animal. Borrowing on the subtle weakness of the oil lights, viewers discovered a bull nibbling on a scarecrow, with small bells hanging both from the scarecrow and the bull’s tail, producing noises in synch with the bull’s chewing. This work was by Ren Qian.

Compared with the scattered nature of Ren Qian’s work, Yu Xiaofeng’s Explosive Laughter seemed crazy and abrupt. In a round space, viewers saw a large round vat full of ink and mist, with a dozen or so small portable radios suspended above, emitting noisy, scrambled news broadcasts. The portable radios were hung by filament near several sticks of burning incense, so that each time a stick burned through to the head, it severed a filament, causing the radio to drop, splashing into the pot of ink. The sound of the splash ended the sound of the radio, and the space suddenly erupted into a moment of fantastic laughter. This was an “automatic” interactive sound work, its internal design having predicted this sort of movement and transition. Owing to the large quantity of incense and small tape recorders, as far as the viewers were concerned, this sort of movement was similarly unpredictable.

In other spaces of The Native’s Nest hang works by Li Yong, Li Chuan, and Ma Jie.

Li Yong’s work Entering the City, Leaving the City was the most turbulent of the entire exhibition. He whimsically drove three three-wheeled motorcycles into the space of the Native’s Nest, the sort of motorcycles with canopy covers very common on the far outskirts of Chinese cities. Such vehicles make a great deal of noise and emit much exhaust, are uncomfortable to sit upon, but are cheap and convenient-commonplace objects in a China on its way to wealth and happiness.

Everywhere was congested and awkward, moving forward or backward was equally difficult, and the roar of the vehicles filled the viewers’ ears. Movement was suppressed, and only the desire for movement manifested itself.

Moving from Li Yong’s work, viewers came to the work of Li Chuan. They walked through a hallway onto a red wooden path, embedded with a row of white footsteps. Stepping on these footprints, the space emitted sounds one by one. The dozen or so footprints formed one sentence: “Go forward along the road of socialism with Chinese characteristics.” Originally, sound equipment was connected below each footprint. As each footprint was stepped upon, it would emit the sound of a single character in the sentence. In reality, a person could traverse the hallway without stepping on each footprint, but viewers were intent on trying this. The white footprints were tempting in and of themselves, and attracted the participation of all present.

After passing through Li Chuan’s hallway, people entered a room decorated like a conference hall. Exactly in the center was a massive table, covered in a white tablecloth. One large grass shoe in the style of those worn by the Red Army, though two meters long, hung above the table, shaking left and right. The shoe’s mate was tiny in comparison, the size of an actual grass shoe. The small shoe was installed atop an electric toy that moved chaotically back and forth atop the table. The exhibit used a red string to connect the two shoes. The small mobile shoe controlled the movement of the hanging large shoe, but the red thread still controlled its range of motion, and the large shoe, swinging back and forth, influenced the movement of the small shoe. The two shoes moved in awkward but interactive relation, an illustration of Karl Popper’s idea of “situational logic.” The shadow of the large shoe covered the tablecloth, and the electric car with the small shoe was in its shadow. A brush had been affixed to the back of the toy car, and the car had been filled with colored dye, so that when the car moved, it left traces behind on the table, like blood marks. Because the relationship between the movement of the large and small shoes was mutually causal, the final form of the traces left behind on the table could not have been predicted, a sort of authorless abstract painting. The coloring ranged from dry to wet and light to dark, the result of artist Ma Jie constantly adding new dye, leaving dilemmatic traces of the vehicle’s presence.

Encounter with “influence” and “anxiety” as core narrative principles: this was the common point among the several sound works exhibited at The Native’s Nest. These influences and anxieties were sometimes as concrete as a red line or an electric cord, and other times hidden as an auditory temptation. In these works, no movement was automatic, and the forms of influence were many, including Long March itself as a catalyst for a sort of “red memory.” Other times the influence was a certain kind of ideological discourse, and yet others it was a local experience. Sometimes it was a specific technology expressed as a component of space.

Having come to appreciate several of the new sound works on display, the viewers came to realize that sound is perhaps only a pretext-the more important concepts of movement and site.

When people returned to the main hall of The Native’s Nest, it suddenly began to rain heavily, and water leaked in through holes in the roof, dripping on the projectors and computers, destroying everyone’s blind faith in the architecture of the building. The sound works were exhibited amidst claps of thunder in a sort of interplay between man and nature.

The original plan for the evening was to move several kilometers to Cuotuo Village and hold a screening of Jiang Zhi’s documentary work Shi Zhi.

Cuotuo Village became famous in the 1980s after the movie Cuotuo Years, which reflected the situation of young intellectuals in the post-Cultural Revolution period. Today, the village is a sea of Karaoke bars decorated with Roman columns and “peasant” restaurants. Many young intellectuals have become wealthy businessmen, and the town has become a place where they come to remember the spirit of their youth and spend money. Jiang Zhi’s documentary depicts the life of Shi Zhi, a representative of the young intellectual poets. Shi Zhi’s poems were once circulated among young intellectuals around the country, and the poem “Believe the Future” consoled countless hurt and hopeless youth during the Cuotuo years. Shi Zhi became hopeful owing to his poems, though his body was destroyed by his ideology, and to this day he remains in a mental institution in Beijing, writing his life story. The curators were thrilled to be bringing a documentary about Shi Zhi straight to Cuotuo Village.

After a few phone calls, the curators learned that because of heavy rains and road repairs, the road to Cuotuo Village was no longer passable. After much deliberation, Lu Jie and Qiu Zhijie decided to change their plan, return to Kunming, and show the documentary there in a young intellectuals’ restaurant. There was a massive Mao statue in the restaurant, and the documentary was projected just below it.

Lugu Lake Artist Exhibition at the Museum of Yunnan Academy of Fine Arts

August 5

The ten-plus artists who would exhibit at Lugu Lake continued their preparations, with the support of the Yunnan Academy of Fine Arts. This exhibition was organized proactively by participants of the Long March, without effort from the curators (who were of course happy to see something like this take place that would broaden the scope of the Long March). Objectively speaking, it was yet another example of the positive art atmosphere prevalent in Kunming.

The museum of the Yunnan Academy of Fine Arts very openly accepted all of the proposals by female artists at Lugu Lake, and in a few short days, installed a very informative documentary exhibition. To call it a documentary exhibition, however, is not entirely accurate, as things like Judy Chicago’s prayer flags were exhibited directly in the museum after being shown in Qidi Shanzhuang, and Sun Guojuan’s installation of cotton candy was moved from the Mosuo people’s vicinity to the exhibition site. The context of a matriarchal society, it seemed, had disappeared only physically; it would exist throughout conceptually. These works would be seen as re-manifestations of the original works. The richness and vitality of the exhibition had people thinking about the potential of an eventual comprehensive exhibition about the Long March project.

Liu Hong came to Lugu Lake as an observer, a friend of artists Fu Liya and others. This bystander raised an interesting question: during each of the performance works realized at Lugu Lake, video and still camera lenses were present. Would performance art fundamentally change in nature, lose its natural quality, owing to the presence of the lens? But if there was not a good record, performance could not be transmitted beyond its initial site. In the information age, is the value of unrecorded performance underrated? Liu Hong took a series of photographs relevant to this question. Her photos took up a series of questions faced also by the curators, and while her stance may have been oppositional, in the curators’ eyes, she brought to the fore a set of unavoidable questions about the internal contradictions of the contemporary art system, and revealed tensions among the notions of happening, first-hand experience, and performance which underlay the debate. Therefore, the curators gladly provided Liu Hong with many images to use as “fodder.”

At three that afternoon, the exhibition opened, and after introducing the artists, Lu Jie gave a speech of thanks to local Kunming artists for their support of the Long March project. Fu Liya read aloud a letter left by Judy Chicago, who had already returned to the U.S. The soft sculpture of Qu Guangci sat quietly in the front row through it all. Returning to Kunming, the Long Marchers thought about all that had happened in Lugu Lake with depth and serenity, thinking that the meaning of the Long March had more clearly expressed itself in the space between the works, and that it had made a pleasant atmosphere come over the group.

Curatorial Plan: Maoism and the mass line – China in Western textual imagination and narration from the 1970s and ‘80s until the present

Route:Kunming, Yunnan Province

Time: July 19 to July 22, August 2 to August 5

July 19 to July 22: Kunming

Fu Liya performed his work "Water Asking" at the Upriver Loft Gallery

The Long Marchers arrived in Kunming

"Indoctrination – Contemporary Art Exhibition" at Jiangwutang Military School

August 2 to August 5: Kunming

Installation in Luo Xu’s Native Nest

The Exhibition about an Exhibition at the Upriver Loft

Collective collaboration to create ink painting at Nordica Art Gallery

Evening Screening at a local Yunnanese restaurant

Lugu Lake Artist Exhibition at the Museum of Yunnan Academy of Fine Arts

In recent years, Kunming’s artistic circle has been extraordinarily active. There is now an old factory on Xiba Road that is home to Jingpin Gallery, The Upriver Loft, The Nautica Center, and the studios of Pan Dehai and more than 30 other famous painters. Houxin Avenue is home to the Upriver Art Club, a multi-purpose club that includes a dormitory, studios, a café, and a small exhibition hall. These artistic facilities, combined with the new community of artists’ studios in Dali and the Muwangfu Post Station in Lijiang, constitute a group of resources that is widely shared, creating a strong artistic network. Moreover, these facilities have built friendly, cooperative relationships with local government and media. These artists have built a self-sufficient, though not isolated, artistic system outside the so-called “art centers” of Beijing and Shanghai. And due to the international experience and connections of leading figure Ye Yongqing, this Yunnan art network is fairly globalized.

Itinerary on July 18 was simply to return to Guilin.

That evening, it was discovered that the portable GPS reader needed for Ingo Gunther’s work had been left on the bus, so the group quickly gave a call back to Yangshuo to recover it. The manager of the hotel in Yangshuo, still earnestly distributing Long March postcards even after the group had moved on, took on a serve-the-people attitude and circled the city searching for the gadget.

July 19

Lu Jie flew to Kunming in advance of the group to take part in at the opening of the Upriver Loft The exhibition contained works by Liu Hong and Fu Liya.